92022 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 52 ELR 10727

AGRICULTURAL EXCEPTIONALISM,

ENVIRONMENTAL INJUSTICE, AND

U.S. RIGHTTOFARM LAWS

by Danielle Diamond, Loka Ashwood, Allen Franco,

Lindsay Kuehn, Aimee Imlay, and Crystal Boutwell

Danielle Diamond is a visiting fellow with the Brooks McCormick Jr. Animal Law & Policy Program

at Harvard Law School. Loka Ashwood is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology at

the University of Kentucky. Allen Franco has a J.D. and an LL.M. in agriculture and food law from the

University of Arkansas, and is an assistant federal public defender with the Arkansas Capital Habeas

Unit. Lindsay Kuehn is a former pig farmer, now a staff attorney with the Farmers’ Legal Action Group.

Aimee Imlay is a sociology Ph.D. candidate at the University of Kentucky. Crystal Boutwell has a

master’s degree in rural sociology and a bachelor’s degree in natural resources management.

I

ndustrialized agriculture and its contribution to cli-

mate change and a host of other environmental and

public health problems have received more attention

in recent years. Many such accounts consider the law a

regulatory tool that counters environmental injustice—for

example, through the Clean Air Act (CAA)

1

and the Clean

Water Act (CWA).

2

Less focus has been a orded to how

the law enables environmental injustices through statutory

mandates that enable the most egregious industrial prac-

tices. While rural scholars and environmental policy advo-

1. 42 U.S.C. §§7401-7671q, ELR S. CAA §§101-618.

2. 33 U.S.C. §§1251-1387, ELR S. FWPCA §§101-607.

cates have increasingly recognized industrial agriculture

as a central agent of rural environmental injustice,

3

few

have considered how laws shape environmental injustices

in rural areas.

4

is may be because laws and policies are

often seen as solutions to, rather than potential drivers of,

environmental injustices.

5

Right-to-farm laws (RTFLs) exist at the interface of regu-

lation, common law, and corporate power, with remarkable

but underrecognized consequences for rural environmental

justice. Legislatures passed RTFLs with the stated intent of

protecting farmland and agriculture by limiting nuisance

suits against agricultural operations.

3. See Kaitlin Kelly-Reif & Steve Wing, Urban-Rural Exploitation: An Under-

appreciated Dimension of Environmental Injustice, 47 J. R S. 350

(2016); E. Paul Durrenberger & Kendall M. u, e Expansion of Large-

Scale Hog Farming in Iowa: e Applicability of Goldschmidt’s Findings Fifty

Years Later, 55 H. O. 409 (1996); Kelley J. Donham et al., Commu-

nity Health and Socioeconomic Issues Surrounding Concentrated Animal Feed-

ing Operations, 115 E’ H P. 317 (2007).

4. Kelly-Reif & Wing, supra note 3.

5. See, e.g., J L H, P D P

E J (2011).

Authors’ Note: The authors wish to thank the Brooks Mc-

Cormick Jr. Animal Law & Policy Program at Harvard Law

School for hosting the lead author (Danielle Diamond)

while completing this Article. Acknowledgment must also

be given to the many partners, farmers, and rural residents

who provided the inspiration for this Article. A portion of

the research was funded by the U.S. Department of Agri-

culture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Grant

No. 2018-68006-36699) with co-investigator the Farm-

ers’ Legal Action Group.

S U M M A R Y

SUMMARY

While the environmental justice movement has gained traction in the United States, the relationship between

agri-food systems and environmental injustices in rural areas has yet to come into focus. This Article explores

the relationship between U.S. agricultural exceptionalism and rural environmental justice through examining

right-to-farm laws. It demonstrates that the justifi cation for these statutes, protecting farmers from nuisance

suits, in practice transfers power from rural communities to industrial agriculture by safeguarding agribusi-

ness interests and certain types of production from lawsuits and liability. It considers how the original impetus

behind agricultural exceptionalism—to safeguard the food system through distributed and vibrant farms—

can be reconciled with environmental justice by repealing right-to-farm laws.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

52 ELR 10728 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 92022

Building on prior research,

6

this Article analyzes the

history of RTFLs and details how these laws have played

out in the courts. e Article also considers how agricul-

tural exceptionalism creates environmental injustices by

providing the impetus for repealing common-law private-

property rights and permitting agriculture operations to

operate outside environmental regulations. Our research

demonstrates that RTFLs have tipped the balance of jus-

tice between competing property interests in favor of envi-

ronmental degradation, by imposing one-sided protections

for large-scale industrial polluters—demonstrating a fail-

ure of RTFLs to serve their fundamental purpose.

I. Background

Historically, common-law nuisance actions provided an

avenue for rural landowners to defend their land, liveli-

hoods, health, quality of life, and the environment from

neighboring incompatible land uses.

7

However, in response

to concerns over suburban expansion into farmland areas

in the 1970s and 1980s,

8

state legislatures adopted the

political narrative that nuisance lawsuits brought by sub-

urban transplants posed a threat to agricultural resources.

9

Every state has enacted some form of an RTFL—thereby

solidifying the policy judgment that the social bene ts of

retaining agricultural land and protecting farming were so

great that “the balance between agriculture and other uses

should always be tipped toward agriculture.”

10

e notion that farm life and food production require

special protections is often referred to as “agricultural

exceptionalism,” and traces its origins back to Je ersonian

notions of a well-distributed and agrarian food system.

Based on this belief, farming and agriculture have his-

torically been a orded special protections and exemptions

from laws and regulations.

11

Indeed, agricultural excep-

tionalism has been infused into the national consciousness

since the early periods of Euro-American history, where

the welfare of agriculture was seen as “synonymous with

6. Loka Ashwood et al., Property Rights and Rural Justice: A Study of U.S. Right-

to-Farm Laws, 67 J. R S. 120 (2019).

7. Some say one of the rst environmental cases was an English common-law

nuisance case from the 1600s, when an action was brought by a property

owner against a neighboring hog sty. William Aldred Case (1611) 77 Eng.

Rep. 816, cited in H. Marlow Green, Common Law, Property Rights, and

the Environment: A Comparative Analysis of Historical Developments in the

United States and England and a Model for the Future, 30 C I’ L.J.

541 (1997).

8. By the 1970s, the United States was experiencing not only an acceleration of

suburban migration, but also the suburban encroachment onto land tradi-

tionally used for farming. Nearly 40% of the homes built between 1970 and

1979 were erected on large lots in rural areas. See N A

L S: F R 35, at 4 (1981).

9. See Jacqueline P. Hand, Right-to-Farm Laws: Breaking New Ground in the

Preservation of Farmland, 45 U. P. L. R. 289, 291 (1984).

10. Id.

11. Charlotte E. Blattner & Odile Ammann, Agricultural Exceptionalism and

Industrial Animal Food Production: Exploring the Human Rights Nexus, 15 J.

F L. P’ 92, 102 (2020) (noting that agricultural exceptionalism

removes farming “from the purview of the public, including in the areas of

environmental law, animal law, and property law ... trade law, employment

law, and many other areas”).

national well-being.”

12

Consequently, this resulted in sig-

ni cant government-sanctioned nancial bene ts and legal

protection for the agriculture sector,

13

which now receives

public entitlements to promote its economic standing

through various institutions.

14

Agricultural exceptionalism, while notable in its origi-

nal distributive tendencies, also derives from colonial set-

tlements that dispossessed indigenous people. ese old

patterns of white agrarianism carry over today into spe-

cial agricultural exemptions for large, corporate farms that

impose structural racism through the disenfranchisement

of farm laborers.

15

ere is a network of exceptions “from

social, labor, health, and safety legislation [that have] ...

reinforced agriculture’s unique status in law and society.”

erefore, agricultural exceptionalism has legitimized the

special treatment of the farm sector consecutively with the

inequitable and unequal treatment of farmworkers.

16

e U.S. government has played a crucial role in the

industrialization and corporatization of agriculture. Fed-

eral farm policy opened up access to new sources of credit

for farming operations, incentivized mass production

and e ciency, and generally ushered in the “Get Big or

Get Out!” era in farming. is movement allowed pow-

erful business corporations to accumulate capital and

resources, including land rights and food security, for the

bene t of a select few, while compromising the ability of

others to achieve the same.

17

A national farm crisis in the

1980s further perpetuated the loss of small to medium

sized farms as interest rates soared and commodity prices

collapsed.

18

is movement allowed for more vertical inte-

gration in the food and agriculture sectors and led to more

concentrated and intensive agricultural production.

19

e

development of RTFL protections coincided with this

increased market consolidation and intensi ed industrial

agriculture production.

20

12. See Guadalupe T. Luna, An In nite Distance?: Agricultural Exceptionalism

and Agricultural Labor, 1 U. P. J. L. E. L. 487, 490 (1998).

13. See id. (citing Jim Chen, e American Ideology, 48 V. L. R. 809, 818

(1995)).

14. Id. In this context, special exemptions have imposed a form of structural

racism on farm laborers.

15. Id.

16. See id. at 489 (citing E G, M L: T

M B S 106 (1964) (“[e]xemptions from federal leg-

islation provided to the agricultural sector comprise the doctrine of ag-

ricultural exceptionalism”); also referring to Carey McWilliams’ “Great

Exception” model, wherein agribusiness is exempt from “the basic tenets

of free enterprise”).

17. Philip McMichael, Peasant Prospects in the Neoliberal Age, 11 N P.

E. 407 (2006) (“It is this neoliberal trajectory of global capital accumu-

lation ... [t]he corporate food regime, which deepens the use, misuse and

abandonment of natural and social resources....”).

18. Garret Graddy-Lovelace, U.S. Farm Policy as Fraught Populism: Tracing the

Scalar Tensions of Nationalist Agricultural Governance, 109 A A.

A’ G 395 (2019); see also Martin B. King, Interpreting the

Consequences of Midwestern Agricultural Industrialization, 34 J. E. I-

425 (2000).

19. Jennifer Clapp & S. Ryan Isakson, Risky Returns: e Implications of Fi-

nancialization in the Food System, 49 D. C 437 (2018); see also

Sarah J. Martin & Jennifer Clapp, Finance for Agriculture or Agriculture for

Finance?, 15 J. A C 549 (2015).

20. Industrial agriculture is often characterized by large-scale operations with

unclear ownership and labor structures that utilize capital-intensive fossil

fuel-based technology in place of people and o -site corporate involvement

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

92022 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 52 ELR 10729

In the wake of the North American Free Trade Agree-

ment, the market advantage for pro t accumulation in

fewer and more transnational hands led to the decline

of other types of industrial manufacturing jobs in the

1990s.

21

At the same time, with the advent of the Internet

in 1990, 200 million people in 184 countries worldwide

recognized Earth Day.

22

In 1994, President Bill Clin-

ton issued an Executive Order directing federal actions

to address environmental justice in minority and low-

income populations.

23

is spurred a series of state and

federal regulations and policy initiatives, based on the rec-

ognition that low-income and communities of color bear

a disproportionate burden of environmental pollution and

associated health e ects.

24

Behind the smokescreen of U.S. agricultural excep-

tionalism, rural areas have increasingly been subjected to

“distributive injustices.”

25

Over time, public decisionmak-

ers have “traded rural welfare for some perceived collective

bene t.”

26

Social space—notably rural areas—are only now

beginning to receive scholarly recognition as an explicit

dimension of environmental injustice.

27

However, the gov-

ernment has made no such acknowledgment. For exam-

ple, the Code of Federal Regulations requires that nuclear

power plants only be sited in rural areas, in e ect enforc-

ing the utilitarian principle that the fewest must bear the

riskiest and most hazardous industries.

28

e same ideology

shapes federal regulations and agencies’ cost-bene t analy-

ses, wherein treating the rural equal to the urban rarely

happens because—under such logic—the costs outweigh

the bene ts.

29

driven by pro t interests. Production, distribution, and marketing systems

are vertically integrated into specialized business ventures controlled by a

few key players, like large corporate entities such as Smith eld, Tyson, and

Cargill. John M. Morrison, e Poultry Industry: A View of the Swine Indus-

try’s Future?, in P, P, R C 145 (Kendall M.

u & E. Paul Durrenberger eds., State Univ. of New York Press 1998).

21. Id.

22. Id. See National Archives—Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Mu-

seum, Earth Day, https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/news/earth-day (last visited

July 8, 2022).

23. See Exec. Order No. 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Jus-

tice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, 59 Fed. Reg.

7629 (Feb. 16, 1994), available at https://www.archives.gov/ les/federal-

register/executive-orders/pdf/12898.pdf.

24. J L H, F I O: T F E-

J W G A (2019).

25. Ann M. Eisenberg, Distributive Justice and Rural America, 61 B.C. L. R.

189, 195 (2020), available at https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/view-

content.cgi?article=3816&context=bclr.

26. Id.

27. Loka Ashwood & Kate MacTavish, Tyranny of the Majority and Rural Envi-

ronmental Injustice, 47 J. R S. 271 (2016).

28. Another example that shows how rural areas are left out of federal environ-

mental regulation is the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 (SDWA), Pub.

L. No. 93-523, 88 Stat. 1660 (codi ed at 42 U.S.C. §§300f to 300j-26).

is is the primary federal law that regulates groundwater and drinking

water pollution. e Act generally only applies to community water sup-

plies or “public water systems,” which leaves sparsely populated rural areas

where many farmers and residents rely on private water wells unprotected.

e SDWA de nes “public water system” generally to mean “a system for

the provision to the public of water for human consumption through pipes

or other constructed conveyances, if such system has at least fteen service

connections or regularly serves at least twenty- ve individuals.” 42 U.S.C.

§300f(4)(A).

29. See Eisenberg, supra note 25.

Industrial livestock production facilities, often referred

to as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs),

30

emblematize some of the most egregious outcomes of

industrial agriculture. CAFOs can con ne thousands and

sometimes millions of animals within buildings or enclosed

feedlots. e amount of waste produced at one site often

exceeds most small cities in the United States. Animals

raised for industrialized production are not a orded large

enough parcels of land to absorb waste, as would those

raised on smaller and diversi ed pasture-based farms.

31

Instead, the vast amounts of concentrated pollutants pro-

duced are often amassed in “lagoons” or waste pits, which

pose groundwater and surface water contamination risks

through leakage, runo , and so on.

Indeed, CAFO waste contains concentrated levels of

nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, and heavy

metals, pathogens, hormones, antibiotics, and ammonia,

among other pollutants.

32

Moreover, massive volumes of

urine and manure, often liqui ed for easier handling, pro-

duce gaseous pollutants such as ammonia, methane, and

hydrogen sul de, among others.

33

Air and water pollutants

also inevitably escape the boundaries of the facilities, which

leads to various environmental problems and impacts the

quality of life for people living nearby.

34

CAFOs have long been known to be one of the leading

sources of surface water pollution in the United States, and

to emit greenhouse gases that signi cantly contribute to

climate change.

35

Consistent with the ideals of agricultural

exceptionalism, CAFOs have largely escaped regulatory

30. e term “concentrated animal feeding operation,” or CAFO, rst ap-

peared in the original federal CWA of 1972 under the de nition of a “point

source.” e CWA speci cally de nes the term “point source” to include

CAFOs (33 U.S.C. §1362(14)).

31. Animal feeding operations (AFOs) are agricultural operations where ani-

mals are kept and raised in con ned situations. An “AFO” is de ned by the

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as

a lot or facility (other than an aquatic animal production facility)

where the following conditions are met: animals have been, are, or

will be stabled or con ned and fed or maintained for a total of 45

days or more in any 12-month period, and crops, vegetation, for-

age growth, or post-harvest residues are not sustained in the normal

growing season over any portion of the lot or facility.

See regulatory de nition at U.S. EPA, Animal Feeding Operations (AFOs),

https://www.epa.gov/npdes/animal-feeding-operations-afos (last updated

July 5, 2022). To be de ned as a “CAFO,” an AFO must meet a certain size

threshold depending on the type of animal con ned and/or the characteris-

tics of its waste treatment facilities.

32. U.S. EPA, E I A F O

(1998).

33. C H, N A L B H,

U C A F O

T I C (2010), https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/

docs/understanding_cafos_nalboh.pdf.

34. Id. See also Susan Bullers, Environmental Stressors, Perceived Control, and

Health: e Case of Residents Near Large-Scale Hog Farms in Eastern North

Carolina, 33 H. E 1 (2005); Susan S. Schi man et al., e E ect

of Environmental Odors Emanating From Commercial Swine Operations on

the Mood of Nearby Residents, 37 B R. B. 369 (1995).

35. See U.S. G A O (GAO), C

A F O: EPA N M I

C D S P A W Q F

P C (2008) (GAO-08-944), http://www.gao.gov/

new.items/d08944.pdf [hereinafter GAO R]; see also U.S. EPA, I-

U.S. G G E S: 1990-2007

(2009), https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/ les/2015-12/documents/ghg

2007entire_report-508.pdf.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

52 ELR 10730 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 92022

oversight typical of other industries, despite their well-doc-

umented negative impact on the environment.

36

e health

implications of CAFOs are also signi cant. e con ne-

ment of large numbers of animals in such inhumane and

unnatural conditions creates risks for both the animals and

the humans who work inside and live nearby.

37

Indeed, epidemiological concerns reach far beyond the

boundaries of CAFO sites and the communities that sur-

round them. CAFOs present unique opportunities for

cross-species transmission of in uenza.

38

Respiratory virus

outbreaks, not unlike the COVID pandemic, can spread

rapidly among both animal and human populations. e

industry is also known for the overuse of antibiotics, which

are needed to keep animals alive in con ned conditions,

leading to antibiotic resistance.

39

In 2019, the American

Public Health Association called for a moratorium on

new and expanding CAFOs due to the overwhelming

evidence of the harms they cause and the lack of proper

regulation.

40

It is well-documented that CAFOs negatively

impact a farmer’s sovereignty, pose public health risks, pro-

mote inhumane treatment of animals, perpetuate environ-

mental injustices, and cause an overall loss of democratic

self-governance.

41

In the sections that follow, we identify how RTFLs

enable these outcomes and consider how a more distrib-

uted agricultural system provides promise for correcting

this rural wrong.

II. Right-to-Farm Laws

RTFLs exist at the nexus of the rapid expansion of large-

scale, industrialized agriculture and the decline of a more

distributed agricultural system. By 1982, an initial wave

of RTFLs covered most of the United States. At that time,

there were 2.24 million farms spanning over 987 million

36. See GAO R, supra note 35; see also American Public Health Associa-

tion, Policy No. 20194, Precautionary Moratorium on New and Expand-

ing Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (Nov. 5, 2019), https://

www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/

policy-database/2020/01/13/precautionary-moratorium-on-new-and-

expanding-concentrated-animal-feeding-operations; see also B F. K

., J H C L F, I F

A P A: E I P

C’ P R (2013), https://clf.jhsph.edu/

sites/default/ les/2019-05/industrial-food-animal-productionin-america.

pdf.

37. See K ., supra note 36.

38. See, e.g., omas C. Moore et al., CAFOs, Novel In uenza, and the Need

for One Health Approaches, 13 O H 100246 (2021), available at

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352771421000367.

39. Mary J. Gilchrist et al., e Potential Role of Concentrated Animal Feeding

Operations in Infectious Disease Epidemics and Antibiotic Resistance, 115

E’ H P. 313 (2007).

40. American Public Health Association, supra note 36.

41. See P, P, R C, supra note 20; Douglas A.

Constance & Alessandro Bonanno, CAFO Controversy in the Texas Pan-

handle Region: e Environmental Crisis of Hog Production, 21 C

A. 14 (1999); Andrew D. McEachran et al., Antibiotics, Bacteria, and

Antibiotic Resistance Genes: Aerial Transport From Cattle Feed Yards Via Par-

ticulate Matter, 123 E’ H P. 337 (2015); P C

I F A P, P M T:

I F A P A (2008), https://www.

pewtrusts.org/-/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/phg/content_level_pages/

reports/pcifap nalpdf.pdf.

acres.

42

Since then, the number of farms has declined by

nearly 10%, and almost 100 million acres of farmland have

been lost.

43

RTFLs purport to protect agricultural operations

against nuisance lawsuits brought by those who estab-

lish residences in traditional farming areas, which often

allege pollution problems, odor, or other annoyances. To

receive RTFL protections, most states require agricul-

tural operations to be of commercial scale, meaning they

must sell products or goods for the commercial market.

44

RTFLs also commonly protect di erent types of agricul-

tural activities, but do not provide any speci c protection

for the farmland itself. Commonly, protected activities

include the production of various crops or livestock, as

well as processing, storage, and chemical application. No

state’s RTFL is speci cally tailored to protect traditional

or family-owned farms.

In a traditional common-law nuisance lawsuit, a suc-

cessful plainti may be entitled to monetary damages,

the nuisance-causing defendant may be ordered to alter

or abate the nuisance, or both.

45

However, an alleged nui-

sance-causing party often has a defense in nuisance law-

suits, known as “coming to the nuisance.” e “coming to

the nuisance” defense holds that “if people move to an area

they know is not suited for their intended use, they cannot

argue the preexisting uses are nuisances.”

46

In essence, the

“coming to the nuisance” doctrine is grounded in equity

and prioritizes the party that rst made use of the land.

47

“ is means courts had the power to reconcile disputes

fairly without being bound to statutory mandates or strict

rules of construction.”

48

us, even before the enactment of

RTFLs, existing agricultural land uses were protected from

42. N A S S, U.S. D

A, T 1. H H: 2012 E

C Y (2014), https://agcensus.library.cornell.edu/wp-content/

uploads/2012-New_York-st36_1_001_001.pdf [hereinafter 2012

E C Y].

43. N A S S, U.S. D A-

, T 1. H H: 2017 E C

Y (2017), https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/

Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US/st99_1_0001_0001.pdf [herein-

after 2017 E C Y].

44. See, e.g., N.J. R. S. §4:1C-7 (2022); M. R. S. tit. 7, §152(5)

(2022); N. R. S. §2-4402 (2022).

45. See Margaret R. Grossman & omas Fischer, Protecting the Right to Farm:

Statutory Limits on Nuisance Actions Against the Farmer, 1983 W. L. R.

95, 104 (1983).

46. N D. H, A L P’ L G N,

L U C, E L 18 (1992).

47. “ e term ‘equitable’ is de ned as just or consistent with principles of justice

and right, whereas ‘inequitable’ is de ned as not fair.” 27A A. J. 2

Equity §1 (citing B’ L D (14th ed. 2014)). Further:

Equity’s purpose is to promote and achieve justice and to do so

with some degree of exibility. Consequently, the powers of a court

sitting in equity are less hampered by technical di culties than a

court of law because a court of equity, being a court of conscience,

should not be shackled by rigid rules of procedure that preclude

justice being administered according to good conscience.

Id. §2.

48. In essence, a court in equity is a “court of conscience,” meaning it has a

degree of exibility in how it achieves justice. Id.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

92022 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 52 ELR 10731

nuisance suits brought by newly encroaching suburban

developments or other kinds of incompatible land uses.

49

On a national scale, there has been an incomplete

understanding of who or what bene ts from RTFLs and

how they vary among states. Because of this, we formed an

interdisciplinary team consisting of practicing lawyers and

social scientists to study the implications of RTFLs across

the United States. Over three years, we compiled all origi-

nal and current state RTFLs nationally and their legislative

preambles. We researched case law and collected all pub-

lished court opinions invoking RTFLs from all 50 states.

We did this via keyword searches through both Westlaw

and LexisNexis to identify case law where a state’s speci c

RTFL statute was cited.

We then used NVivo software to code the statutes and

cases, importing the original and the most recent versions

of the statutes, as well as the most recent court rulings for

each case. We also looked at each statute’s legislative his-

tory to determine how each state’s RTFL had changed over

time. We then created static sets and ran matrix queries

to identify trends, paying attention to attributes, including

key legislative provisions and the types of parties involved

in the cases (i.e., landowner, resident, CAFO, business

entity, etc.).

While comprehensive and current through the end of

calendar year 2021, our quantitative research is limited to

court opinions accessible through Lexis and Westlaw. In

this Article, we present statistical trends from cases where

a state’s RTFL was dispositive on an issue presented in

the case. All of these cases take place in state intermediate

appellate, state highest, federal district, and federal appel-

late courts, except for two heard by the Illinois Pollution

Control Board.

In addition to identifying quantitative trends, we also

completed in-depth qualitative analyses of each state. We

looked at each state’s RTFL, its legislative history, includ-

ing the dates and content of any amendments, and so on,

as well as how the courts have interpreted and applied

each state’s RTFL and speci c provisions thereof. In addi-

tion, we searched for secondary sources of information,

such as news articles and the like, to develop a greater

understanding of any public debates or opinions regard-

ing RTFL issues.

We then summarized each state’s law and any signi cant

cases pertaining to it. ese summaries are currently avail-

able online on the One Rural website.

50

Since our research

team consisted primarily of legal practitioners and social

scientists, additional qualitative research (either through

focused eldwork or through participant observation, or

both) also helped to inform this study.

We consider how agricultural exceptionalism drives

RTFLs in legislative intent and rhetoric, but in substance

49. In common-law cases, courts base their decisions on case precedent and

general principles of equity. is di ers from statutory law, wherein

courts must give deference to and base their decisions on applicable gov-

erning statutes.

50. See One Rural, Right-to-Farm Laws by State, https://onerural.uky.edu/right-

to-farm-map (last visited July 8, 2022).

contract private-property rights as traditionally conceived

by removing nuisance remedies for smallholders and, in

e ect, enabling forcible takings by corporate agriculture.

Simultaneously, agricultural exceptionalism has paved

the way for avoiding environmental, state, and federal

law. Together, agricultural exceptionalism has enabled the

consolidation of agriculture and the successful avoidance

of the legal frameworks that hold other comparably sized

industries responsible for their actions.

III. Results

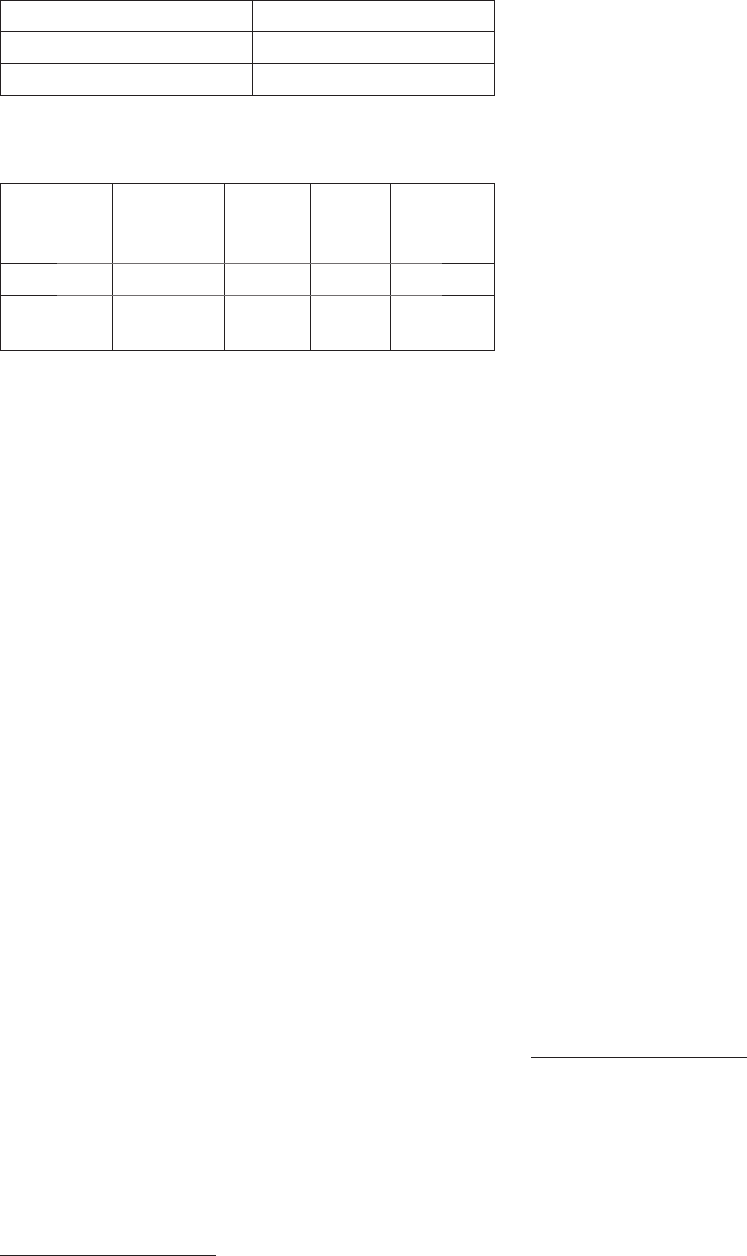

Of the 293 cases we analyzed that utilized RTFLs, 154

included CAFOs or business rms as parties, or 52.6% of

cases. By CAFOs we mean parties that we could identify as

large-scale industrialized livestock production facilities in

our reading of the case. By business rms, we mean incor-

porated entities like limited liability companies (LLCs),

corporations, and partnerships.

Out of the total body of cases we analyzed, 197 were

dispositive, meaning the RTFLs determined or related to

the case’s outcome. Of those 197 dispositive cases, CAFOs

or business rms were either plainti s or defendants in 101

cases, 51.2% of the total. is is a remarkably large num-

ber of business rms and CAFOs relative to the purported

purpose of RTFLs to protect family farms, which in con-

trast are often sole proprietorships. e U.S. Department

of Agriculture (USDA) reports that “[t]he vast majority

of family farms (89 percent) are operated as sole propri-

etorships owned by a single individual or family, and they

account for 59 percent of the value of production.”

51

Essen-

tially, the dispositive cases had a distribution of CAFO and

business rms like the parties in cases at large.

52

CAFOs and business rms are using and prevailing with

RTFLs at a level disproportionate to their share of produc-

tion in U.S. agriculture. CAFOs, as a party, account for

18.3% of the total dispositive cases (see Table 1). However,

they prevail in whole or in part in 69% of the cases they are

party to, or in 25 out of the 36 cases where they were plain-

ti s or defendants (see Table 2). By prevailing in part, we

mean that some part of the ruling was in favor of the party

at hand, but they did not win on all the merits of the case.

CAFOs, for example, won as defendants in 17 cases,

won as plainti s in 12 cases, and won in part in 5 cases.

Likewise, business rms tend to prevail in utilizing RTFLs,

but not as much as CAFOs do. (Note that the analyses

presented in Tables 1 and 2 are not mutually exclusive:

CAFOs can also be business rms like corporations, for

example, while corporations can also be CAFOs. How-

ever, one can exist without being the other). Business rms

received favorable rulings in 65% of the 92 cases they were

party to.

51. See E R S, USDA, A’ D F

F: 2018 E 18 (2018).

52. e descriptors we use for parties in litigation related to RTFLs are not nec-

essarily mutually exclusive. A party can be both a CAFO and a rm. Also,

rms can sue one another, which can make the same case enter into multiple

categories for party type as plainti , defendant, or split.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

52 ELR 10732 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 92022

Table 1. CAFOs and Firms as

Parties in Dispositive Cases

Party Type Total Dispositive Cases

CAFO 36

Business Firm (business entity) 92

Table 2. CAFOs and Firms Prevailing as

Defendants, Plaintiffs, and in Part

Prevailing

Party

Type

Prevail as

Defendant

Prevail

as

Plaintiff

Prevail

in Part

% of

Cases

Prevailed

CAFO 17 12 5 69%

Business

Firm 45 9 11 65%

IV. Discussion

e capacity for certain parties to prevail, particularly

business rms and CAFOs that do not easily align with

RTFL preamble language regarding the importance of

family farms, closely relates to speci c statutory provisions.

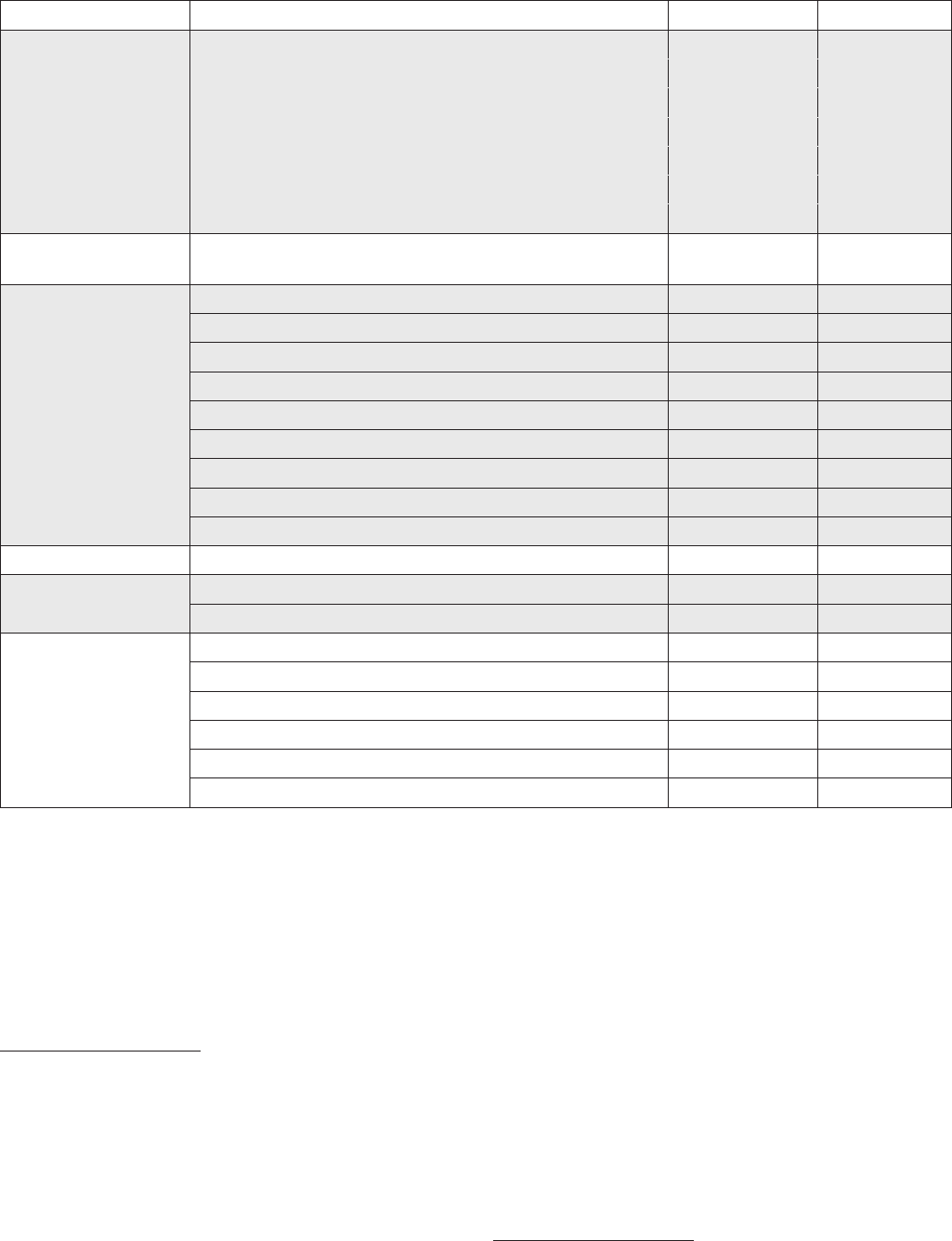

We identi ed statutory trends, and in Table 3, present lan-

guage that exists in at least one-quarter of U.S. states. e

broadly inclusive categories include conditions for immu-

nity from nuisance lawsuits; limitations on immunity;

de nitions of “protected operation”; limitations on dam-

ages and relief; the power of local governance; and whether

the statutes require operational compliance with the law to

receive protection.

V. Case Studies Examining RTFLs

We nd that while RTFLs were initially praised for pro-

tecting family farmers from urban expansion, they often

shield only large-scale industrial agriculture operations at

the expense of sole proprietor farmers and, more gener-

ally, rural property owners.

53

Following are case examples

demonstrating how these various types of provisions from

the categories in Table 3 shape court outcomes, leading to

favorable treatment of the largest industrial operations.

A. Conditions for Immunity From Nuisance Claims

and Limitations on Immunity

1. Protections for Operations That Have Existed

for Prescribed Time Period

Initially, when rst enacted, most state RTFLs stipulated

that for a farming operation to receive protection, it would

53. Mark B. Lapping & Nels R. Leutwiler, Agriculture in Con ict: Right-to-Farm

Laws and the Peri-Urban Milieu for Farming, in S A

N C 209 (William Lockeretz ed., Soil and Water Conservation So-

ciety 1987); Alexander A. Reinert, e Right to Farm: Hog-Tied and Nui-

sance-Bound, 73 N.Y.U. L. R. 1694 (1988).

need to exist before the party claimed a nuisance.

54

How-

ever, amendments have been made over time to protect

only particular types of agricultural activities and prac-

tices, regardless of whether or not those operations post-

date neighboring land uses. Many RTFLs now permit

new agricultural nuisances to develop through expansion,

changing practices or ownership, or through the mere exis-

tence of the operation for a stipulated amount of time—

often a period of just one year.

55

ese amendments have

eviscerated traditional notions of fairness by eliminating

the “coming to the nuisance” doctrine for nonagricultural

land uses.

Indeed, most RTFLs protect a farming operation once it

has been in operation for a speci c period of time. Nation-

ally, 48% of RTFLs protect operations once in operation

for one year (see Table 3). Eight states provide protections

based on varying periods of operation. For example, Min-

nesota, New York, and Oklahoma protect agricultural

operations from nuisance suits once they are in operation

for two years.

Initially, in Oklahoma, agricultural operations had to

pre-date neighboring nonagricultural activities to claim

protection from nuisance suits.

56

However, in 2009, the

state’s RTFL was amended to expand protections, even

for agricultural operations that were not there rst.

57

Now,

under Oklahoma’s RTFL, no nuisance action can be

brought against an agricultural operation that has “law-

fully been in operation for two (2) years or more prior to

the date of bringing the action.”

58

erefore, any type of

agricultural operation that has been in operation for two

years prior to the ling of a nuisance action will receive

RTFL protections.

59

is can be the case even if there is a

cessation or interruption in the farming operation.

2. Immunity Based on Defi nition of “Farm,” Despite

Changes in Size, Products, Practices, Etc.

RTFLs initially faced limited applicability in court when

plainti s could show a nuisance was caused by a sub-

stantial change in the farming operations. However, over

time, many RTFLs have evolved to provide cover in such

instances. Many RTFLs now protect farming operations

even if, among other things, their boundaries or size

change, or if di erent farm products are produced (see

Table 3 for speci c percentages).

60

54. is is the traditional “coming to the nuisance” doctrine, where a party can-

not move to an area and then claim an already existing land use is causing a

nuisance as explained above (see Reinert, supra note 53).

55. See examples at One Rural, New Mexico’s Right-to-Farm Summary, https://

onerural.uky.edu/right-to-farm/NM, and Arkansas’s Right-to-Farm Summa-

ry, https://onerural.uky.edu/right-to-farm/AR (last visited Aug. 2, 2022).

56. See O. S. tit. 50, §1.1 (1980).

57. 2009 Okla. Sess. Laws 147 (H.B. 1482) (amending, in relevant part, O.

S. tit. 50, §1.1).

58. O. S. A. tit. 50, §1.1 (West 2020).

59. Id. §1.1(C). Additional amendments in 2017 clari ed and added additional

protections so that the two-year clock does not restart even if an agricultural

operation expands or substantially changes its activities.

60. For example, in Michigan, a farm operation that conforms to “generally ac-

cepted agricultural and management practices” (GAAMPs) cannot be found

to be a nuisance because of a change in ownership or size, a temporary ces-

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

92022 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 52 ELR 10733

In practice, courts commonly hold that even if an agri-

cultural operation signi cantly changes the size or scope

of its operation, so long as whatever was taking place on

the land was previously some kind of agricultural use, the

operation is protected from nuisance claims. For example,

if a parcel of land had been used for row crops for many

sation or interruption of farming, enrollment in governmental programs,

adoption of new technology, or a change in type of farm product being

produced. M. C. L A. §286.473(3)(3) (2021). See also the

Kansas RTFL, which states:

(c) An owner of farmland who conducts agricultural activity pro-

tected pursuant to the provisions of this section:

(1) May reasonably expand the scope of such agricultural ac-

tivity, including, but not limited to, increasing the acre-

age or number of animal units or changing agricultural

activities, without losing such protection so long as such

agricultural activity complies with all applicable local,

state, and federal environmental codes, resolutions, laws

and rules and regulations

K. S. A. §2-3202 (West 2021).

years and then transitions into a 20,000-head cattle feed-

lot, surrounding neighbors would be barred from bringing

a nuisance suit against the feedlot, even if they attempted

to do so within the rst year of the feedlot’s existence.

61

Such decisions typically depend on the preexistence of a

di erent agricultural use (i.e., from crops to a massive cat-

tle con nement).

For example, in Indiana, amendments to the state’s

RTFL in 2005 created signi cant exclusions for what is

considered a signi cant change in an agricultural opera-

tion.

62

ese exclusions include (1)the conversion from one

type of agricultural operation to another type of agricul-

tural operation; (2)a change in the ownership or size of

the agricultural operation; (3) enrollment, reduction, or

cessation of participation in a government program; or

61. See, e.g., Himsel v. Himsel, 122 N.E.3d 935, 940 (Ind. Ct. App. 2019).

62. See 2005 Ind. Acts 23 (S.E.A. 267) (amending I. C §32-30-6-9).

Table 3. National Analysis of RTFLs

General RTF Criteria Specifi c Statutory Feature % Nationally # of States

Operations are

immune from

lawsuits . . .

if boundaries or size of operation change 28% 14

if change in locality 48% 24

if new technology used 30% 15

if operation produces a different product 26% 13

if there is a cessation or interruption in the farming operation 26% 13

once in operation for a year 48% 24

if there fi rst 46% 23

Operations are not

immune . . .

from lawsuits when they were a nuisance at the time it began 38% 19

Defi nition of the

farm, agriculture,

or farm operation

includes . . .

commercial 60% 29

facility 50% 25

land 50% 25

machinery 40% 20

noise, odor, or dust 40% 18

processing 34% 17

production 86% 43

use of chemicals or pesticides 48% 24

use of nutrients and/or fertilizer 38% 19

Attorney fees . . . awarded to a prevailing defendant 34% 17

Power of local

governance is . . .

superseded by RTFL generally 62% 31

superseded by RTFL in agricultural zone 12% 6

Requires

compliance

with . . .

generally accepted practices 78% 37

county law 44% 22

environmental law 28% 14

federal law 62% 31

other laws 52% 26

state law 66% 33

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

52 ELR 10734 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 92022

(4)the adoption of new technology.

63

Indiana courts have

interpreted these amendments to protect operations that

change from crops and smaller-scale livestock operations

to industrial-scale CAFOs.

In one case, the Indiana Court of Appeals held that a

farm, which consisted primarily of cropland and an accom-

panying historic dairy farm of approximately 100 cows,

converted into a 760-head dairy CAFO, did not constitute

a signi cant change.

64

In Parker v. Obert’s Legacy Dairy,

LLC, the court stated that “the Act removes claims against

existing farm operations that later undergo a transition

from one type of agriculture to another.”

65

erefore, it

found no “statutory support” for the neighboring plainti

farmer’s argument. Plainti s asserted that

[t]he Act was never intended to bar a nuisance claim by

landowners ... who have lived in an area for more than

40 years and then are impacted by a signi cant change

in use, such as the [concentrated] feeding operation,

which is established long after the acquisition of the

property and establishment of the use of the property by

the landowners.

66

While the court reasoned that “the size of the transfor-

mation, from 100 cows to 760 cows ... [was] substantial,”

it held the operation’s transition did not constitute a sig-

ni cant change under the RTFL. e court disagreed with

the notion that “the legislature could not have intended the

Act to apply to long-time residents whose daily, rural life

su ers at the hands of a ‘factory-like “mega-farm.”’”

67

us,

the state’s RTFL insulated the defendant’s dairy CAFO

expansion from a nuisance suit.

In a later case, another Indiana Court of Appeals ruled

similarly.

68

In Himsel v. Himsel, the court held that con-

version of a row crop farm to an 8,000-head hog CAFO

did not constitute a “signi cant change” under Indiana’s

RTFL.

69

Similar to the plainti s in Parker, the plainti s in

Himsel were neighboring farmers whose farming operations

pre-dated the conversion of the defendants’ crop farms into

massive industrial livestock production facilities. e Him-

sel court opined that the state’s RTFL was plainly “intended

to prohibit nonagricultural land uses from being the basis

of a nuisance suit against an established agricultural opera-

tion,” and that the law was “essentially a codi cation of the

doctrine of coming to the nuisance.”

70

63. I. C A. §32-30-6-9(d)(1)(A)-(D) (West 2021).

64. Conversion of part of a farm’s operations from cropland to support dairy, to

concentrated feeding operation, was not a “signi cant change” in the type

of agricultural operation, and, thus, after being in operation for more than

one year, was not a nuisance under the Right to Farm Act, even though the

number of cows kept on the property increased signi cantly. Id. §§32-30-

6-3(1)(A), 32-30-6-6, 32-30-6-9(d). Parker v. Obert’s Legacy Dairy, LLC,

988 N.E.2d 319 (Ind. Ct. App. 2013).

65. 988 N.E.2d at 323-25 (referencing I. C §32-30-6-9(d)(1)(A)

(2013)).

66. Id. at 324.

67. Id.

68. See Himsel v. Himsel, 122 N.E.3d 935, 940 (Ind. Ct. App. 2019).

69. Id. (emphasis added).

70. Id. at 943-44.

Here, the court essentially recognized the fact that the

original intent of the Act was not being served, as the defen-

dant’s crop farm did not transition to a CAFO until well

after the plainti s were there. Instead, the newly developed

CAFO postdated other agricultural uses in the area. ere-

fore, the court acknowledged that before the state’s RTFL

amendments were made in 2005, defendant’s CAFO

development would have constituted a signi cant change

in the agricultural operation, which would have rendered

RTFL protections inapplicable.

71

However, “[b]y specify-

ing that a conversion from one agricultural operation to

another is not a signi cant change, the Act restricts claims

against existing farm operations that later undergo a transi-

tion from one type of agriculture to another.”

72

us, the

traditional “coming to the nuisance” doctrine, as applied

by Indiana’s current RTFL, “now encompasses coming to

the potential future nuisance.”

73

Similarly, under Pennsylvania’s RTFL, no

nuisance action shall be brought against an agricultural

operation ... if the physical facilities of such agricultural

operations are substantially expanded or substantially

altered, and the expanded or substantially altered facility

has either: (1)been in operation for one year or more before

the date of bringing such action or (2)been addressed in

a nutrient management plan approved prior to the com-

mencement of such expanded or altered operation ... and

is otherwise in compliance therewith....

74

is statutory language has been interpreted by courts

in such a way that it essentially legalizes pollution

caused by the intensi cation of industrial animal agri-

cultural production.

75

In Burlingame v. Dagostin, for example, a Pennsylva-

nia court barred neighbors’ nuisance actions arising from

a CAFO spreading its liquid swine waste on surrounding

elds, which led to runo and bacteria pollution in nearby

waterways. e court’s rationale for protecting the facility

from nuisance litigation was based on the fact that it had a

nutrient management plan approved by the state’s Depart-

ment of Agriculture one year prior.

76

us, under Penn-

sylvania law, a crop farm that transforms into a massive

industrial livestock production facility, complete with an

adjacent wastewater reservoir containing millions of gal-

lons of waste, remains protected—regardless of resulting

air and water pollution.

Following the court’s logic, this means that if a CAFO

is not constructed one year prior to when a nuisance action

is brought, the operation can still be protected under the

RTFL so long as the operation has a waste plan approved

within the prescribed time period. is creates a substantial

71. Id. at 943.

72. Id.

73. Id. (emphasis added).

74. 3 P. S. §954(a)(1), (a)(2) (2021).

75. Burlingame v. Dagostin, 183 A.3d 462 (Pa. Super. Ct.), appeal denied, 648

Pa. 547 (Pa. 2018), appeal denied, McCabe v. Dagostin, 194 A.3d 559 (Pa.

2018).

76. Id.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

92022 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 52 ELR 10735

injustice in that neighbors can be barred from defending

themselves via a nuisance lawsuit prior to the construction

of a CAFO, before they become aware of any potential

problem. Even if plainti s le suit within one year of the

commencement of operations at a CAFO, Pennsylvania’s

RTFL will still shut the courthouse doors if the opera-

tion submits a waste management plan (WMP) with the

Department before that point.

77

ese cases exemplify how state RTFLs have evolved to

protect large-scale industrial and agricultural operations

to the detriment of other types of farming operations. In

many cases, RTFLs have done away with the traditional

“coming to the nuisance” doctrine to protect new indus-

trial operations and existing operations transitioning to

more intense industrial practices from nuisance claims by

other farmers that were there rst. is counteracts and

contradicts general principles of equity and fairness. It

shields industrial agriculture operations from accountabil-

ity for their negative impacts on surrounding farms and

rural areas by forcibly taking dimensions of property rights

from those neighboring such operations. It demonstrates

how agricultural exceptionalism, advanced by RTFLs,

provides industrialized agriculture special status and rights

over other types of farming.

B. Limitations on Damages and Relief

1. Fee-Shifting, Caps on Damages, and Other

Remedies

Some states also have dubious fee-shifting provisions that

only allow a successful defendant in a nuisance lawsuit to

recoup attorney fees and costs.

78

is poses a signi cant

risk for prospective plainti s, which may consist of just a

few family farm neighbors, who are often unable to pay

the opposing side’s legal fees should they be unsuccessful.

RTFLs in 17 states stipulate that attorney fees be awarded

to the prevailing defendant (Table 3). As Table 3 shows,

business rms and CAFOs most often prevail as defen-

dants, meaning they are positioned to bene t most from

such statutes. In contrast, only eight states award attorney

fees to the prevailing party generally.

ese provisions tend to sti e nuisance cases brought

against industrial and agricultural nuisances in the rst

place.

79

For example, in a 2000 lawsuit in Wisconsin, a

crop and cattle farmer claimed his neighbor’s commercial

cranberry operation was ooding his property, creating a

nuisance that curtailed his ability to graze his cattle and

use his farmland.

80

e court ruled in favor of the cran-

berry operation, arguing that the cattleman did not meet

77. Unless there is an adequate public notice and input process that is triggered

upon the submittal of CAFO WMPs with the Department, which there is

not, potentially a ected neighbors do not become aware of the fact that the

one-year time clock to bring a nuisance action is ticking.

78. See, e.g., W. S. §823.08(4)(b) (2021); 740 I. C. S. A.

70/4.5 (2021).

79. See, e.g., M. C. L §286.473 (2022).

80. Zink v. Khwaja, 608 N.W.2d 394 (Wis. Ct. App. 2000).

the required burden of proof that the cranberry operation

caused the ooding. Under the state’s RTFL, the court

ordered the plainti to pay the defendant cranberry opera-

tion’s litigation expenses, which included $24,000 in attor-

ney fees.

81

e cattleman subsequently argued that the fee-

shifting provision should not apply because the law was

not intended to pit one agricultural use against another.

Rather, the plainti asserted, the purpose of the state’s

RTFL was to hamper con icts between “agricultural and

other uses of land.”

82

e court disagreed, reasoning that

the plain language of the statute “unequivocally” man-

dated the recovery of fees by a defendant “in any action in

which an agricultural use or agricultural practice is alleged

to be a nuisance.”

83

Given that “litigation expenses” under the statute

include attorney fees, expert witness and engineering fees,

and the like,

84

the cost assessed to the plainti was signi -

cant. When litigation costs are shifted only to unsuccessful

plainti s but not unsuccessful defendants, the law e ec-

tually deters people from ling nuisance suits. Often, the

potential of having to bear both sides’ litigation expenses

can pose too great of a risk for prospective plainti s, espe-

cially if they consist of a single neighboring farmer.

Some states have amended their RTFLs to tighten their

anti-nuisance provisions limiting damage awards, among

other criteria, after an agribusiness entity loses a case.

85

Such tightening occurred in response to a series of nui-

sance cases brought against a hog industry giant, Smith-

eld Foods, given the amount of damages awarded to

plainti s. For example, more than 500 North Carolina

residents neighboring Smith eld-owned Murphy-Brown

hog facilities brought 26 lawsuits in federal court seeking

compensation for the decades of su ering endured because

of the adjacent hog facilities.

86

e awards, totaling mil-

lions, may seem like a signi cant amount of money. How-

ever, they may still not have the desired deterrent e ect on

future bad practices by the world’s largest hog producer—

held by WH Group Ltd., a nancial holding company

directed by Chinese executives and traded on the Hong

Kong Stock Exchange.

Despite non-domestic security bene ciaries, agribusi-

ness industry groups, including the North Carolina Farm

Bureau Federation, successfully pushed legislation signi -

cantly restricting the ability of impacted citizens to bring

future nuisance lawsuits against livestock operations.

87

e

81. See W. S. §823.08(4)(a) (2022), (4)(b).

82. Id. §823.08(1).

83. Zink, 608 N.W.2d at 398-99 (emphasis added).

84. W. S. §823.08(4) (2022).

85. Lisa Sorg, Neutering Nuisance Laws in North Carolina, NC P’ W

(Nov. 15, 2017), http://www.ncpolicywatch.com/2017/11/15/neutering-

nuisance-laws-north-carolina/.

86. Erica Hellerstein & Ken Fine, A Million Tons of Feces and an Unbear-

able Stench: Life Near Industrial Pig Farms, G (Sept. 20, 2017),

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/sep/20/north-carolina-hog-

industry-pig-farms.

87. See Sess. Law 2018-113, S.B. 711, Gen. Assemb., 2017 Leg. Sess. (N.C.

2018), available at https://www.ncleg.net/Sessions/2017/Bills/Senate/PDF/

S711v8.pdf; see also Sorg, supra note 85.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

52 ELR 10736 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 92022

new North Carolina Farm Act of 2018, which became law

despite a veto by the state’s governor (overridden by the

legislature), now makes it far more di cult for plainti s

to pursue such cases successfully. One such provision now

requires that plainti s live within one-half-mile of the

alleged nuisance, e ectively eliminating the capacity to

sue based on pollution plumes that travel further by air

or water. Beyond this, the livestock industry was success-

ful one year earlier in passing legislation capping the dam-

ages plainti s can be awarded, such that they can only be

compensated for the loss of the value of their property, but

not for the loss of quality of life. While this law was not in

e ect when the cases against Murphy-Brown were led, it

ensures against plainti s being compensated in any such

way in the future.

Along the same lines, fee provisions in Missouri were

tightened after a jury awarded neighbors $11 million in a

nuisance suit against Premium Standard Farms. Not long

after plainti s were successful in this case, new legislation

was passed into law signi cantly capping monetary dam-

ages that plainti s could be awarded to only the loss in

fair market value to their property.

88

Also, in New Mexico,

shortly after a set of nuisance cases were led against sev-

eral large-scale dairy operations that signi cantly impacted

neighbors, an amendment to the state’s RTFL was passed.

89

e amendment purported to protect the industry against

future actions allegedly generated by “out-of-state attorneys

seeking to put the state’s dairy industry out of business.”

90

Additionally, the American Legislative Exchange Council,

a coalition of large corporate interest groups, such as the

National Pork Producers Council, have created model anti-

nuisance laws for states to use, some of which have been

enacted verbatim.

91

C. Protection Through Restrictions on the

Power of Local Governance

1. Restrictions From Local

Governmental Regulation

While purporting to protect farming and farmland, RTFLs

not only strip individual landowners and farmers of the

ability to protect their property, but also impact the ability

of local governments to address agricultural nuisances and

the negative environmental impacts that accompany them.

Indeed, local laws and regulations are often restricted or

superseded by RTFLs, depending on the state. RTFLs in

31 states speci cally state that they supersede the power of

local governments to act, while six states limit local gov-

ernance in agricultural zones (see Table 3). ese kinds of

88. Sorg, supra note 85.

89. See Jessica Johnson, “Right-to-Farm” Bill Tramples Rights of Residents, A-

J. (Feb. 20, 2016), https://www.abqjournal.com/727013/rightto-

farm-bill-tramples-rights-of-residents.html.

90. Personal communication by Danielle Diamond with an individual attend-

ing a legislative committee hearing on the bill (Feb. 2016).

91. Sorg, supra note 85.

provisions exacerbate the other barriers faced by rural com-

munities in addressing environmental harms.

RTFLs often also speci cally prohibit local zoning con-

trols and regulation over land uses in agricultural areas

and/or prevent local governments from having authority

over where CAFOs are located. In essence, CAFOs and

other intense agricultural uses have largely become exempt

from local zoning laws.

92

is removes the power of local

communities to choose the kind of agriculture present in

their communities, as well as their ability to decide appro-

priate locations for intense agricultural uses. Many RTFLs

explicitly restrict local authority over these kinds of deci-

sions and the ability of local governments to deal with pub-

lic nuisances occurring on agricultural land.

93

For example,

Arkansas’ RTFL states:

Any and all ordinances adopted by any municipality or

county in which an agricultural operation is located mak-

ing or having the e ect of making the agricultural opera-

tion or any agricultural facility or its appurtenances a

nuisance or providing for an abatement of the agricultural

operation or the agricultural facility or its appurtenances

as a nuisance in the circumstances set forth in this chapter

is void and shall have no force or e ect.

94

In general, state statutes grant land use zoning powers to

local governments through their police powers. Police pow-

ers are broadly intended for governments to promote public

health, safety, morals, and general welfare.

95

Local govern-

ments use these powers to regulate and control the types

92. For example, in Illinois, most businesses that store, treat, transport, or dis-

pose of waste are required to obtain permits from the Illinois Environmental

Protection Agency. However, before a business can proceed with a permit-

ting application for a “pollution control facility” with the state agency, it

must obtain approvals from the local siting authority (i.e., the county or

other municipal entity with jurisdiction). See 415 I. C. S. 5/39.2

(2022). County boards or governing municipal bodies are to provide for

notice, hearing, and public input on permitting applications, and may also

impose conditions on the land use that are not inconsistent with state regu-

lations. See id.

However, when it comes to CAFOs, counties have no authority over

siting decisions, and there are no constitutional due process protections for

most potentially a ected parties. See Livestock Management Facilities Act,

510 I. C. S. 77/1 et seq. (2022). See also Helping Others Maintain

Environmental Standards v. Bos, 941 N.E.2d 347, 362 (Ill. App. Ct. 2010),

where the court found that plainti s did not have standing to seek review of

an Illinois Department of Agriculture siting decision of a CAFO. [Editor’s

Note: Danielle Diamond worked with the Illinois citizen group Helping

Others Maintain Environmental Standards in her capacity as a Research

Associate for Northern Illinois University, as well as in her capacity as an

organizer and policy advocate with the Illinois Coalition for Clean Air &

Water and the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project.]

93. A. C A. §2-4-105 (West 2022).

94. Id.

95. Local land use regulations are subject to constitutional limitations, such as

governmental takings, due process, and so forth. A constitutional “taking”

typically requires compensation when government action results in no other

economically viable uses for the land. Due process protections ensure all

parties involved (landowners and those who may be a ected by a zoning

action) have procedural rights, such as the rights to notice, hearing, and

an impartial decisionmaker. Substantive due process, the Equal Protection

Clause, and First Amendment also apply in land use decisions. Under the

Supremacy Clause, the federal government and/or states can preempt cer-

tain land use regulations through express preemptions (if it can be assumed

the state or federal government intended to regulate an entire eld) and/or

if a local zoning requirement directly con icts with state or federal law.

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

92022 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 52 ELR 10737

of land uses allowed in certain areas through designated

“zoning districts” and by imposing speci c development

controls, such as lot sizes, setbacks, building appearances,

and so on. Also, certain types of land uses that are not

automatically allowed in speci ed zoning districts can be

allowed on a case-by-case basis via conditional or special

use permits or through variances, etc.

96

In essence, zoning powers enable local governments to

oversee community growth to ensure that varying kinds

of land uses are compatible at their respective locations.

97

Zoning powers also include the ability to determine if and

when certain types of industries can adjust their practic-

es.

98

Again, these local powers are commonly restricted

or prohibited by state RTFLs or, in some cases, via other

state laws preempting the eld of regulation over a type of

agricultural practice and even through farmland preserva-

tion statutes.

99

For example, an Illinois court dealt directly with the

applicability of the state’s agricultural exemption law. In

County of Knox ex rel. Masterson v. Highlands, L.L.C.,

neighbors of a large-scale hog con nement facility chal-

lenged the issuance of construction permits by their county

allowing the facility to expand.

100

e neighbors appealed

96. e purpose behind local land use zoning laws is to separate incompatible

land uses so that they do not interfere with each other or otherwise adversely

impact public health and safety.

97. For example, a municipality might restrict the location of race car tracks in

a residential zoning district as a measure to protect the health and safety of

existing residents.

98. All other industries are subject to these kinds of controls. For example,

music and dance halls are required to incorporate modern sound equip-

ment and sound bu ers into their business models so as not to impact

neighboring landowners. All di erent categories of landowners are re-

quired to conduct themselves so they do not unreasonably interfere with

others’ ability to use and enjoy their own property. e results often lead

to innovation and advancement. In agriculture, however, state legislatures

have dictated that agriculture operations are not required to act in the

same neighborly manner.

99. e Illinois Counties Code restricts counties from zoning powers

exercised so as to impose regulations, eliminate uses, buildings, or

structures, or require permits with respect to land used for agricul-

tural purposes, which includes the growing of farm crops, truck

garden crops, animal and poultry husbandry, apiculture, aquacul-

ture, dairying, oriculture, horticulture, nurseries, tree farms, sod

farms, pasturage, viticulture, and wholesale greenhouses when such

agricultural purposes constitute the principal activity on the land.

55 I. C. S. A. 5/5-12001 (2022). Also under the state’s Live-

stock Management Facilities Act, counties are only allowed to give the state

Department of Agriculture an “advisory non-binding” opinion as to wheth-

er a livestock facility (utilizing a lagoon or housing more than 1,000 animal

units) should be permitted within their jurisdictions. e Act states that a

“county board shall submit ... an advisory, non-binding recommendation

to the Department about the proposed new facility’s construction.” 510 I.

C. S. A. 77/12(b) (2022). is statute thus preempts counties

from having a meaningful role in the siting of new CAFOs, as the Depart-

ment of Agriculture can and commonly does override county recommenda-

tions objecting to the construction of new facilities.

Another example is Tennessee. Tennessee’s code regarding counties ex-

plicitly states that the “powers granted to counties by this part do not in-

clude the regulation of buildings used primarily for agricultural purposes; it

being the intent of the general assembly that the powers granted to counties

by this part should not be used to inhibit normal agricultural activities.”

T. C A. §5-1-122 (West 2022). ese kinds of statutes again

show the pervasiveness of agricultural exceptionalism that has in uenced

policy even beyond state RTFLs.

100. 705 N.E.2d 128, 130 (Ill. App. Ct. 1998). is case was not included in

our quantitative analyses on RTFLs. It is being referred to in this context for

discussion purposes to demonstrate how agriculture can receive exemptions

the county permits, which then triggered a county zoning

resolution that stayed the permits for the expansion.

101

e

facility appealed the county’s action in circuit court.

In their defense, the county and other objectors asserted

that the state’s agricultural exemption

102

did not apply and,

therefore, the county had the jurisdiction to restrict the

livestock facility’s proposal to expand. e county also

argued that the animal con nement operation was more

closely related to an “industry” rather than “agriculture.”

103

is was due to its “potential for a ecting the public

health, safety, comfort and general welfare of its environs”

and that “as a matter of public policy, the potential envi-

ronmental stress created by such an operation warrant[ed]

a 21st-century clari cation of what agriculture is in this

State.”

104

Despite a strong dissenting opinion from a prior

proceeding, the court rejected the county’s argument and

found in favor of the hog con nement proposal.

105

Another case in Iowa involved a challenge to a local

county board’s e ort to regulate CAFOs by the Worth

County Farm Bureau. Worth County enacted its Rural

Health Family Farm Protection Ordinance, a “thought-

ful product of the cumulative work of the Worth County

Board of Health, a citizen advisory committee, and the

Board of Supervisors,” to address concerns over air pol-

lution and water contamination caused by industrial

livestock operations. Responding to the Farm Bureau’s

ordinance challenge, the Iowa Supreme Court held that

it was expressly preempted by state statute, which “left no

room for county regulation.”

106

Additionally, agricultural use exemptions are often

worded to prevent local regulation over land being used

for “agricultural purposes.” In e ect, Iowa creates two-

way zoning for agricultural exceptionalism: the creation of

from local regulation through other statutory means. In this particular case,

the court considered the applicability of the Illinois Counties Code as op-

posed to the state’s RTFL.

101. Id.

102. e court stated:

e statutory authority granting Knox County the right to regulate

and restrict the location and use of structures is found in section

5-12001 of the Counties Code (55 ILCS 5/5-12001) (West 1996).

is section expressly states that counties have no authority to im-

pose regulations or require permits with respect to land used or to

be used for agricultural purposes.

Id. at 131.

103. County of Knox ex rel. Masterson v. Highlands, L.L.C., 723 N.E.2d 256,

264, 30 ELR 20226 (Ill. 1999).

104. Id.

105. Id.; see also County of Knox ex rel. Masterson v. Highlands, L.L.C., 705

N.E.2d 128 (Ill. App. Ct. 1998). Around the same time as the Highlands

litigation was taking place, the state enacted a law preempting the county

from having any binding authority to make siting decisions regarding CA-

FOs within their jurisdictions. Other laws preempting or restricting county

or local municipal controls have similarly been enacted in other states. For

example, Wisconsin has signi cantly limited local control over livestock

facility siting permits. Wisconsin’s livestock siting law “not only expressly

withdraws political subdivisions’ power to disapprove livestock facility siting

permits absent some narrow exceptions, but also expressly withdraws politi-

cal subdivisions’ power to impose certain conditions when they grant such

permits.” Adams v. State Livestock Facilities Siting Review Bd., 820 N.W.2d

404, 417, 42 ELR 20149 (Wis. 2012). “ is imposition by the legislature

leaves no authority to the political subdivisions to grant permits in a manner

inconsistent with the Siting Law.” Id.

106. Worth County Friends of Agric. v. Worth County, 688 N.W.2d 257, 265

(Iowa 2004).

Copyright © 2022 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120.

52 ELR 10738 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER 92022

agricultural areas a orded nuisance protections for farm-

ing operations; and the simultaneous prohibition of zoning

powers over agricultural areas.

107

Iowa’s RTFL authorizes

counties to create agricultural land preservation areas by

passing ordinances to preserve land for agricultural use.

108

However, counties are prevented from regulating CAFOs

in these areas.

109

State law restricts local authority to enact

any ordinances that would regulate any condition or activ-

ity occurring on land used for the production, care, feed-

ing, or housing of animals.

110

It deserves to be mentioned that Iowa is one of the only

states where a supreme court has held an RTFL uncon-

stitutional. In Bormann v. Board of Supervisors, the Iowa

Supreme Court ruled that restricting regulation in agricul-

tural land preservation areas constituted an unjust taking,

violating the constitutional protections a orded private-

property ownership.

111

e court reasoned that the RTFL

created an easement without just compensation for activi-

ties that would have been considered a nuisance if the land

had not been designated as an agricultural area. However,

the legal capacity to regulate CAFOs in such agricultural

areas remains constrained.

In Idaho, cities, counties, taxing districts, and other

political subdivisions are prohibited from enacting any

ordinances or resolutions declaring “any agricultural oper-

ation, agricultural facility or expansion thereof that is oper-

ated in accordance with generally recognized agricultural

107. See I C A. §335.2 (2022) (“no ordinance adopted under this

chapter applies to land, farmhouses, farm barns, farm outbuildings or other

buildings or structures which are primarily adapted, by reason of nature and

area, for use for agricultural purposes”).