Rick Tischaefer

Biological Science Technician

USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services

Bismarck, North Dakota

Human-Wildlife Conflicts

The coyote (Canis latrans; Figure 1) is a

medium-sized member of the canid family.

Once primarily found in western deserts

and grasslands, coyotes have expanded

their range across North America and into

diverse habitats, including urban areas.

This expansion occurred during a time of

extensive habitat change and efforts by

people to suppress coyote populations to

prevent damage.

Coyotes can cause a variety of conflicts

related to agriculture, natural resources,

property, and human health and safety.

This document highlights a variety of

methods for reducing those conflicts.

Coyotes are a highly adaptable species

and may become habituated to some

management tools and techniques used to

reduce or prevent damage.

Wildlife Damage Management

Technical Series

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service

Wildlife Services

November 2020

Coyotes

Figure 1. Coyote

(Canis latrans).

Quick Links

Human-Wildlife Conflicts 1

Damage Identification 2

Management Methods 4

Economics 21

Species Overview 22

Legal Status 26

Glossary & Key Words 28

Resources 29

Appendices 32

Agriculture and Livestock

Coyotes are omnivores (i.e., eat plants and animals) and

pose substantial threats to agricultural crops and

livestock. They forage on agricultural crops, such as

watermelons, sweet corn, and berries. Coyote

depredation on poultry and livestock (e.g., sheep,

cattle, goats), and non-traditional livestock and

specialty breeds (e.g., miniature horses, donkeys,

game birds, rabbits) is frequently a concern when

both share the same environment. Furthermore,

coyotes may spread the parasite Neospora caninum

to livestock, causing abortion and neonatal mortality

in cattle.

Human Health and Safety

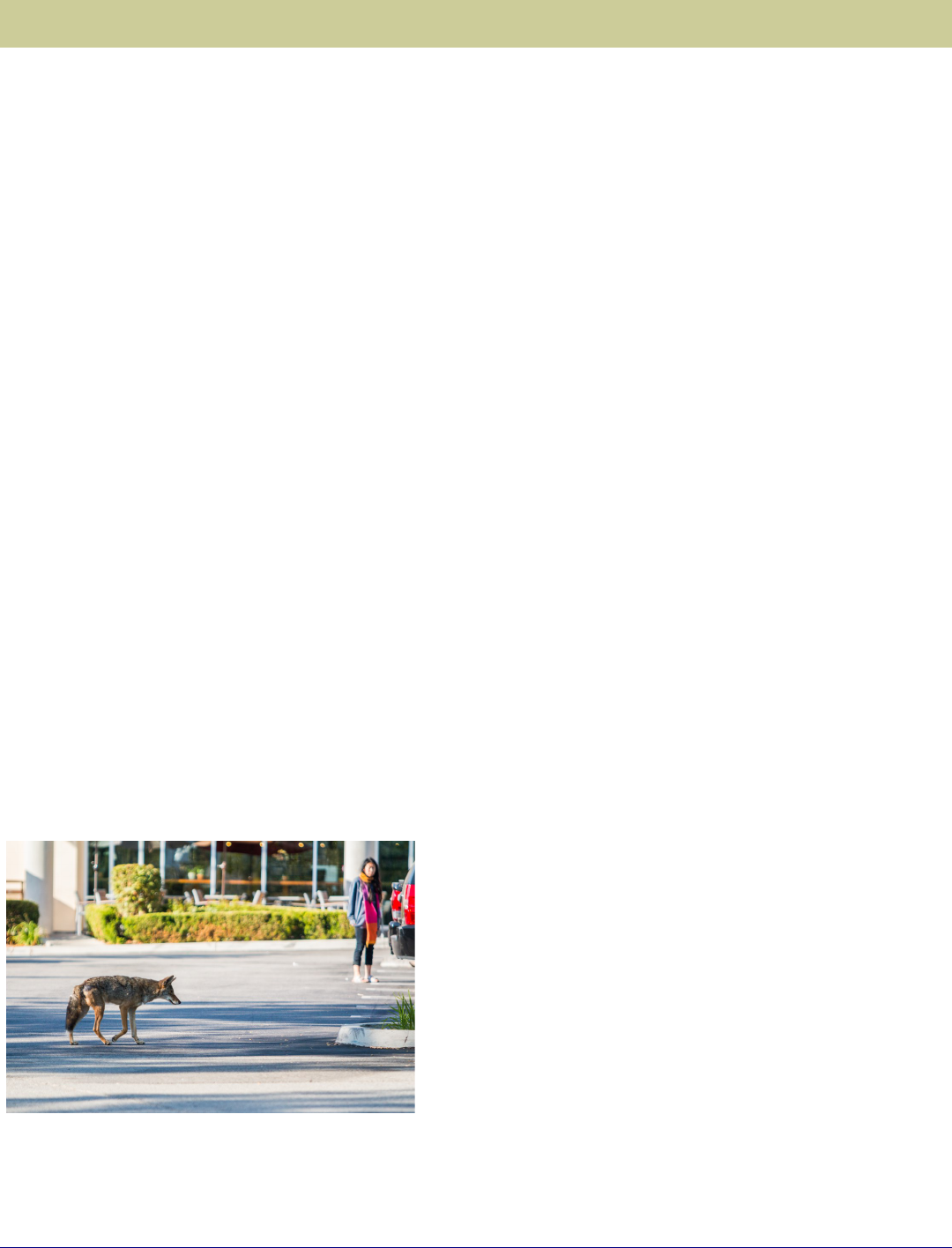

Where coyotes occur near people, they sometimes

become acclimated to human presence (Figure 2).

Coyotes may attack and kill pets, other domestic

animals, and sometimes threaten or attack people.

Additionally, coyotes pose aviation hazards when they

occur on airports. In fact, coyotes are one of the

terrestrial mammals most frequently struck by airplanes

according to the Federal Aviation Administration’s

National Wildlife Strike Database, 1990-2018.

Coyotes can carry transmissible diseases and parasites, such

as rabies and Echinococcus granulosus tapeworms, which

may threaten human health and safety.

Natural Resources

Coyote predation can impact the recovery of threatened

and endangered species, such as black-footed ferrets

(Mustela nigripes) and ground nesting birds (e.g., piping

plovers (Charadrius melodus) and least terns (Sternula

antillarum)).

Property and Nuisance Issues

Coyotes feed upon and scatter human garbage; eat

unattended pet food or residual seed below feeders; and

chew on rigging, straps or tie downs made of leather or

treated with compounds containing sweet resin or sulphur.

Damage Identification

Agriculture and Livestock

Many animals can cause damage to agricultural crops

and livestock. Therefore, it is important to accurately

identify the species responsible to select the most

appropriate methods and techniques to include in an

effective integrated damage management program.

First, search for sign (e.g., tracks, scat, fur, carcass parts)

by walking in ever expanding circles around the

depredation site (it is also helpful to use a trained dog for

this purpose). Check animal travel corridors for sign to aid

in the investigation. Trail cameras may also be useful for

monitoring a site. If ground conditions are suitable, rake a

clear area in a suspected animal travel corridor and look

for fresh tracks on future visits. In urban or suburban

areas, scatter a thin layer of flour over dry hard surfaces

(decks, sidewalks, driveways, or porches). Look for tracks

in the following days to determine animal presence.

Figure 2. Coyotes in cities and suburban areas often become less wary

of people.

Page 2

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Next, examine the damaged resource. Coyotes eat smaller

fruits and vegetables whole but can also cause extensive

damage to larger fruits and plant parts. For example,

coyotes will bite into and eat parts of watermelons. They

will also knock down or rip out sweet corn plants by the

roots and eat portions of a single ear before moving onto

another plant. As generalist omnivores, coyotes may eat

any type of food crop depending on local conditions and

the availability of natural alternatives.

Regarding livestock depredation, examine the evidence to

determine if the animal died of natural causes (and was

later scavenged) or if it was killed by a predator. A timely

evaluation of the depredation site is critical. Talk to the

producer. If possible, ask them to cover the carcass to

prevent scavengers from feeding and destroying evidence.

Locate the attack, kill, and feeding sites and search for

sign. Observe the remaining livestock in the vicinity to

determine if additional stock are missing (e.g., an adult

without young).

Begin a field necropsy by noting the position of the

carcass. Predated animals are rarely lying in a natural

position. Examine the carcass for wounds, hemorrhaging,

broken bones, and feeding to determine the cause of

death. Hemorrhaging around any bite mark would indicate

the prey was alive at the time of the bite. Do not confuse

bruising (localized and dark in color) with conditions

caused by decomposition (body fluids collect and cause

discoloration). Blood from wounds of injured animals is

thick and easily clots; differing from the thin reddish fluids

resulting from decomposition. Note the number, size,

depth, and location of tooth puncture marks. Size and

spacing between canine teeth is characteristic for each

predator species. Detailed notes and photographs will help

document and assist in the investigation.

Signs of coyote damage to livestock are diverse and may

include the following:

• Eating the ears, noses, or tails of newborn calves;

• Killing of small ungulates like calves, lambs, and fawns

which are easily overtaken by coyotes because of their

size. For prey that is larger than a coyote, a rear leg

may be damaged, or hamstring torn or rendered

useless during an attack;

• Biting the throat (behind jaw hinge and below ear).

There may be multiple bites in a location due to a lack

of penetration or loss of grip. Calves or larger livestock

are often attacked at the flank or hindquarters. Small

livestock may be killed by a single bite through the

head;

• Distinctive puncture wounds. Location and spacing of

puncture wounds will aid in determining the species.

There will be slight measurement variations with age

and between eastern and western coyotes. Generally,

an upper jaw canine tooth is ¼ inch (0.6 centimeters

(cm)) in diameter and the puncture wound pattern of

both upper canine teeth is 1¼ inches (3.1 cm) wide;

and a lower jaw canine tooth is inch (0.4 cm) in

diameter and the puncture wound pattern of both

lower canine teeth is 1⅛ inches (2.8 cm) wide;

• Feeding on a carcass just behind the ribs. The heart,

lungs, and liver or milk-filled stomach are often eaten

first. In larger carcasses, feeding may begin on the

hindquarters, near the anus or udder;

• Scattering remains (wool or hair, stomach contents,

bones, etc.) or moving a carcass (small animals) or

parts of a carcass to a safer or more protected area for

feeding;

• Presence of coyote sign near the location of the

damage or attack, as well as the feeding site; and

• Killing of multiple animals.

Page 3 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Human Health and Safety

In cities and towns across the U.S., coyotes are thriving.

This increased contact with people sometimes leads to

bolder and more aggressive behaviors towards people and

pets. Factors which may lead to or allow for the

continuation of these aggressive behaviors include:

• Lack of fear by some coyotes likely due to changes in

interactions between coyotes and people (e.g., people

more likely to tolerate coyote presence, coyotes are

rarely hunted or trapped in urban areas);

• Intentional feeding of coyotes by people; and

• Reduction in management and animal control

programs that selectively remove problem coyotes.

Many municipalities have developed urban coyote

management plans that describe coyote actions and

behaviors, and recommend management responses. A list

of progressively bolder coyote behavior is described in

Table 1. Many preventative actions (e.g., public education,

stopping intentional and unintentional feeding, hazing) can

be taken in the early stages to help curtail aggression.

Coyotes can carry a variety of diseases and parasites

which are easily transferrable to pets and people. Spread

can occur through direct or indirect contact with bodily

fluids and scat. In some cases, people may have no direct

contact with coyotes, but may be at risk through a pet’s

contact with coyotes or coyote scat. Pet vaccinations are

an important tool for preventing the transfer of some

diseases, such as rabies, canine distemper, and canine

parvovirus.

Management Methods

Responsible and professional reduction or elimination of

wildlife damage is the goal of wildlife damage management

practitioners. This is best accomplished through an

integrated approach. No single method is effective in every

situation, and success is optimized when damage

management is initiated early, consistently, and adaptively

using a variety of methods. Because the legality of different

methods vary by state, consult local laws and regulations prior

to the implementation of any method.

For a summary table of coyote management methods,

please see Appendix I.

Animal Husbandry

Animal husbandry includes a variety of activities related to

the care and attention given to livestock. Generally, when

the frequency and intensity of livestock husbandry

increases, so does the degree of protection from

predators.

Page 4

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

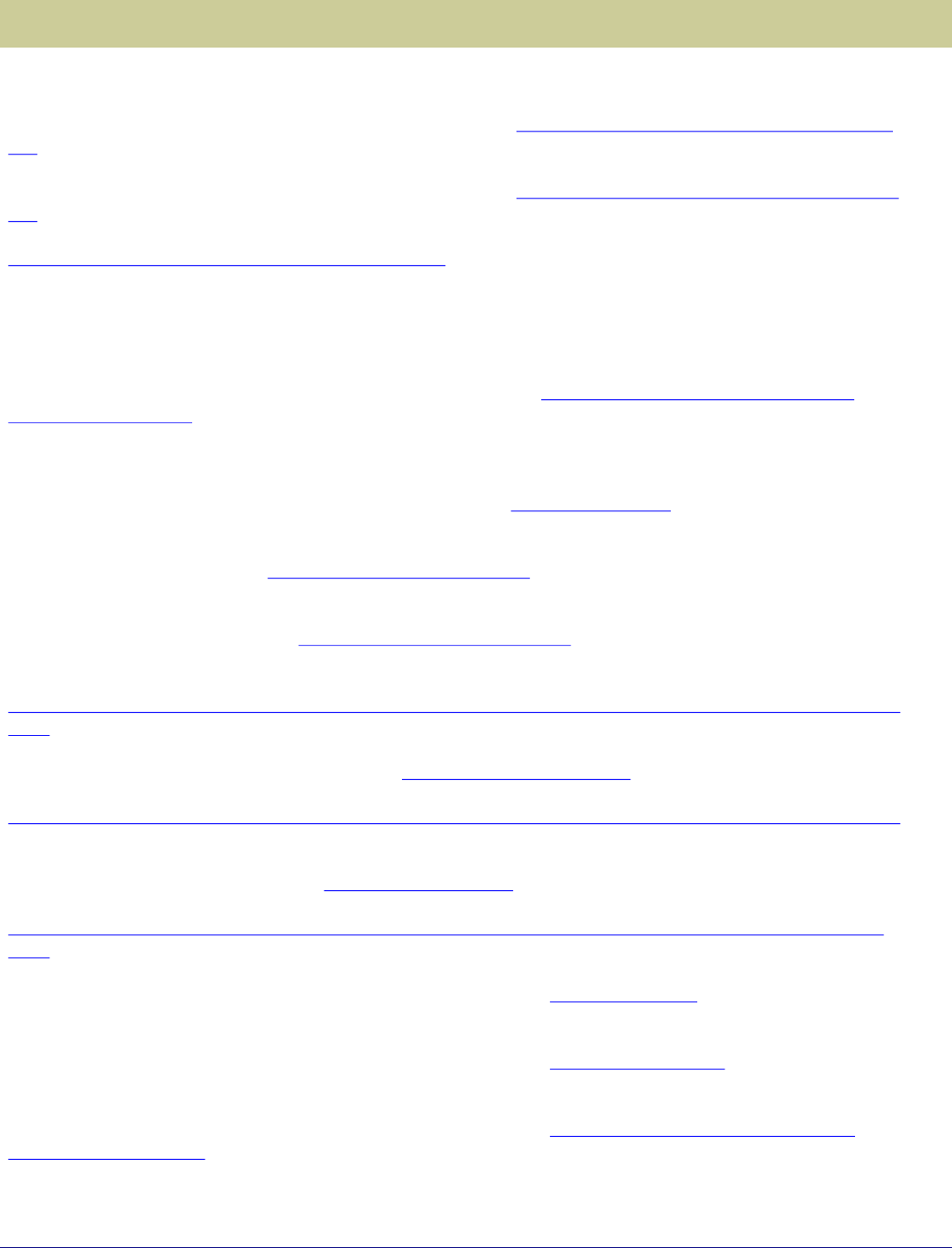

Stage Descriptive Behavior

1

An increase in observing coyotes on streets or

property at night

2 An increase in coyotes approaching people or

taking pets at night

3

Early morning and late afternoon daylight

sightings of coyotes

4 Daylight sightings of coyotes pursuing or taking pets

5 Coyotes attacking pets on a leash or in close

proximity to their owners

6 Midday sightings in areas where children congregate

7 Midday aggression towards people

Table 1. Progression of coyote aggression compiled by Timm, Coolahan, Baker

and Beckerman (2007).

Altering animal husbandry to reduce wildlife damage can

be effective but may have limitations. For example,

confinement may not be possible when grazing conditions

require livestock to scatter. Hiring extra people, building

secure holding pens, and adjusting the timing of births is

usually expensive. The expense associated with a change

in husbandry practices may exceed the savings.

Flock and Herd Health

Poultry and livestock breeds with stronger flocking and

herding behaviors may be less vulnerable to coyote

depredation. Coyotes often take advantage of prey with

compromised health conditions. Proper feeding and care of

livestock helps ensure stronger young that are less vulnerable

to coyote depredation.

Record Keeping

Good record keeping and animal identification systems are

invaluable in a livestock operation. Records help producers

identify loss patterns or trends related to coyote depredation,

as well as determine what type and amount of coyote

damage management is feasible. Records also identify

critical problem areas that may require attention. For

example, records may show that losses to coyotes are high in

a particular pasture in early summer, requiring proactive

preventive management. Owners who do not regularly count

their livestock may suffer fairly substantial losses before

realizing a problem exists. Such delays make it difficult to

accurately determine if losses are due to coyotes.

Birthing and Raising Young

Both the season and location of birthing and raising young

livestock can affect the severity of coyote depredation.

Coyote related losses of young livestock are typically the

highest from late spring through September when adult

coyotes are feeding young. A fall birthing program is one

option that avoids large numbers of young animals on the

landscape during periods when coyote depredation is high.

Synchronized or group breeding helps shorten birthing

periods and reduces exposure of small livestock to

depredation. When birthing within a concentrated period,

however, extra labor and facilities may be necessary. Some

producers practice early weaning and do not allow young to

go to large pastures, thus reducing coyote depredation. This

also gives orphaned and weaker animals a greater chance of

survival.

Where practical, sheds, pens, small pastures or paddocks for

birthing or raising young livestock can increase survival.

Increased human presence or activity around livestock also

Page 5 U.S. Department of Agriculture

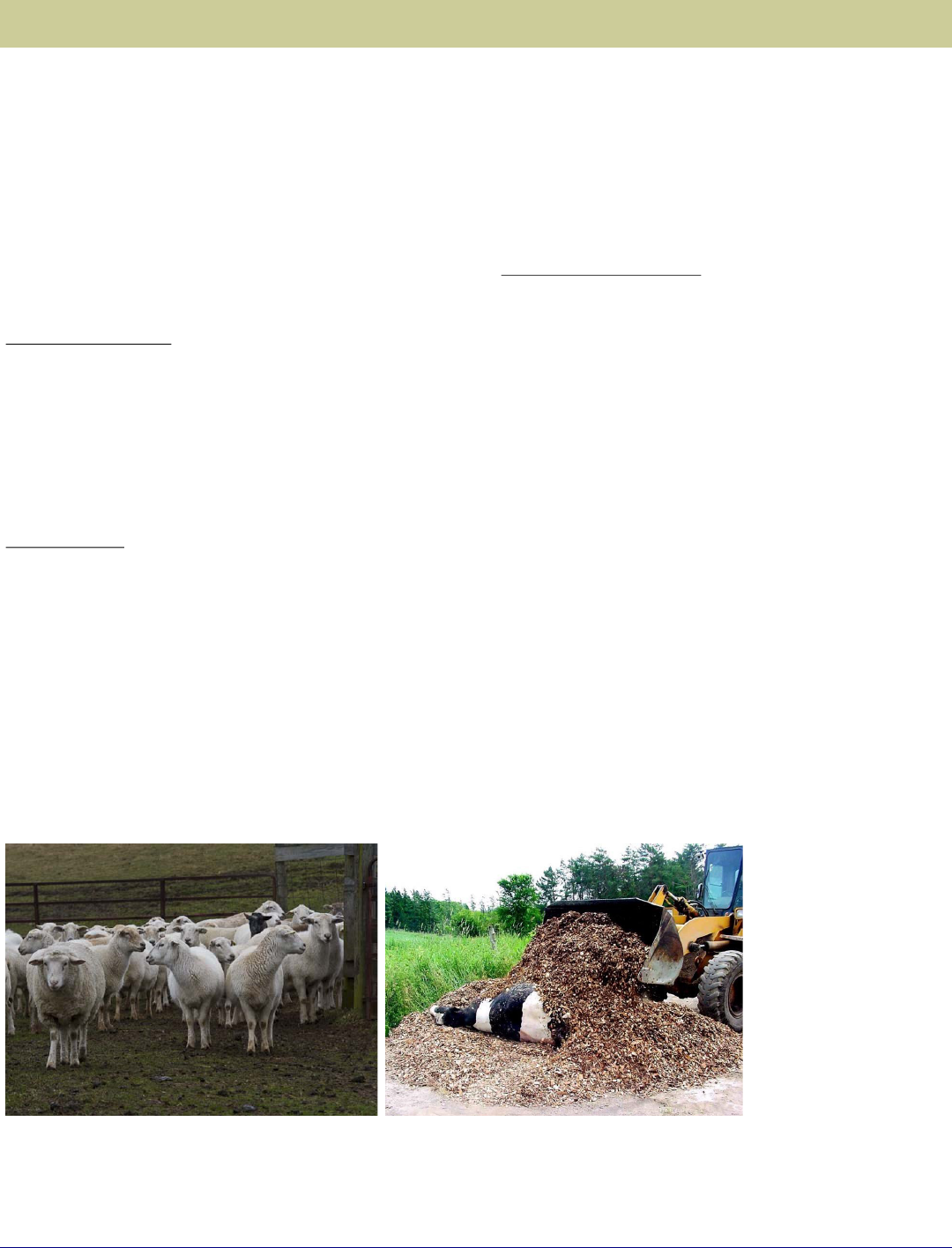

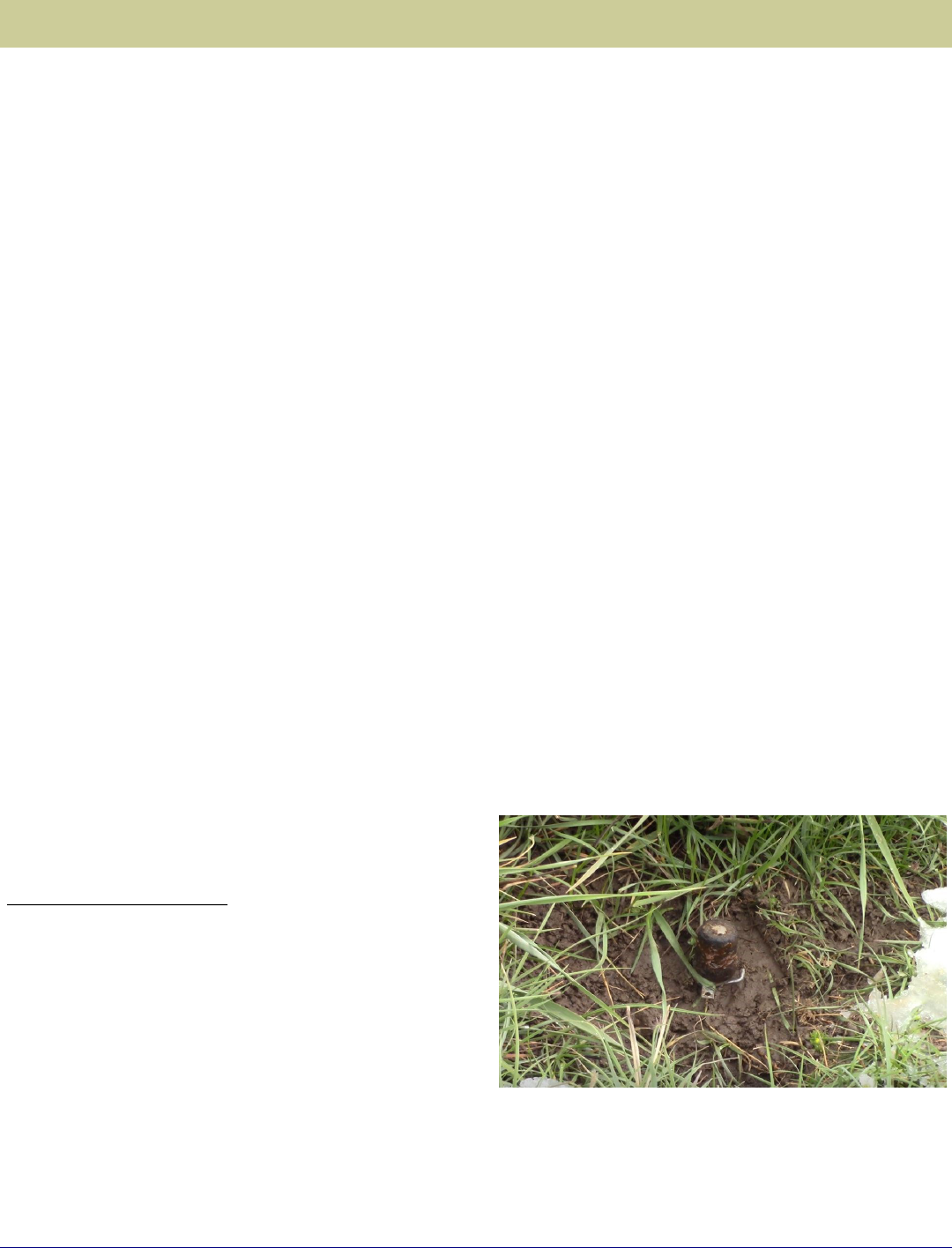

Figure 3. Good animal husbandry practices, such as penning sheep at night and properly burying or disposing of livestock carcasses

(as shown),

can help prevent coyote depredation.

Page 6

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

helps to reduce coyote depredation. Confining livestock

entirely to buildings nearly eliminates coyote depredation,

though may be impractical in many situations.

Carcass Removal

The proper removal and disposal of dead livestock is

important since carcasses tend to attract coyotes and other

predators, and may result in habituation to that food source

(Figure 3). Coyotes are attracted to easily accessible carrion

and, as a result, depredation losses to nearby livestock can

be higher.

Pasture Selection

Habitat features often change with seasonal crop growth.

Harvested or cultivated fields are often void of coyotes during

winter but provide cover for them during the spring through

fall growing season. This may lead to a corresponding

increase in depredation on nearby livestock.

Livestock in remote or rugged pastures are usually more

vulnerable to coyote depredation than those in closer, more

open, and smaller pastures. A relatively small, open, tightly-

fenced pasture that can be kept under close surveillance is

generally a good choice for birthing livestock, if lambing sheds

are unavailable. Also consider previous coyote presence in the

area, as well as weather and disease issues.

At times, coyotes kill in one pasture and not in another.

Changing pastures during these times of loss may reduce

depredation. Pasture features, like slope, rough or broken

terrain, brushy cover, and lack of human activity, provide ideal

conditions for coyotes. Pastures adjacent to streams, creeks,

or rivers may be more prone to coyote activity since water

courses serve as coyote hunting and travel corridors.

Herders/Shepherds

Using herders or shepherds to watch over livestock in large

pastures can help reduce coyote depredation. If herders are

not used, daily or periodic checks on the livestock is a good

animal husbandry practice.

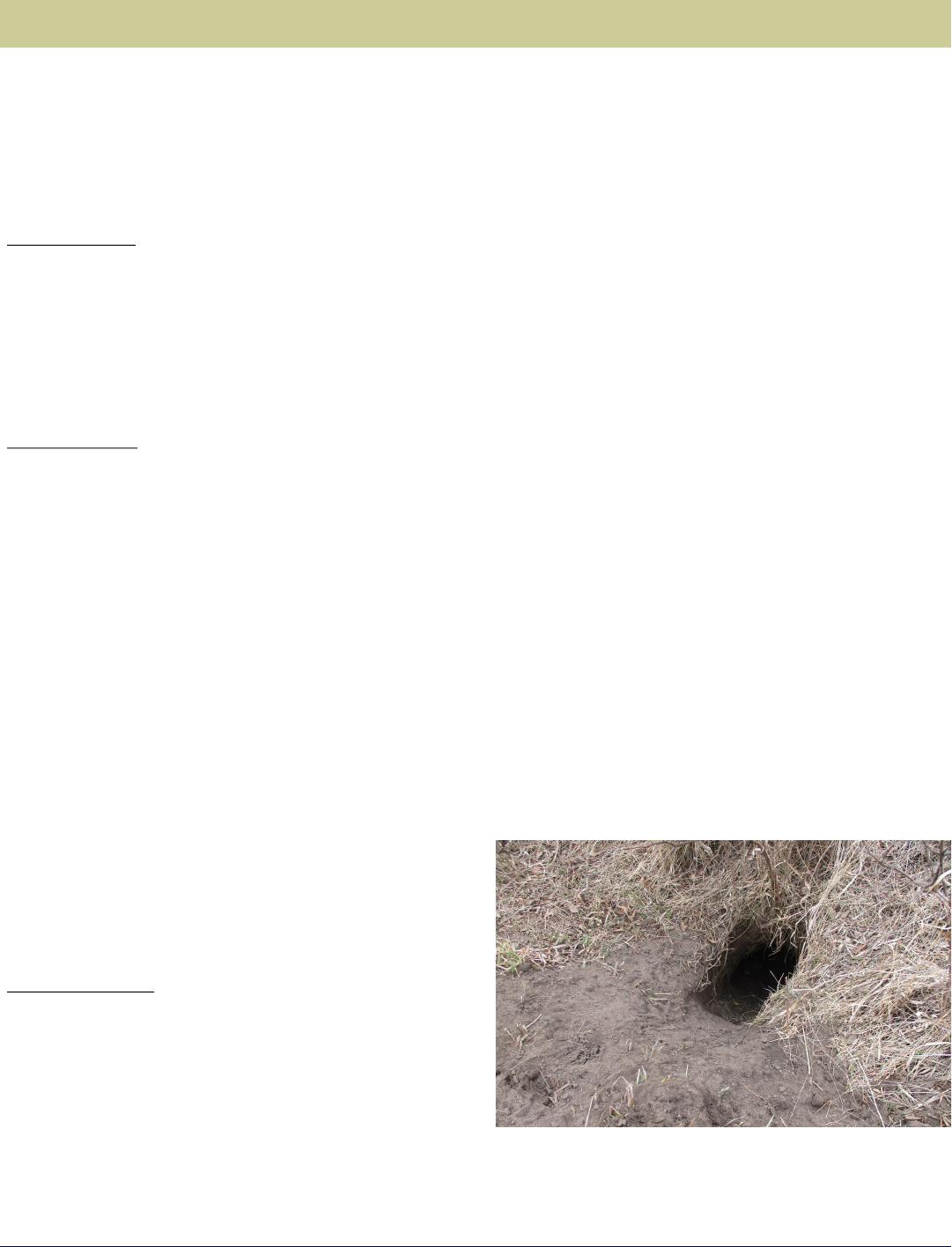

Denning

Coyote depredation can be reduced by locating coyote dens

(Figure 4) and lethally removing the adults and young of the

year (known as denning). Denning is prohibited in some

areas. Check local and state regulations and restrictions.

Denning may be warranted as a preventive control strategy if

coyote depredation historically or consistently occurs in a

particular area. Although denning requires special skills,

training, and considerable time, the advantages can be

significant.

Mated coyote pairs are extremely protective of their territory

when raising young and will vigorously defend it from other

coyotes. Coyotes often den year after year in the same

general location. If a particular denning pair of coyotes has a

history of existing with and not preying on livestock, it may be

advantageous to leave them alone. Their removal will open

up a territory that may become occupied with coyotes that

could prey on livestock.

Tracking a coyote from a kill site back to its den is one

method for locating a den site. This can be done by patiently

observing from a distant vantage point. A trained trailing

hound also may be useful for this task. If the general area of

the den is known, use a predator call to imitate a coyote howl.

This usually solicits a response from any nearby coyote and

helps determine the den’s location.

Figure 4. Coyote den.

Aircraft can be used to locate coyote dens when

depredations occur in spring or early summer. Dens are

most easily located after young of the year begin venturing

outside the burrows. Flattened vegetation around the den

site can make it more visible from the air. If legal at the

location, the coyotes can be lethally removed through

aerial operations; otherwise, note the location and return

on foot or by vehicle.

Once the den is located, approach the den unseen and

downwind to within calling distance. A call that imitates the

distress whine of a young coyote can draw out the adults,

especially when used in conjunction with a specially-

trained dog to act as a lure/decoy. The sound of a young

coyote in distress, along with the sight of a dog near the

den causes most coyotes to display highly aggressive

behavior, frequently chasing the dog and coming out into

the open where they can be lethally removed with a

firearm. After the adults are removed, a trained applicator

can fumigate the den with a large gas cartridge registered

for this purpose (see Fumigants).

Exclusion

New materials and designs have made fences an effective

and economically practical method for preventing coyote

access to pastures, airport environments, backyards, and

other areas. However, many factors, including the density,

behavior and motivation of coyotes, terrain and vegetative

conditions, availability of other prey, size of pastures, and

time of year, as well as the fence design, construction, and

maintenance, will impact the overall effectiveness of a

fence.

It is unlikely that fences will totally exclude all coyotes from

an area, especially large areas or ranges; however, fences

can increase the effectiveness of other damage

management methods, such as penning livestock, using

guard animals, and trapping. For example, the combined

use of livestock protection dogs (LPD) and fencing

sometimes achieves a greater degree of success than

either method alone. An electric fence may help keep an

LPD in and coyotes out of a pasture. If an occasional

coyote passes through the fence, the LPD can keep it away

from the livestock and alert the producer by barking.

Fencing can concentrate coyote activity at specific locations,

such as gateways or ravines, that coyotes use to easily gain

access to livestock. Set foothold traps and cable devices at

strategic locations along a fence to effectively capture

coyotes.

While beneficial for livestock, fences can pose problems for

wildlife. In particular, barrier fences may exclude not only

coyotes, but also many other wildlife. Special attention

should be made where fencing intersects wildlife travel or

migration corridors.

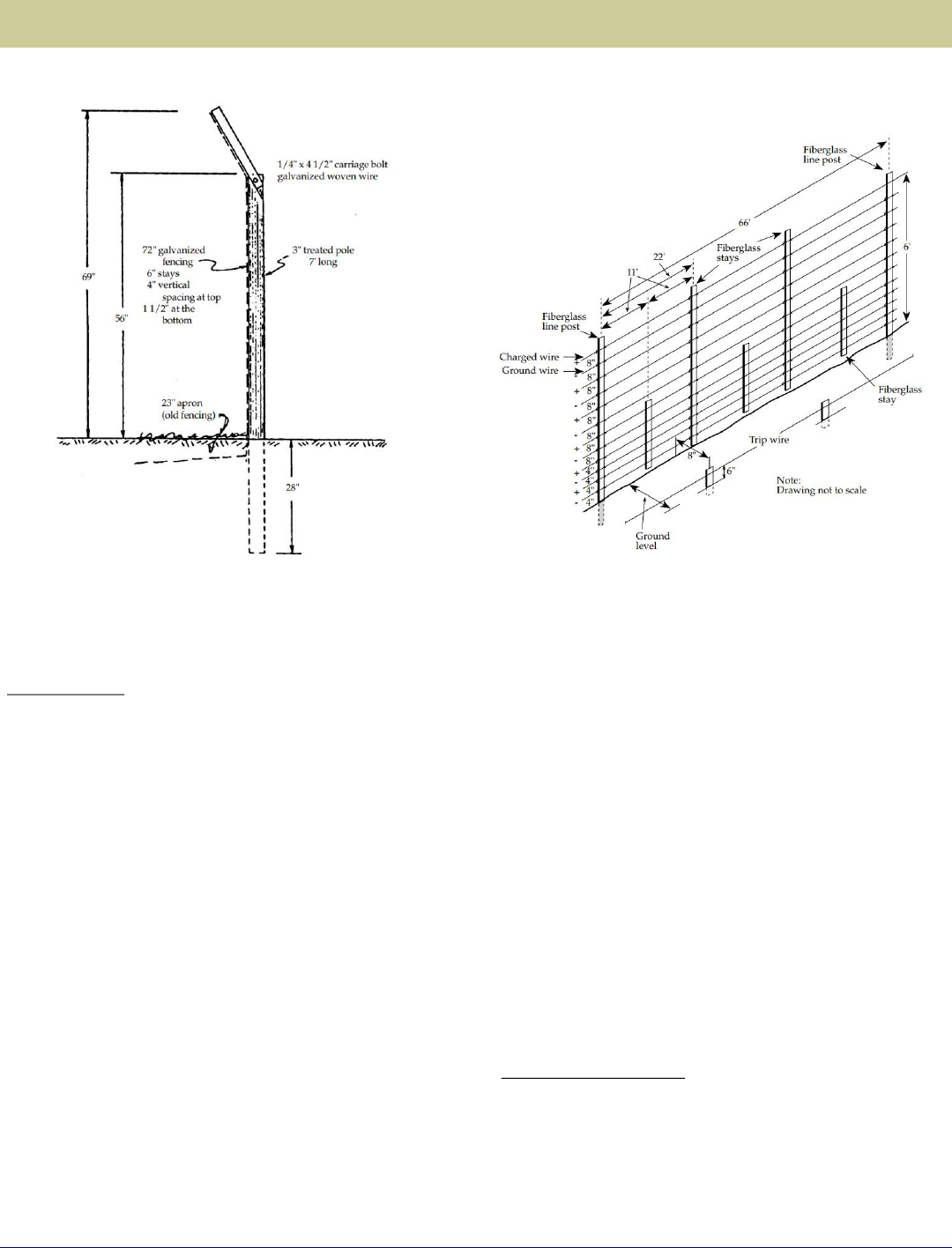

Net-Wire Fencing

Well maintained net-wire or barrier fences deter many

coyotes from entering a pasture. Horizontal spacing of the

mesh wire should be less than 6 inches (15 cm), and vertical

spacing less than 4 inches (10 cm). Digging under a fence

can be discouraged by placing barbed wire at ground level or

using a buried wire apron. A fence at least 5.5 feet (ft) (1.6

meters (m)) high will keep coyotes from jumping over it.

Climbing can usually be prevented by adding an electrified

wire at the top of the fence or installing a barbed wire

overhang (Figure 5).

The construction and materials for such fencing can be

expensive. Therefore, fences of this type are rarely used

except around small pastures, corrals, feedlots, or areas used

for temporary confinement.

Page 7 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Page 8

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Electric Fencing

Modern electric fencing for livestock containment and

exclusion often is constructed of stretched, smooth, high-

tensile steel wire and has chargers that maintain high

output with low impedance which resists grounding and

minimizes fire hazards.

Many electric fence designs charge every wire. A charged

tripwire can also be installed just above the ground about 8

inches (20 cm) outside the main fence to discourage digging

by animals (Figure 6).

Electric fencing is easiest to install on flat or even terrain.

Labor to keep electric fencing functional can be significant

and includes:

• Maintaining wire tension;

• Removing excessive vegetation under the fence to

prevent grounding;

• Repairing damage from livestock or wildlife;

• Regularly checking the charger to ensure it is operational;

and

• Checking for trapped animals inside the fence. These

animals receive a shock as they enter the pasture and

may subsequently avoid approaching the fence to

escape.

In situations where conventional fencing is in good condition,

adding 1 or 2 charged wires can significantly enhance

predator deterrence. A charged wire placed 6 to 8 inches (15

to 23 cm) above the ground at 8 to 10 inches (20 to 25 cm)

outside of the fence can help to prevent digging by animals. If

coyotes are climbing or jumping a fence, add charged wires

to the top or at horizontal levels above the ground. Wires

should be offset and outside of the fence.

Portable Electric Fencing

The advent of safe, high-energy chargers (battery or solar-

powered) has led to the development of portable electric

fences. Electric fencing is created with thin strands of wire

Figure 6. High-tensile electric fence.

Figure 5. Barrier fence with wire overhang and buried apron.

running through polyethylene twine or ribbon, called poly-wire

or poly-tape. The poly-material is available in single and

multiple wire rolls or as a mesh fence of various heights. It

can be quickly and easily installed to serve as a temporary

corral to avoid depredation at places or periods of high risk

(i.e., at night), to partition off pastures for controlled

grazing, or to protect threatened or endangered species

nesting sites (e.g., sea turtles, piping plovers) from

depredation. Note that range livestock that are not

accustomed to being fenced may be difficult to contain in a

portable fence.

Corrals

Confining livestock in a corral at night helps to reduce

depredation. Adding light, noise, and using an enclosure with

good structural integrity also increases the effectiveness of

corrals. Keeping livestock penned on foggy or cloudy days

may be helpful, as coyotes seem to be more active under

those conditions.

The potential downsides of using corrals include building

costs and labor, herding, and feeding livestock. Additionally,

confined livestock may increase parasite and disease

problems within the flock or herd.

Fertility Control

No fertility control agent is currently available for use with

coyotes. Past research on fertility control (e.g., sterilization,

reproductive inhibitors, and chemical treatments) reveals

some success in reducing coyote depredation, as treated

territorial pairs no longer need to provide for young of the

year. However, the costs may be limiting, and in some

cases, annual treatment is required. These methods

remain an area of research, but may not be practical nor

effective on coyote populations.

Frightening Devices

Coyotes are often suspicious of novel stimuli and frightening

devices are most useful for reducing coyote damage during

short periods of time. Avoid acclimation by varying the

position, appearance, duration, or frequency of the

frightening stimuli, or using them in various combinations.

A variety of frightening devices and equipment exists,

including animated scarecrows, fladry, lights and alarms,

and propane cannons. Many are battery powered, motion-

activated or programmable, and provide a variety of

sounds or lights to frighten coyotes from the protected

area.

Bells and Radios

Some livestock producers place bells on some or all of

their livestock to discourage predators. Livestock are easily

located, and the unnatural or unfamiliar sounds associated

with them may discourage predators. A radio tuned and

playing a 24-hour station may be a temporary deterrent in

smaller penned areas or enclosures.

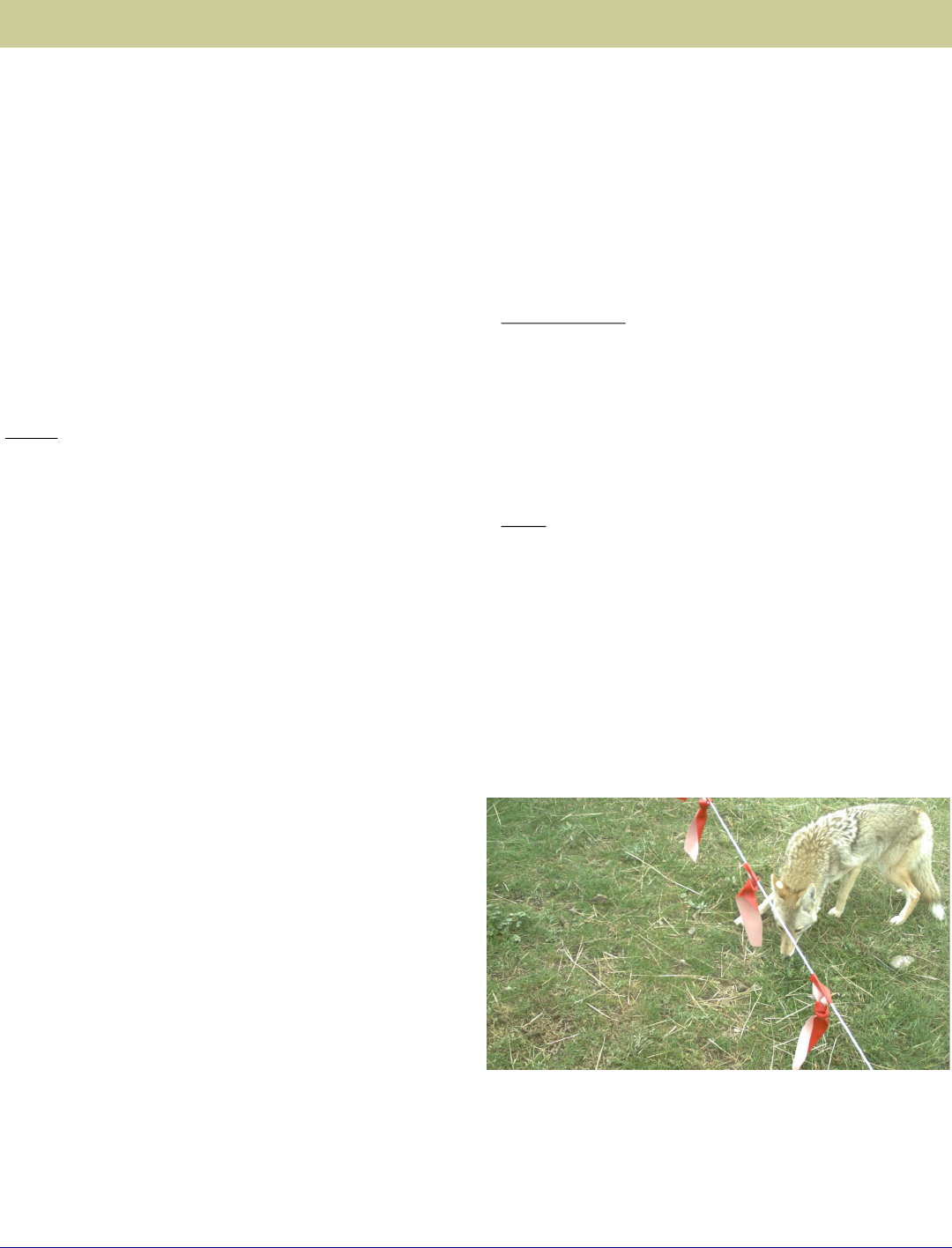

Fladry

Fladry consists of a line of brightly colored flags hung at

regular intervals along the perimeter of a pasture. For extra

protection, the line carrying the flags can be electrified,

which is known as “turbofladry.”

Because carnivores are often wary of new items in their

environment, like fluttering flags, they are cautious about

crossing the fladry barrier—at least for 3 to 4 months. That

Page 9 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Figure 7. A 2019 USDA study showed fladry made with the top-knot design

(shown)

and

with flags spaced 11 inches (27.9 cm) apart was the most effective at preventing

coyotes from crossing a fladry barrier.

Page 10

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

added time of protection may be enough to protect calves

and lambs during critical periods. The effectiveness may

be short-lived for coyotes as they are quite adaptable to

this type of novel stimuli. A 2019 USDA Wildlife Services

study showed fladry made with a top-knot design and with

flags spaced 11 inches (27.9 cm) apart was the most

effective at preventing coyotes from crossing a fladry

barrier (Figure 7).

Lights

Lighting can act as a deterrent to coyotes, particularly in

confined areas, such as corrals. Use daylight sensors or

timers to activate the lights and reduce electricity costs.

Revolving, flashing, or strobe lights with motion detectors may

enhance their effectiveness.

Propane Cannons

Propane cannons produce loud discharges at timed intervals

when a spark ignites a measured amount of propane gas. On

most models, the time between discharges can vary from 1

to 55 minutes. Their effectiveness at frightening coyotes is

usually temporary, but it can be increased by moving

cannons to different locations every 3 to 4 days, varying the

intervals between discharges, and using them in conjunction

with other frightening devices. In pastures, propane cannons

should be placed on rigid stands or T-posts. Elevated propane

cannons reduce the potential for rodent infestations in the

equipment that could cause malfunctions. Cannons can be

fitted with timers to allow them to come on at predetermined

times (e.g., before dark and at daybreak). Depending on

location especially in relation to neighbors, noise may be a

consideration.

Scarecrows

Scarecrows, air dancers or similar erect figurines may be

effective predator frightening devices for short periods of

time. Adding movement to the figurine increases its

effectiveness. Air dancers with supplemental lighting may

be useful as nocturnal frightening devices.

Strobe Lights and Sirens

The USDA Wildlife Services program developed a frightening

device called the Electronic Guard (EG) (Figure 8). The EG

consists of a strobe light and siren controlled by a variable

interval timer that is activated at night with a photoelectric

cell. In tests conducted in fenced pastures, EGs reduced

depredation by approximately 89 percent. Most research on

the effectiveness of EGs has been done with sheep

operations. EG use differs for pastured versus ranged sheep

operations. Although EGs are no longer manufactured by

USDA Wildlife Services, similar devices are sold by private

companies. Tips for using the EG and similar devices with

fenced and pastured sheep include:

• Placing devices above the ground on fence posts, trees,

or T-posts so they can be heard and seen at greater

distances and to prevent livestock from damaging them;

• Positioning devices so that rainwater cannot enter the

device and cause a malfunction;

Figure 8. Strobe lights and sirens, such as those used in an Electronic

Guard

(shown)

and similar devices, reduce livestock depredation

during short periods of time and have little to no negative impacts on

livestock behavior.

• Positioning devices so that light can enter the photocell

port or window. If positioned in deep shade, the device

may not turn on or off at the desired times;

• Using at least 2 units in small (<30 acres/12 ha), level,

short-grass pastures; 3 to 4 units in medium (<100

acres/40 ha), hilly, tall grass, or wooded pastures; and

4 to 8 units in larger pastures (>100 acres/40 ha) where

livestock congregate or bed; and

• Placing devices on high spots, where depredation has

occurred, at the edge of wooded areas, near or on

bedding grounds, or near suspected coyote travel

corridors. The devices should be moved to different

locations every 10 to 14 days to reduce acclimation.

The number of devices used in open range situations

depends on the number of livestock and size of their bedding

grounds. Herders who bed their livestock tightly have better

results than those who allow bedding over large areas. Tips

for using the devices with open range or herded livestock

include:

• Using 4 EGs in bedding areas to protect herds of 1,000

head and their young;

• When possible, placing an EG in the center of the

bedding ground and others around the edge. Try to place

the units in suspected coyote travel corridors; and

• Placing EGs on high points, ridge tops, edges of

clearings, or on high rocks or outcroppings. Hang the

devices on tree limbs 5 to 7 ft (1.5 to 2.1 m) above

ground level. If used above timberline or in treeless

areas, hang them from a tripod of poles.

Vehicles

Coyotes associate vehicles with human activity. Parking cars

or pickups in areas where losses are occurring may

temporarily reduce depredation. Effectiveness can be

improved or extended by frequently moving the vehicles to

new locations.

Guarding Animals

The use of guarding animals, such as dogs and donkeys, to

protect flocks and herds from predators is a common

nonlethal predation damage management tool.

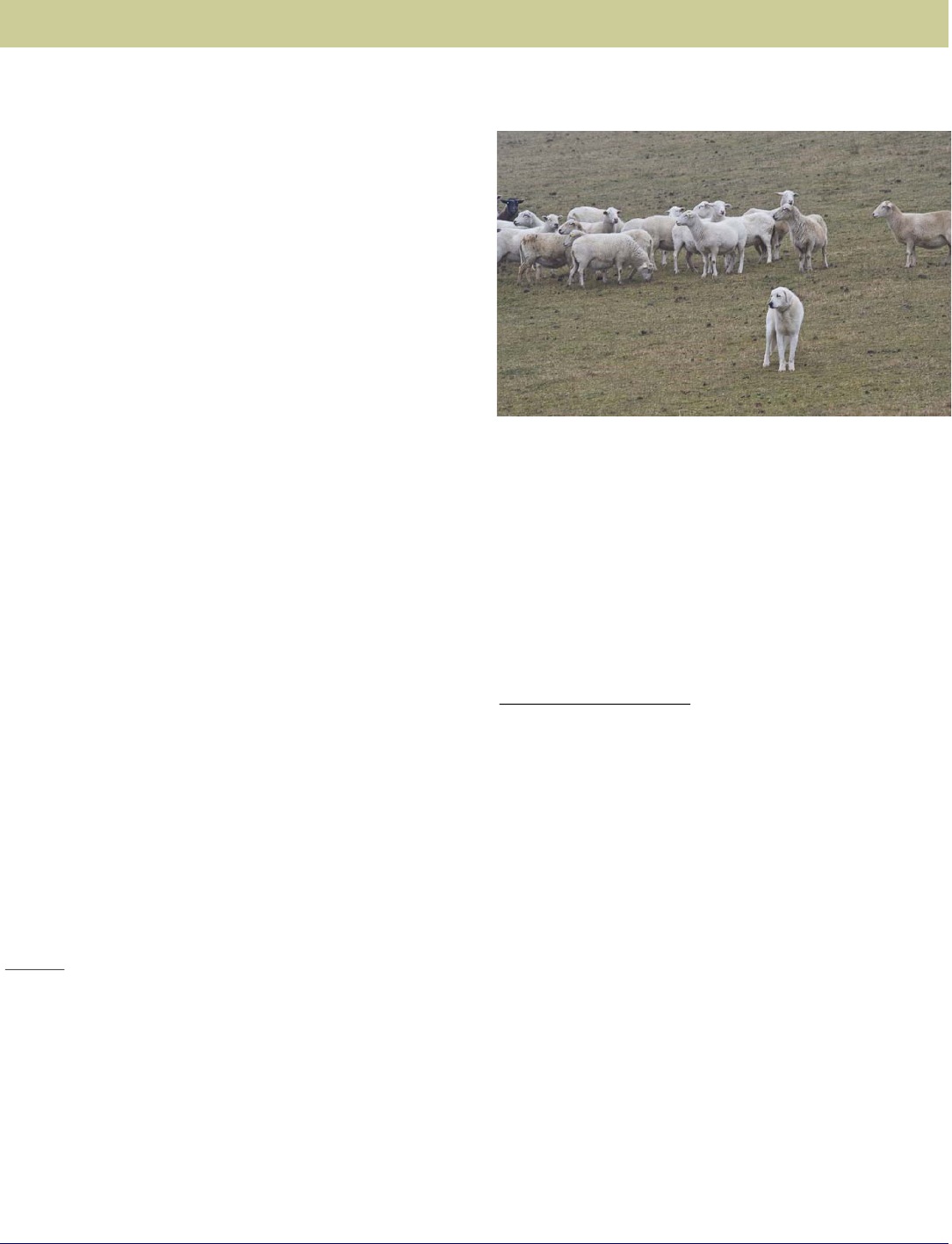

Livestock Protection Dogs

Livestock protection dogs (LPDs) have been used for

centuries to protect livestock, primarily domestic sheep,

from large carnivores (Figure 9). LPDs are raised and

trained to stay with livestock without harming them. Their

protective behaviors are largely instinctive, but proper rearing

plays a part. LPDs should be acquired from a trained,

reliable, and professional breeder.

Breeds commonly used as LPDs include the Great Pyrenees,

Komondor, Anatolian Shepherd, and Akbash. Other Old-World

breeds include Maremma, Sharplaninetz, and Kuvasz. LPDs

typically live for about 10 years. Mixed breeds may be

developed to provide for certain traits or needs.

USDA Wildlife Services research on the use of three larger

European LPD breeds (Portuguese Transmontanos, Bulgarian

Karackachans, and Turkish Kangals) to prevent depredation

by predators larger than a coyote, such as grizzly bears and

Page 11 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Figure 9. Livestock protection dogs (LPDs) have been used for centuries to protect

livestock from predators.

Page 12

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

wolves, determined that all the breeds successfully,

protected sheep, but showed different guarding traits

and behaviors. Producers may want to balance the traits of

multiple dog breeds by having some that prefer to stand

guard with the flock and some that seek out and

investigate potential threats.

The characteristics of each livestock operation dictates the

number of dogs required for effective guarding. If coyotes are

scarce, one dog is sufficient for most fenced pasture

operations. Range operations often use two dogs per herd of

livestock. The performance of individual dogs differs based

on age and experience.

Coyote density, as well as the size, topography, and habitat of

the pasture or range must also be considered. Relatively flat,

open areas can be adequately covered by one dog. When

brush, timber, ravines and hills are in the pasture, several

dogs may be needed, particularly if the livestock are

scattered. Livestock that flock and form a cohesive unit,

especially at night, can be protected by one dog more

effectively than livestock that are scattered and bedded in a

number of locations.

Donkeys

Donkeys or burros are generally docile to people but seem to

have an inherent dislike for dogs and other canids. The

typical response of a donkey to an intruding canid may

include braying, bared teeth, a running attack, kicking, and

biting. Pasturing a donkey with sheep, goats or other

compatible livestock can help reduce coyote depredation.

Donkeys are less expensive to obtain and care for than

LPDs, and may be less prone to accidental death and

premature mortality. An average lifespan for a donkey is 33

years. Donkeys can be used with relative safety in

conjunction with other damage management tools, such as

cable devices, foothold traps, and toxicants.

For more information about donkeys, see Appendix II.

Llamas

Like donkeys, llamas have an inherent dislike of canids, and

a growing number of producers are using llamas to protect

their livestock. Llamas bond with sheep or goats within hours

and offer advantages over guarding dogs similar to those

described for donkeys. The average lifespan for a llama is 20

years.

Other Animals

Any animal that displays aggressive behavior toward intruding

coyotes may offer some benefit in deterring depredation.

Other animals reportedly used for reducing depredation

include mules, ostriches, and larger breeds of goats.

The USDA Wildlife Services program tested whether the

bonding and pasturing of sheep and goats with cattle helped

to protect them from coyote depredation. Results showed the

sheep and goats that remained near cattle did receive some

protection. Whether this protection was the result of direct

actions by the cattle or by the coyotes’ response to the cattle

is uncertain. Multi-species grazing allows for optimal foraging

practices and may also help reduce coyote depredation.

Habitat Modification

Modify habitats to eliminate or reduce areas that provide

cover, resting habitat, or travel corridors for predators.

Prevent prey species, such as deer, pheasants, rabbits, or

turkeys from gathering too close to human habitation or

with livestock. Completely remove dead animal carcasses

from pastures or bury them deep in place.

Hazing

Hazing (i.e., scaring) coyotes involves people yelling,

throwing objects or aggressively approaching individual

coyotes more frequently so that coyotes retain or gain

more fear of people. It is commonly promoted as a

nonlethal method to reduce urban coyote conflicts. USDA

Wildlife Services’ studies with captive coyotes suggest that

hazed coyotes learn to avoid behaviors, such as getting too

close to people, that might result in more hazing.

Additionally, coyotes that were fed or followed by a dog

were more likely to approach a person even if it resulted in

hazing. Coyote hazing can work in certain situations, but

researchers note a coyote’s past experiences with people

influences the technique’s effectiveness.

Coyotes can be called at any time of the day, although shortly

after dawn and just before dusk are usually best anywhere

they are present. Night and thermal vision optics may extend

predator calling opportunities after dark. Some coyotes come

to a howl without howling back.

Night Operations

Shooting coyotes at night using thermal vision, night vision,

or artificial light may be effective. This technology may also be

useful for observing coyote behavior at night.

Review all local restrictions or regulations concerning

discharging a firearm during hours of darkness and the use of

thermal or night vision equipment. Seasonal restrictions or

requirements may also exist if night operations are conducted

during regulated harvest seasons.

For safety reasons, areas targeted for night operations should

be scouted in advance during daylight. Create range maps

with determined distances, locations of occupied or

unoccupied structures, or terrain features that may hide an

advancing coyote. Take special note of penned or pastured

livestock, or the presence of domestic canines. Be familiar

with the equipment and able to accurately identify coyotes

during hours of darkness.

Aerial Operations

The use of aircraft for shooting coyotes is regulated by the

Airborne Hunting Act and is allowed under special permit in

states where legal. Aerial operations are very selective,

allowing for the removal of targeted species. It is an effective

alternative for removing coyotes that have evaded other

methods, such as trapping.

Fixed-wing aerial operations is limited primarily to open areas

with little vegetative cover. Due to their maneuverability,

helicopters are more effective for shooting in areas of brush,

scattered timber, and rugged terrain.

Although aerial operations can be conducted over bare

ground, it is most effective with snow cover. Coyotes are

more visible against a background of snow than green or

brown vegetation. Their tracks are also more visible in the

snow. Flying a grid pattern ensures areas are not missed.

Page 13 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Repellents

No effective chemical repellents are available to repel

coyotes.

Relocation

Capturing and moving animals (also known as relocation)

is rarely legal nor is it considered a viable solution by

wildlife professionals for resolving certain wildlife damage

problems. Reasons to avoid relocating wildlife include legal

restrictions, disease concerns, liability issues associated

with injuries or damages caused by a relocated animal,

stress to the animal, homing behavior, and risk of death to

the animal. Check state and local regulations before

considering relocation.

Shooting

Shooting is a common method for lethally removing coyotes.

Safety is a critical factor and may preclude the use of

firearms due to local laws or human habitation. Consider all

available management options and proceed accordingly.

The choice of firearm, caliber, and bullet will vary based on

circumstances in the field. For instance, distance to target is

important in the selection of the appropriate firearm

(shotgun or rifle). The accuracy of firearms may be enhanced

with accessories, such as night vision, illuminated or fiber

optic sights, adjustable trigger assemblies and stocks, and

tripods or shooting stands.

Predator Calling

Predator calling is used to locate coyotes or draw them close

for shooting purposes. Common sounds used in predator

calling replicate coyote howling, young coyote whining or

distress sounds, and prey animal (cottontail, jackrabbit, bird,

or young ungulates) distress sounds.

Predator calls can be hand-held and mouth-blown reed calls,

or recorded sounds amplified through a battery-operated

player and speaker. Advances in recording and player

technology have allowed for remote use, and the opportunity

to select from a variety of stored recordings that create

realistic sounds.

Page 14

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Aerial crews generally fly the grid with the sun at their

backs, allowing the sunlight to highlight coyotes and other

ground features.

A ground crew assists with aerial operations. Before the

aircraft arrives, the ground crew often works to locate coyotes

in the area by eliciting howls. Two-way radio communication

allows the ground crew to direct the aircraft toward the sound

of the coyotes, thus reducing search times.

Aerial operations require special skills and training for both

the pilot and gunner. Weather, terrain, and state or local laws

limit the application of this method.

Toxicants

Pesticides are an important component in integrated wildlife

damage management and their use is regulated by federal

and state laws. All pesticides used in the United States must

be registered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) under the provisions of the Federal Insecticide,

Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, as well as the appropriate

state agency. Registered pesticides must be used in

accordance with label directions. Some pesticides can only be

applied by persons who have been specially trained and

certified for their use. Each of the chemical methods listed

below have specific requirements for their handling, transport,

storage, application, and disposal.

Three toxicant active ingredients and eleven end-use products

are registered with the EPA for use with coyotes to reduce

predation.

Sodium Cyanide and the M-44

Sodium cyanide is used in the M-44 ejector device (EPA Reg.

Nos. 56228-15, 35978-1, 35975-2, 39508-1, 33858-2, and

13808-8; products are all named M-44 Cyanide Capsules).

EPA Reg. No. 56228-15 can only be used under the

supervision of the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection

Service (APHIS), and EPA Reg. Nos. 35978-1, 35975-2,

39508-1, 33858-2, 13808-8 can only be used under the

supervision of the state’s department of agriculture.

The M-44 is a spring-activated device that delivers a dose

of sodium cyanide powder from the cyanide capsules to a

coyote. All six M-44 cyanide capsule products are

registered as Restricted Use Pesticides (RUP) by the EPA

and can be used only by specially trained certified

pesticide applicators who must comply with a number of

product-specific use restrictions designed to protect

people, domestic animals, and non-target wildlife.

The M-44 ejector device consists of four parts: a capsule

holder wrapped with cloth, wool, or other soft material; a

cyanide capsule (small plastic container holding less than

1 gram of sodium cyanide); a spring-activated ejector; and

a 5- to 7-inch tubular stake. In the field, the stake is

typically inserted with its top near the surface of the

ground (Figure 10). In specialized circumstances, the top

may be lower than the surrounding surface (i.e., the device

is set in a hole or depression) so as not to be stepped

upon, disturbed by large livestock, or seen by nontarget

scavenging birds. The cyanide capsule is inserted into its

holder and screwed onto the ejector. The ejector is placed

into the stake and secured. Specially formulated bait or

other attractant, which elicits a "bite and pull" response by

coyotes, is smeared on the wrapped capsule holder.

The M-44 device is triggered when a coyote bites and pulls

on the baited capsule holder, releasing the plunger and

Figure 10. The M-44 device is staked with its top placed near the surface of the

ground.

ejecting sodium cyanide powder into the coyote’s mouth.

The sodium cyanide quickly reacts with moisture in the

mouth, releasing hydrogen cyanide gas. Death is quick,

normally within 1 to 5 minutes after the device is triggered.

While the use of traps or cable devices may present a hazard

to livestock, M-44s can be used with relative safety in

pastures where livestock are present. M-44s remain

operational in adverse weather conditions like rain, snow, and

freezing temperatures.

Sodium Fluoroacetate and the Livestock Protection Collar

Sodium fluoroacetate (also known as Compound 1080) is

used in the Livestock Protection Collar (LPC) (EPA Reg. Nos.

56228-22, 39508-2, and 46779-1; products are all named

Sodium Fluoroacetate (Compound 1080) Livestock

Protection Collar). In Ohio, EPA Reg. No. 56228-22 can be

used only by USDA Wildlife Services applicators. EPA Reg. No.

39508-2 can only be used in New Mexico and EPA Reg. No.

46779-1 can only be used in Texas.

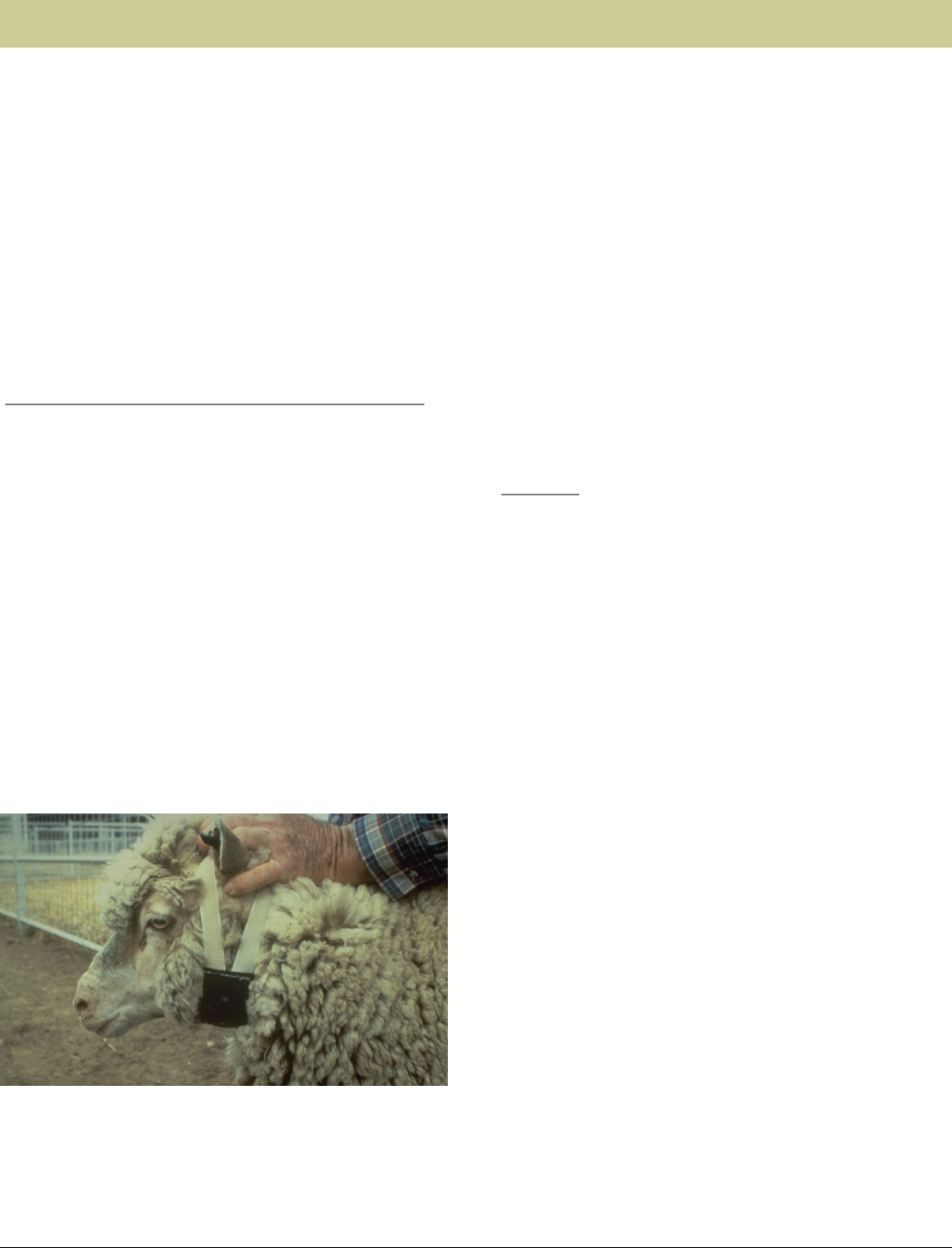

LPCs are worn around the necks of sheep or goats in a

group of animals experiencing predation. LPC products are

one of the most selective methods available to manage

coyote predation as only the coyote that attacks a sheep or

goat fitted with an LPC is killed (Figure 11). A coyote must

bite the prey animal on the neck and puncture one or both

sodium fluoroacetate reservoir bladders attached to the

collar to receive the toxicant. The sodium fluoroacetate is

ingested by the coyote and results in its death.

Typically, only operations with frequent or high depredations

justify the use of LPCs given the cost of the collars, sacrificed

livestock, and complying with use restrictions.

The LPC products are registered by the EPA as a RUP, and

certified applicators must be specially trained in their use.

Applicators must follow all label directions and Use

Restrictions contained in the LPC product’s accompanying

Technical Bulletin.

Fumigants

Large gas cartridges (EPA Reg. Nos. 56228-21 and 56228-

62) are products used for denning coyotes. The Large Gas

Cartridge (EPA Reg. No. 56228-62) can be used by any

person 16 years old or older. The APHIS-Only Large Gas

Cartridge (EPA Reg. No. 56228-21) can only be used by

trained USDA Wildlife Services applicators. Information on

registration status and availability of these products in

individual states may be obtained from the respective state’s

pesticide regulatory agency and from USDA Wildlife Services.

Large gas cartridges are registered, general use fumigant

products which contain 53% sodium nitrate, 28% charcoal,

and 19% inert ingredients to produce primarily carbon

monoxide along with other lethal gases in minor quantities

when ignited. A cartridge is lighted, placed as deep as

possible within the coyote den, and the den opening is sealed.

Death occurs when the lethal gasses are inhaled. Care

should be taken to plug dens with nonflammable material,

typically soil or rocks, to minimize the chance of nearby

grasses and leaf litter from catching fire. Gas cartridges

also may be used to euthanize coyotes that flee down a

hole during aerial operations.

Page 15 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Figure 11. The Livestock Protection Collar (LPC) is one of the most selective

methods available to manage coyote predation on sheep and goats—only the

coyote that attacks a sheep or goat fitted with an LPC is killed.

Page 16

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Trapping

Trapping describes foothold traps, cage traps, and cable

devices commonly used to capture coyotes. Foothold and

cage traps are designed to live-capture coyotes. Cable

devices are designed to either live-capture or lethally

remove coyotes.

Trapping rules and regulations vary by state. Consult local

laws and regulations prior to using any traps or cable

devices.

Trapper education programs exist in many states. This

training may be required prior to receiving a trapper’s

license and actively trapping. Check with the local state

agency for requirements and training opportunities. If none

exist, the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (AFWA)

and some states offer online training.

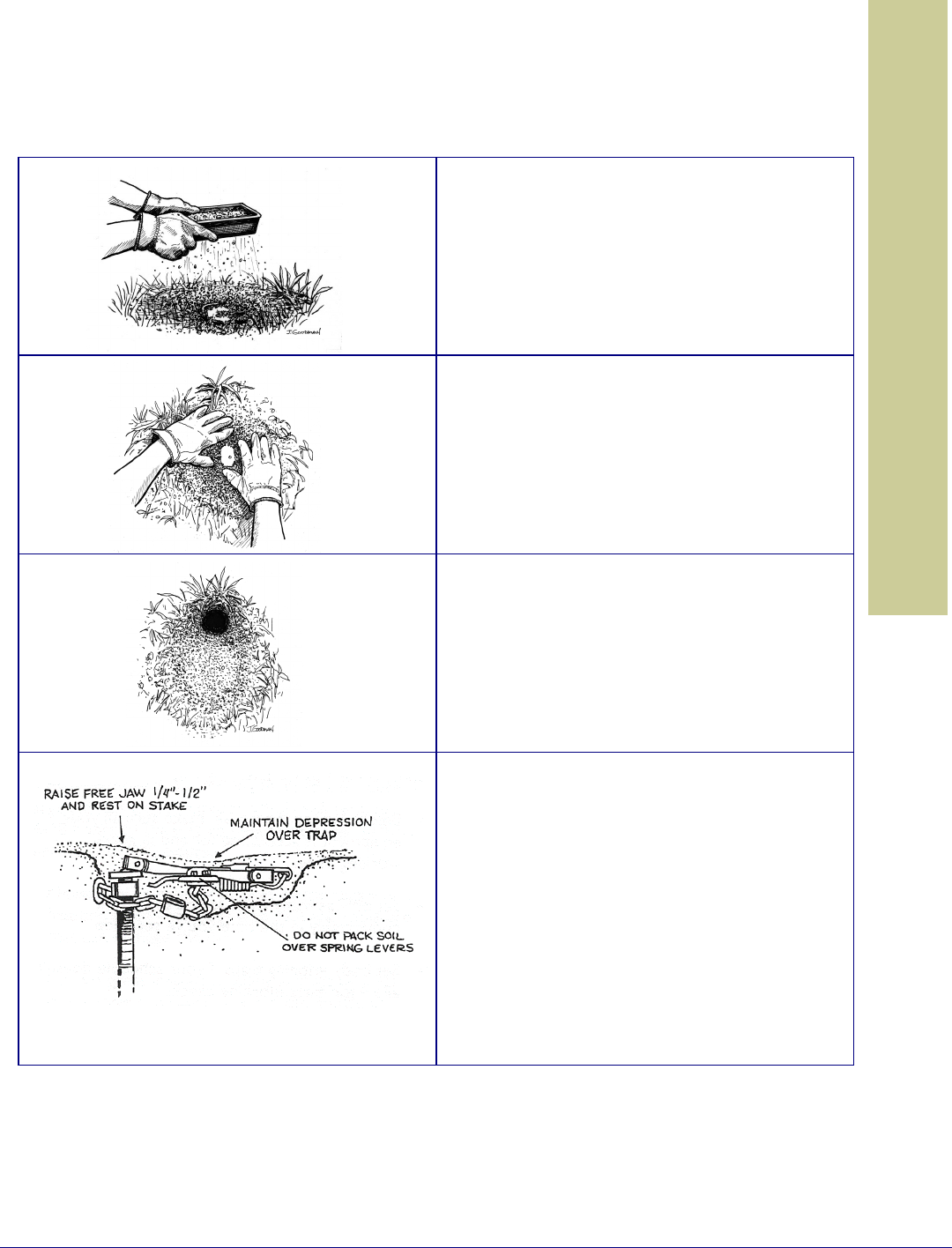

Foothold Traps

For more information on the use of foothold traps, please

see Appendix III.

Foothold traps should be purchased from reliable trap

manufacturers or supply outlets. Foothold traps for coyotes

vary in size and strength, allowing for use with different

sized animals (e.g., eastern coyotes [larger] versus western

coyotes) and environmental conditions (e.g., soil, moisture,

and temperature).

Common foothold trap sizes for coyotes range from #1½

(small) to #4 (large) and use either coiled springs or double

long springs. There are no manufacturing standards for

correlating these numbered foothold traps with their

dimensional measurements. Attributes like jaw spread,

spring strength, and stock nomenclature vary between

manufacturers. AFWA continues extensive research with

foothold traps, using criteria to measure the effects on

animal welfare, selectivity, efficiency, practicality, and

safety. Refer to the guides Best Management Practices:

Trapping Coyotes in the Eastern United States or Best

Management Practices: Trapping Coyotes in Western

United States for recommended sizes and measurements

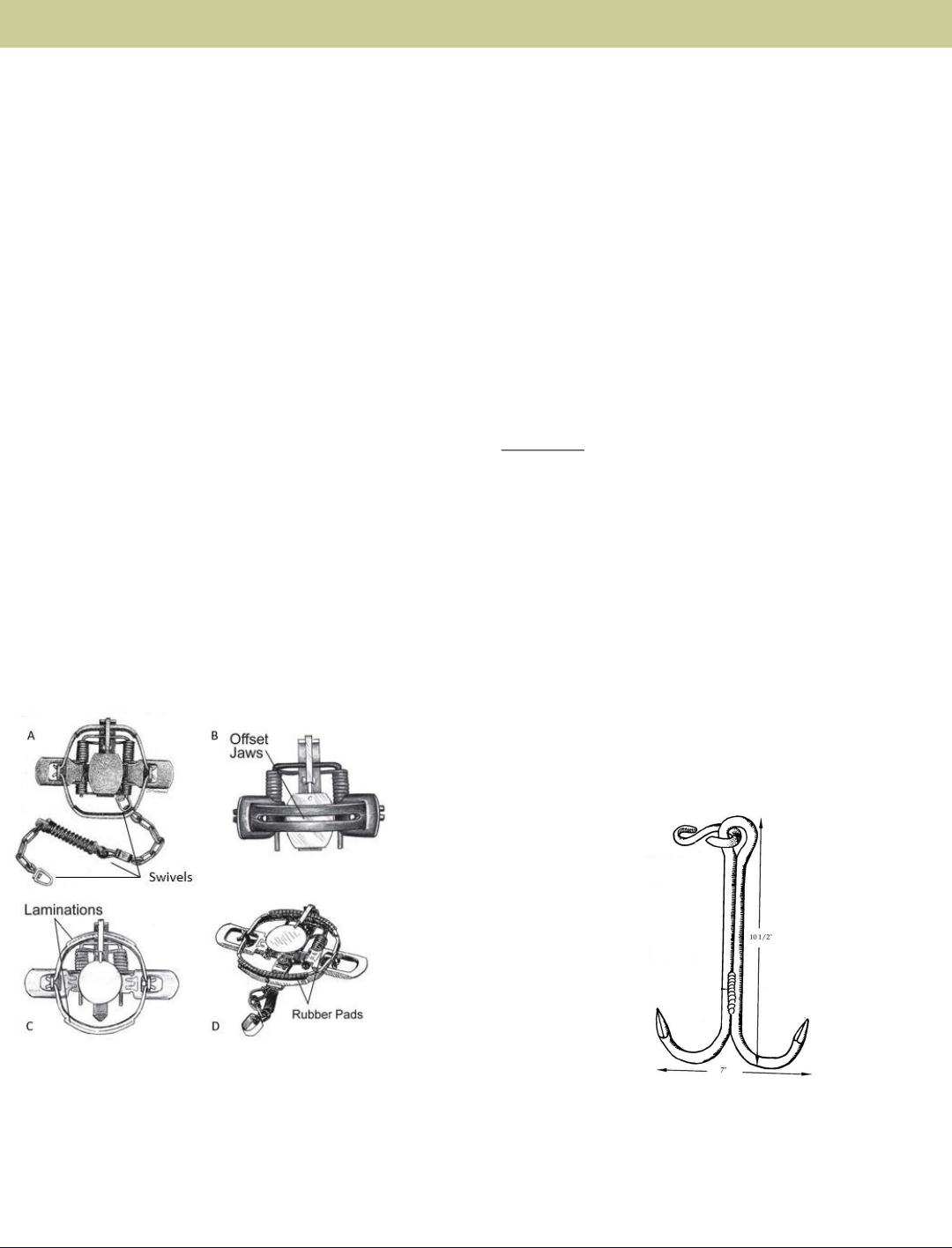

(Figure 12).

Coyotes are very strong, long legged, and often lunge while

restrained. Proper foothold traps for restraining coyotes

include the following characteristics:

• Offset, laminated, or padded jaws (Figure 13): Offset

jaws provide a space that allows for the mass of the

coyote’s foot. Offset and laminated jaws provide a

wider contact surface, which displaces the closing

pressure over a larger area. Padded jaws have a

replaceable rubber surface;

• 4 lbs (1.8 kg) of pan tension: Pan tension is measured

by applying a known weight to the trap pan to allow the

trap jaws to close. Using 4 lbs of pan tension allows

the foothold trap to be more selective for coyotes and

prevents smaller animals from being captured. It

increases the opportunity for a good foot pad catch

and reduces the potential for injuries and accidental

releases. Testing devices are commercially available

Figure 12. The Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies provides online

guides to best management practices for trapping.

from reliable trapping supply dealers. Pan tension is

typically increased or decreased by adjusting the nut

and bolt that attach the trap pan to the trap base

plate;

• An anchoring chain mounted to the center of the

foothold trap baseplate: Any pulling pressure applied

to the foothold trap is in direct line with the anchor.

This direct line reduces the potential for injury by

preventing the coyote’s restrained foot from sliding

between the foothold trap’s jaws;

• An anchoring chain with multiple in-line swivels:

Swivels allow the foothold trap to turn freely in any

direction and prevents binding which may cause injury

to the restrained foot; and

• An anchoring chain with a shock spring: A shock spring

lessens the impact of a sudden stop if a coyote lunges

while attempting to get free. Shock springs that can

handle 50 to 100 lbs (22 to 45 kg) of pressure are

typically used for coyotes.

Foothold traps set for coyotes are secured with a single

stake or double stake system; earth anchors; or drags

(Figure 14). The soil conditions generally determine what

anchoring system is used. Drags are typically used instead

of in-ground anchors in sandy or loose soils or to allow the

restrained coyote some movement to seek shelter.

Drags commonly use 6 to 10 ft (2 to 3 m) of chain between

the foothold trap and the drag. The drag and chain are

attached to the anchoring chain of the foothold trap. Drags

should be designed to leave marks or a trail so the

restrained coyote can easily be found.

Cage Traps

Cage traps used for coyotes should be at least 48 inches

(1.2 m) long, 16 inches (40 cm) wide, and 23 inches (58

cm) high. Darken the cage trap’s wire with paint or dye, use

vegetation to break up the outline of the trap, and line the

floor of the trap with dirt or vegetation to improve trapping

success. Pre-baiting the cage trap with common food items

which will be used during actual trapping may also help.

Encouraging a coyote into a cage trap is very difficult. Most

coyotes are wary of novel objects. Cage traps may be more

successful in urban or suburban environments where

coyotes are more accustomed to human activity and

human-made objects.

Page 17 U.S. Department of Agriculture

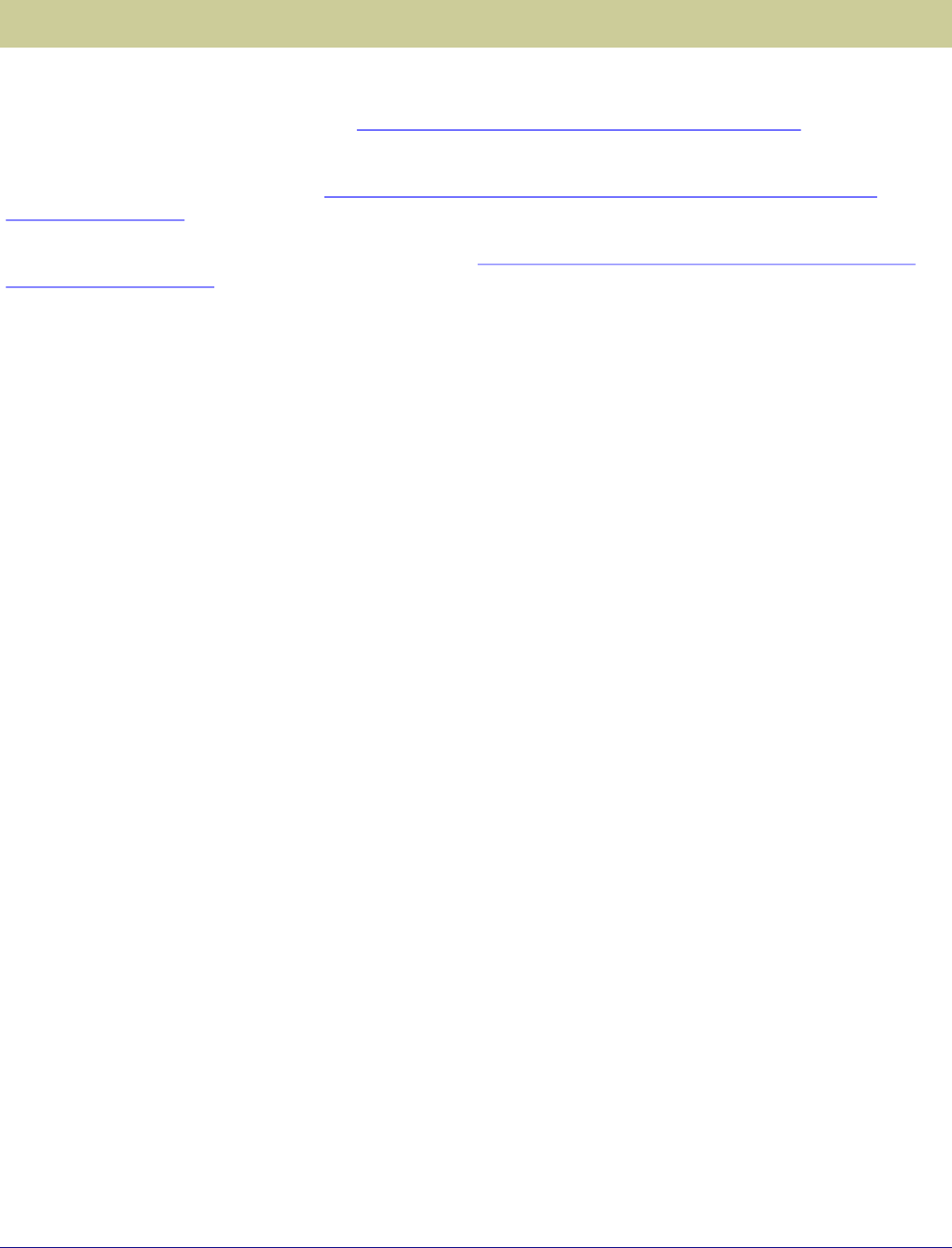

Figure 13. Foothold trap configurations: a) fully modified foothold trap

with center mounted anchoring chain, multiple swivels, and an in-line

shock spring; b) offset jaws; c) laminated jaws; and d) rubber padded

jaws.

Figure 14. A drag is often used when loose soil conditions prevent the use of in-

ground anchors

.

Page 18

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Cable Devices

For more information on the use of cable devices, please

see Appendix IV.

Cable devices (or snares) may be designed and set to

either live-capture or lethally remove coyotes.

Cable devices are not legal in all states. Where legal, states

may define the component requirements, measurements,

setting restrictions, and training requirements. Consult local

laws and regulations prior to using cable devices and acquire

legal cable devices from a knowledgeable and reliable

manufacturer. Carefully select sites where snares are set to

avoid capturing nontarget animals, such as dogs.

Unlike other capture tools, cable devices cannot be reused.

Once a capture is made, the stress applied to the cable

makes it unusable. Some cable device components may

be removed and re-used, but the cable itself cannot.

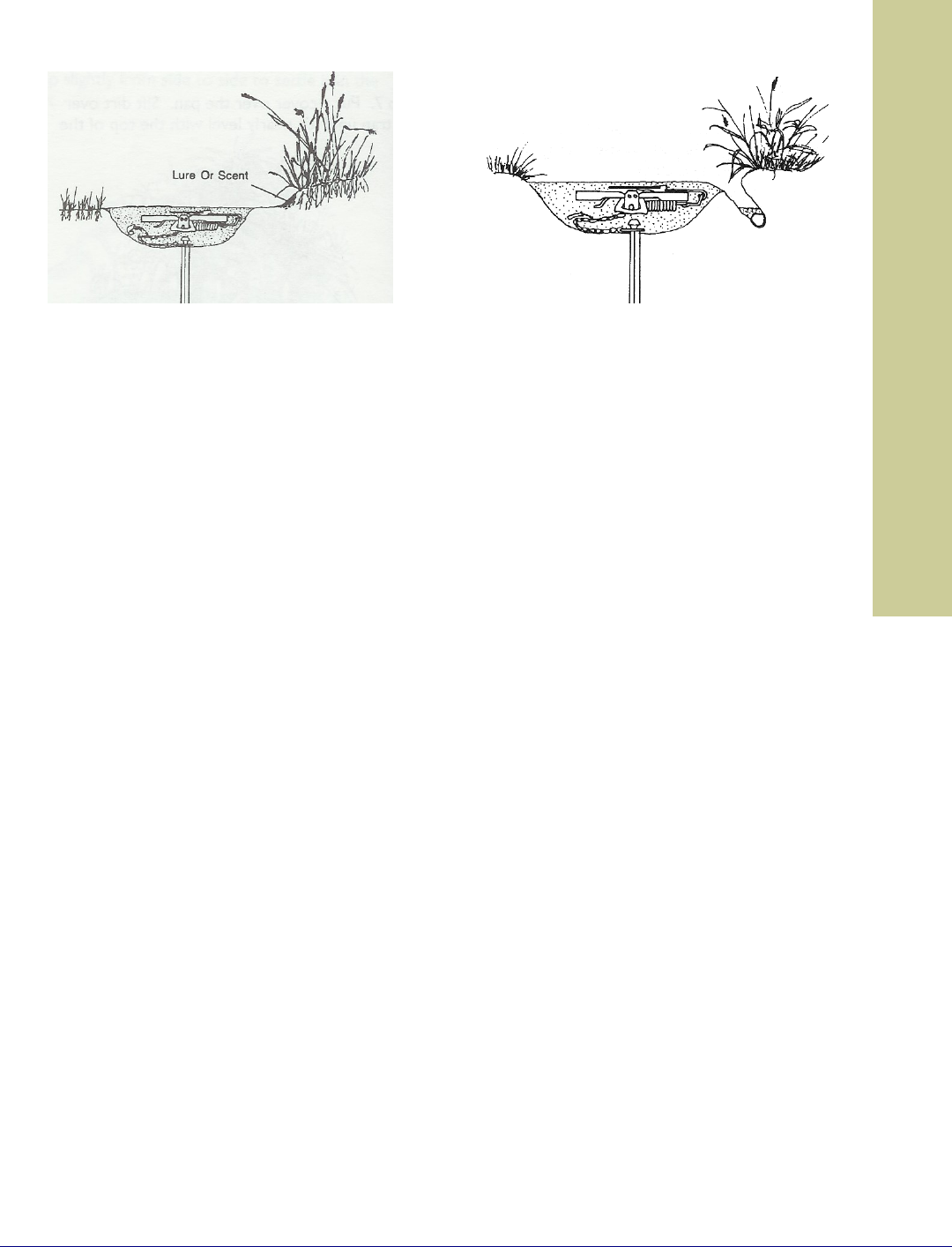

Cable devices are used to capture an unsuspecting coyote

as it is traveling on its commonly used trails (known as

“trailing”). Check the trail for recent tracks. If present,

place the cable device set where the trail narrows.

Approach the location from the side of the trail to prevent

unnecessary disturbance to the site. Position the cable

device’s loop in the center of the trail, so the coyote places

its head through it as it travels along the trail (Figure 15).

The support wire needs to hold the loop tightly and be

sturdy and stiff enough to handle wind and other weather

factors. Nine or 11 gauge wire is commonly used for

support wire (Figure 16). A moving cable device can easily

be detected by an animal or may cause the height and loop

size to change. A cable loop that has fallen may catch a

nontarget animal or may catch a coyote by the foot. Pay

attention to conditions that may change or alter the cable

devices and visit the sets regularly to check them.

Most cable devices are passive capture methods that are

only activated by an animal moving through the loop and

causing it to close. However, some systems are spring-

loaded. When an animal trips the trigger, a compressed

spring propels the cable loop around an animal’s foot or

neck (See Appendix IV). Spring-loaded foot cable devices

are commonly used in lieu of foothold traps in states where

foothold traps have been banned.

Avoid using lure or urine close to a cable device set, with the

exception of foot cable devices. Odors cause a coyote to

investigate, become cautious, or behave differently. The

coyote’s head will not be in line with the body, they may stop

or walk in circles to investigate, and depending on their

status in the area or experiences, they may leave.

Set locations should be on straight runs in the trail, not

curves or changes in direction. Look for a narrowing in the

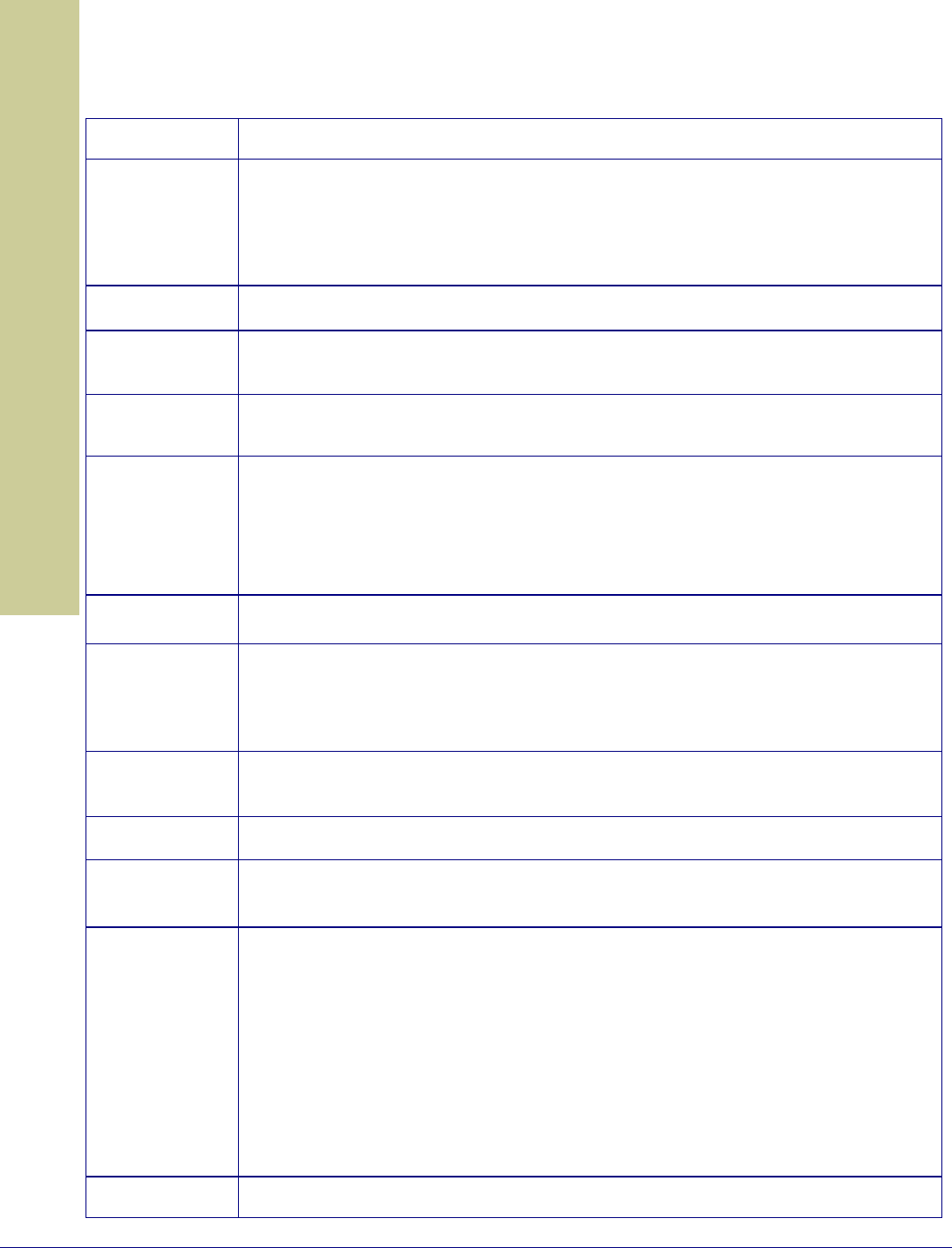

Figure 15. A properly suspended cable device loop with 9 gauge wire.

Figure 16. A cable device loop support wire made with 9 gauge wire. This set is for a

lethal cable device because of the woody rooted vegetation that provides for

entanglement.

trail. Avoid setting on uphill and downhill parts of a trail—

regardless of which way the coyote is traveling, its head will

not be in a good position to enter the cable device’s loop.

For trails that traverse side hills, anchor the cable device

on the downhill side of the trail. A captured coyote will

naturally work against the anchor downhill and provide

little disturbance to the original set location. This becomes

useful when another set may be needed.

Cable devices must be solidly anchored to an immovable

object. This is imperative for a breakaway component to

function properly, thus allowing the release of large, non-

target animals. A breakaway component is any mechanism

incorporated into a cable device that allows the loop to

disassemble when a specified amount of pressure is

applied. Do not use drags to anchor cable devices as there

is no assurance that the drag will catch on an immovable

object. Fence crossings make excellent set locations for

cable devices, but fencing wire should not be used as an

anchor as it moves when pulled.

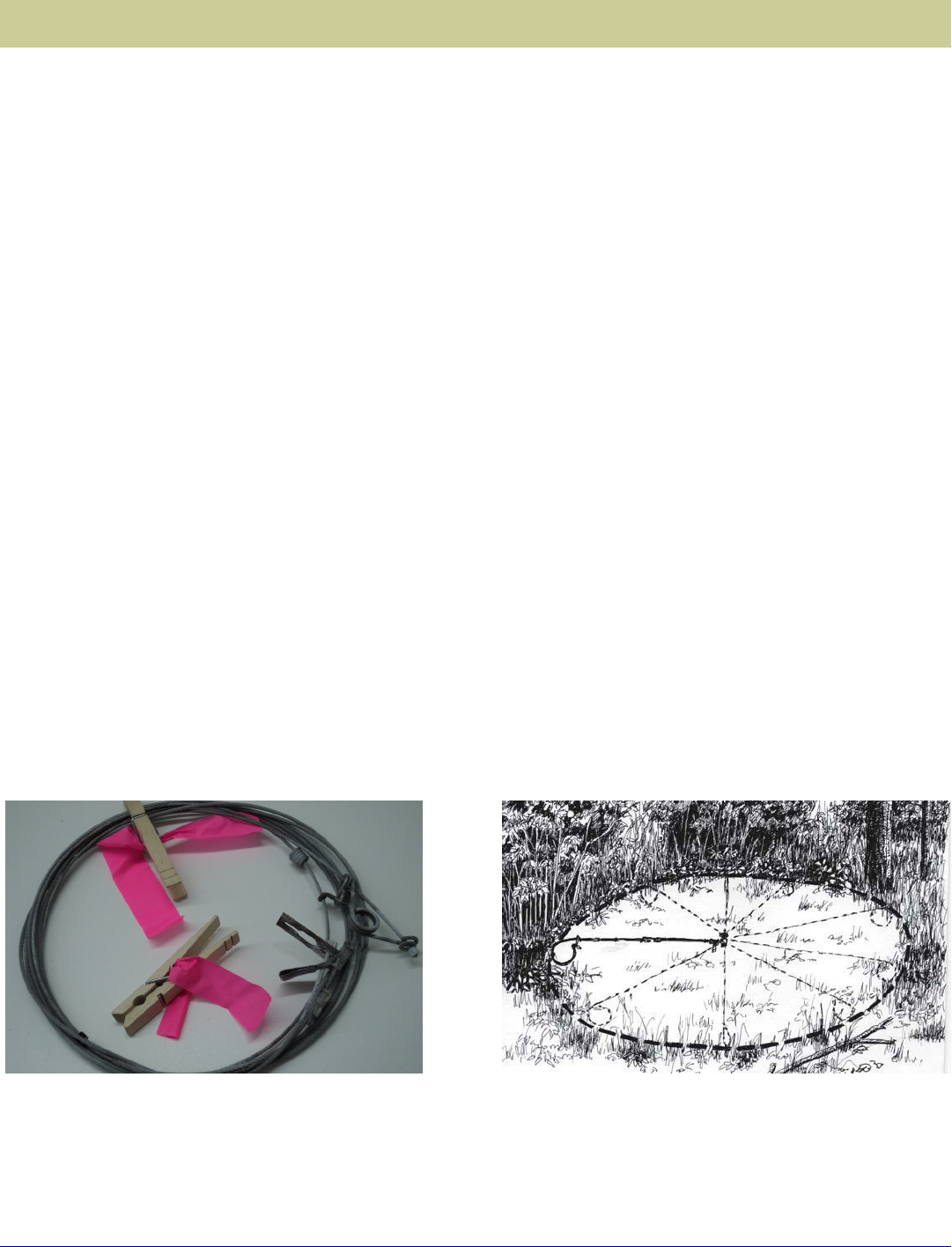

Flag or record each set location with colored survey ribbon

as cable devices easily blend in with the natural

surroundings (Figure 17). Wind can move vegetation

around, and snow can change the appearance of the

landscape. If flagging is secured to vegetation, make sure it

is removed when the set is removed. Place flagging adjacent

to the set, not directly above it. In some areas, flagging can

attract people who may disable or take the devices.

Restraining Cable Device: Restraining cable devices are

excellent tools for live-capturing coyotes. This restraint

system is a good choice for use in urban and suburban

environments, or any location where domestic dogs may be

captured. Live restraints have been used effectively for

resolving wildlife conflicts and capturing animals for

research.

Restraining cable devices incorporate a relaxing lock. The

relaxing lock allows the cable’s loop to tighten with tension,

but it does not keep its place on the cable and will move

slightly backward when tension stops. Relaxing locks are

made so that when assembled, the cable passes through

the lock to make the cable loop smaller or larger. The pass-

through holes are slightly larger, allowing the lock to slide

freely on the cable. Even though the lock can move slightly

in either direction on the cable, an animal cannot shed the

loop from its neck.

When setting a restraining cable device, choose set

locations that are free of objects that could cause

entanglement, such as trees, fences, machinery, and any

woody, rooted vegetation larger than ½ inch (1.2 cm) in

diameter.

Page 19 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Figure 17. Colored survey flagging threaded through the center of hinged

clothespins works well for keeping cable devices organized and identifying

set locations. Attach one to each coiled cable device when storing the cable;

remove it and attach it to nearby vegetation or another structure to identify

the set location once the cable device is set; and recover when the cable

device is removed.

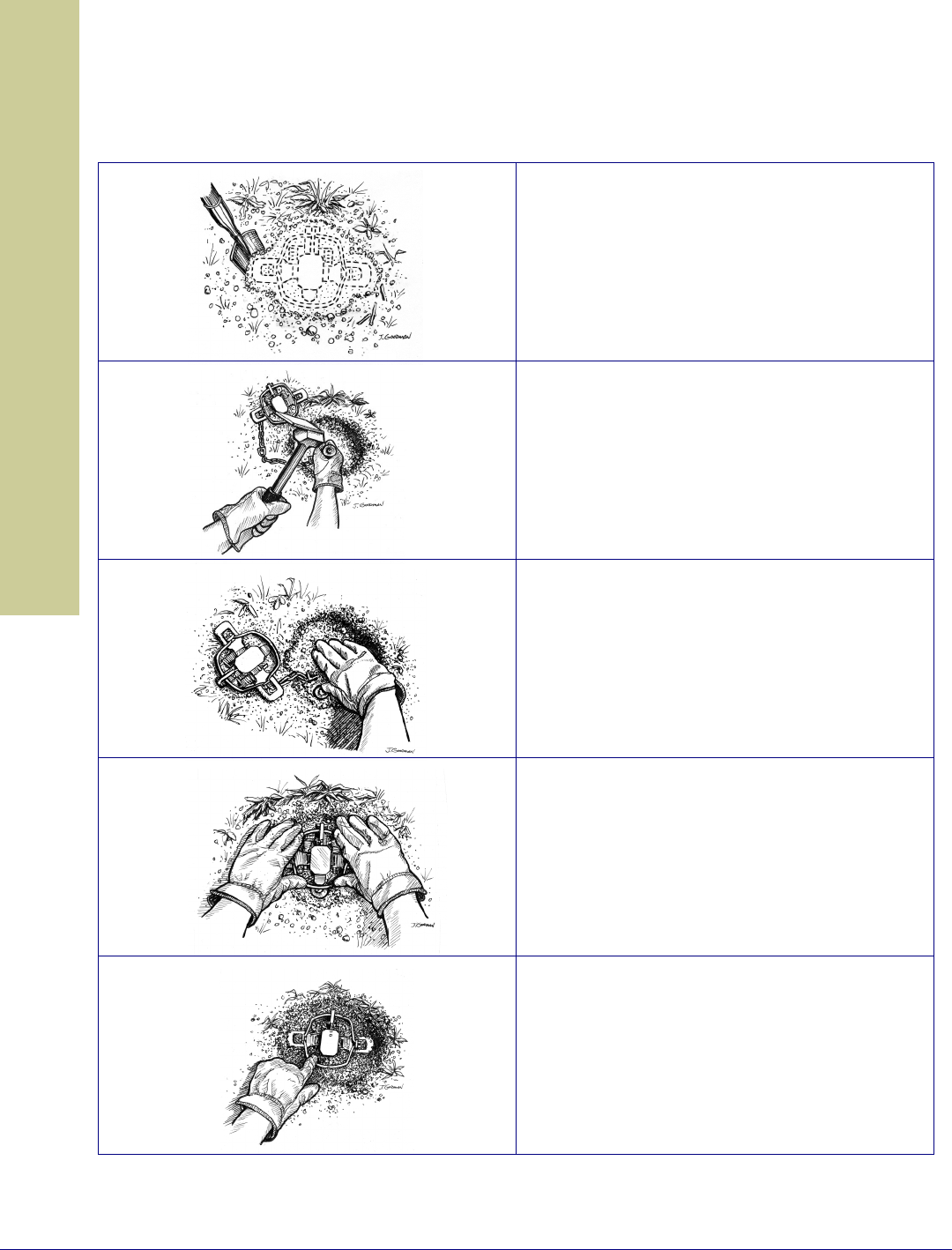

Figure 18. An example of a catch circle with a cable device.

traveling coyotes to visit. Some may come to eat, smell

identifiers (like urine or scat) left by other coyotes or leave

scat or urine of their own.

Once coyote sign is found at a draw station, backtrack to

the coyotes’ entrance and exit trails and choose set

locations as far from the draw station as possible (i.e., 100

to 500 yds (91 to 457 m) are recommended). Consider the

following when making a draw station trap set:

• Making sets too close to the draw station may reduce

their effectiveness. The closer a coyote gets to a draw

station, the more alert it becomes. It is their intent not

to surprise or be surprised by another coyote at the

same location. An alert coyote behaves differently than

a trailing coyote and may result in a poor catch or no

catch.

• Setting traps or cable devices too close to a draw

station increases the potential for catching non-target

animals, such as raptors and scavengers that may visit

the site. It is common for birds to land in the open and

walk 10 to 50 yds (9 to 45 m) to reach a draw station.

Using Dogs

Trained dogs often assist in coyote damage management. A

well-trained dog can help locate appropriate places to set

capture devices by alerting their handlers to areas where

target animals have traveled, urinated, or defecated.

Trained dogs can also aid in the application of other

methods by detecting individuals, dens, or attracting coyotes

into shooting range. Properly trained and disciplined dogs

should not make contact with coyotes and have minimal

effect on non-target animals.

Handling and Euthanasia

Wear protective equipment (i.e., gloves, safety glasses)

when handling live or dead coyotes. Avoid contact with

claws, teeth, blood, saliva, urine, or feces.

Coyotes captured in restraining devices may need to be

transported to a different location for euthanasia. A

Page 20

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Restraining cable devices are approximately 5 ft (1.5 m) in

length and limit an animal’s free reign when captured. If

this “catch circle” (Figure 18) is not free of objects, an

animal will be able to wrap the cable tight against them

and become entangled. When this occurs, the lock cannot

relax, and the animal will asphyxiate. Restraining cable

devices should be checked daily as they are not designed to

hold live coyotes for long periods of time.

Lethal Cable Device: Lethal cable devices include a non-

relaxing lock. This lock allows the loop of the device to

tighten with tension but prevents it from loosening when the

tension stops.

Many modern cable devices incorporate a small

compression or torsion spring that puts pressure on the

lock to bind it more securely against the cable.

Set lethal cable devices in areas with natural objects that

can cause entanglement and restrict movement, like small

trees or brush, or add an entanglement object. An example

of an entanglement object is a -inch (1.2 cm) diameter

or larger 4 ft (1.2 m) long re-rod stake. These are

commonly called “tangle rods” and are used to support the

cable loop and anchor the device. If a captured coyote is

allowed free reign it may apply great stress to the cable

device, causing a component to fail or providing time for

the coyote to chew through the cable.

Draw Stations

Draw stations are locations that may already exist (e.g.,

carcass disposal sites) or are created by adding lure or bait

to increase coyote interest and activity in an area. A draw

station may be something as simple as lure on a piece of

hide hung in a tree, a road-killed animal (legally possessed),

or carcasses from previous trapping efforts. Moving dead

livestock is generally restricted by state law. Landowner

permission is required if wild animal carcasses are brought

onto the property. Check state trapping regulations

regarding the use of draw stations and certain baits.

The longer a draw station is in place, the more coyote

activity it will receive. The draw station is a place for

catchpole and large cage trap will aid in the removal and

transport of an animal from the device.

When working with a restrained coyote, move slowly and

deliberately. Speak in a calm voice. Place a hood or towel

over an anesthetized coyote’s eyes to reduce stress. Keep

a live coyote cool or in a shaded area to avoid heat-related

injury.

The American Veterinary Medical Association provides

guidelines for euthanizing animals with firearms. Captured

coyotes are commonly euthanized with a well-placed shot

to the brain using a hollow-point bullet from a .22 rimfire

cartridge (or of equivalent or greater velocity and muzzle

energy).

Euthanasia drugs, such as a solution of pentobarbital and

phenytoin, can also be administered by trained specialists.

Disposal

Follow local and state regulations regarding carcass

disposal. In some disease-related cases, deep burial or

incineration may be warranted. When removing coyotes

with restricted use pesticides, follow label instructions for

proper carcass disposal. Care must also be taken with the

disposal of carcasses that contain euthanasia drugs. Deep

burial or incineration is required to avoid secondary

hazards to animals that may feed on the carcass.

Economics

Coyotes cause considerable damage to livestock and

natural resources in the United States. For example, even

with coyote damage management programs in place,

livestock producers lose in excess of $115 million in

livestock annually to coyotes.

The value of livestock killed, or the reduced value of

injured livestock represents a small fraction of the

actual costs of predation. Other damage costs include

looking for injured or dead livestock, disposing of dead

livestock, caring for livestock injured or exhausted as a

result of being pursued or attacked, and obtaining

replacement animals.

Coyote damage management implementation costs are

additive to the direct damage costs. From 2000 to

2015, the percentage of U.S. cattle operations using

nonlethal methods to control predators increased from

approximately 3 to 19 percent. For an overview of

coyote predation impacts and use of nonlethal damage

management tools by livestock type, see Table 2.

Coyote predation or damage in urban and suburban

settings is also expensive and includes costs associated

with implementing management methods for aggressive

or nuisance coyotes, protecting and/or replacing exotic

or heritage livestock, and addressing disease related

concerns.

Page 21 U.S. Department of Agriculture

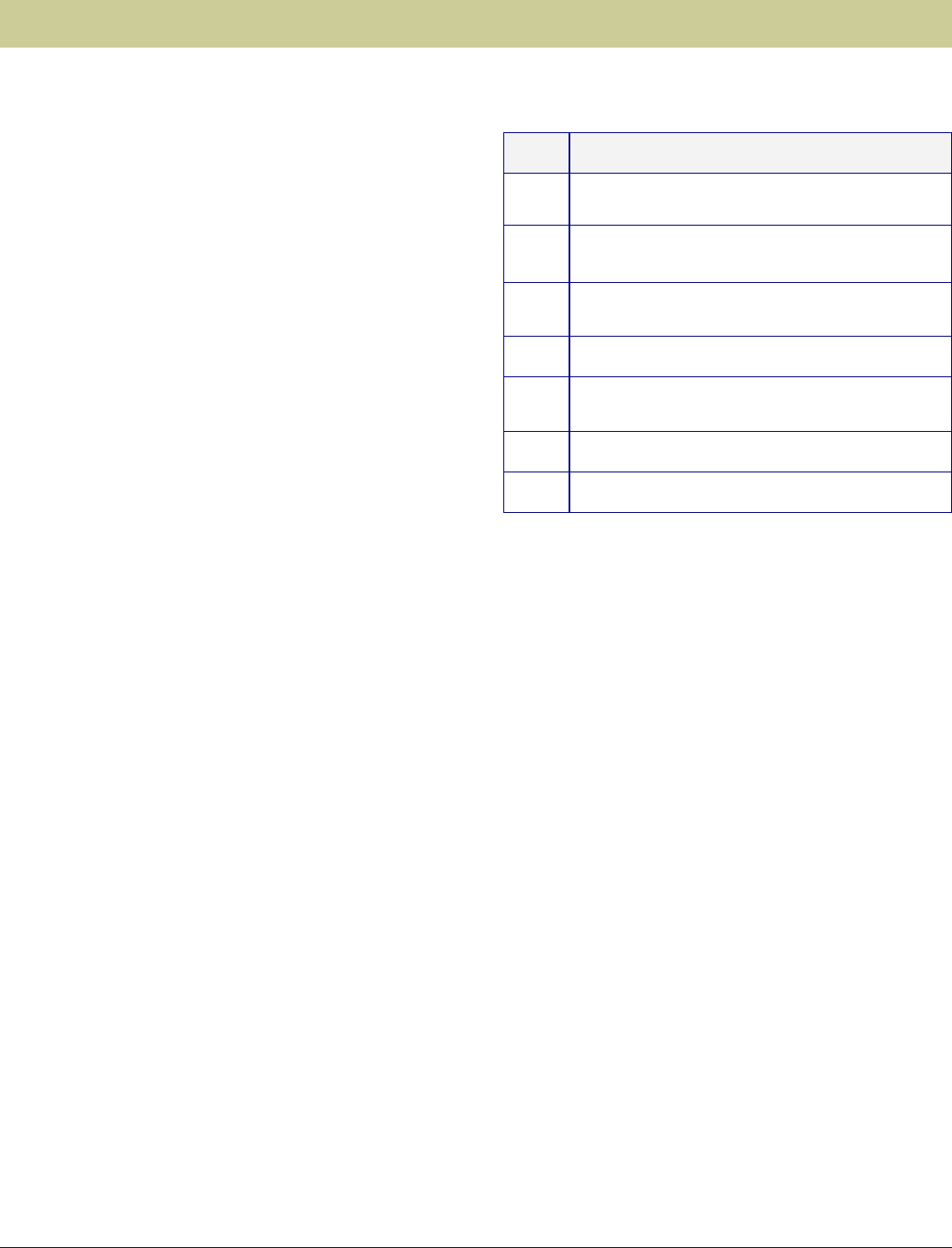

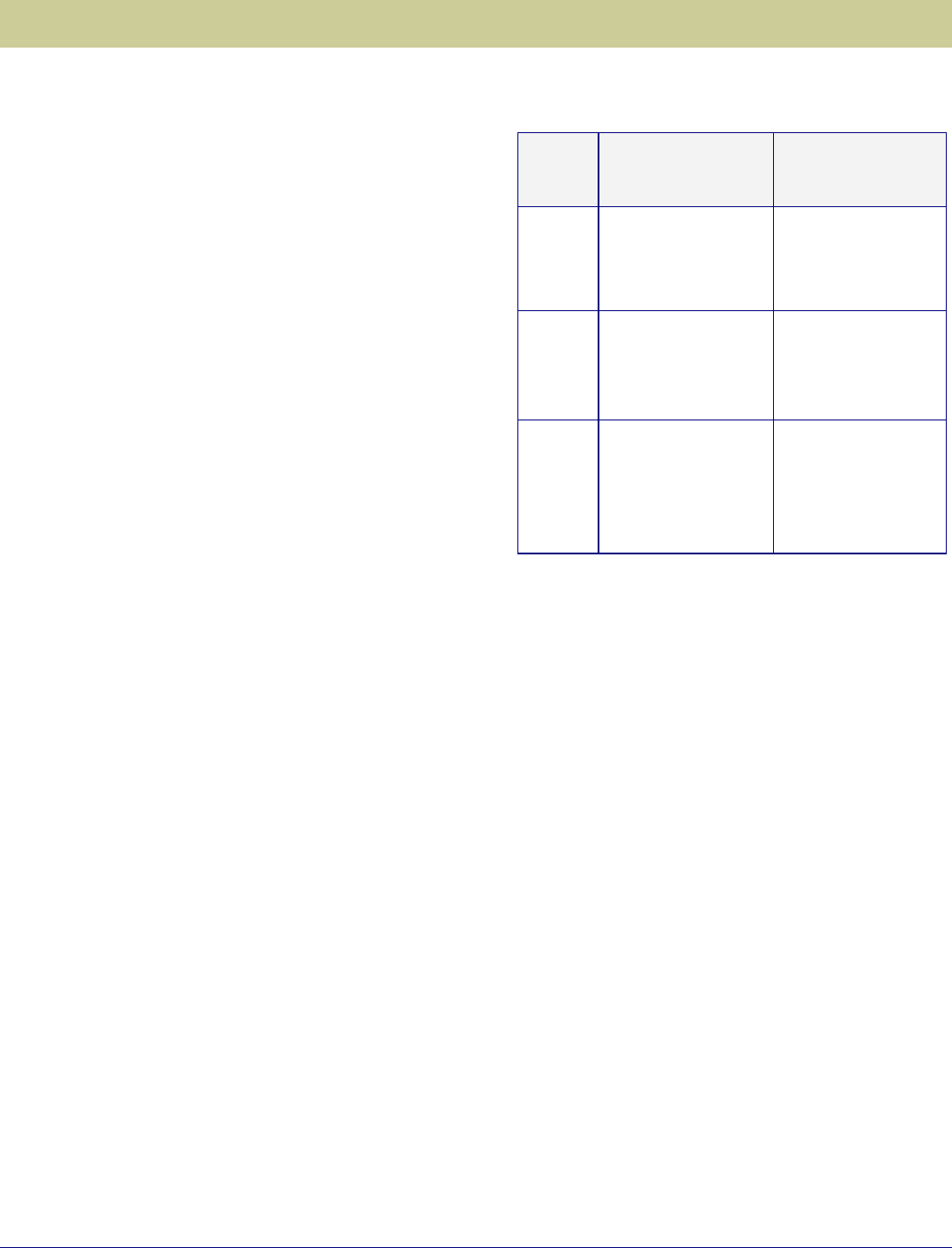

Livestock

Type

Percentage of predator-

related losses due to

coyotes

Use of Nonlethal

Damage Management

Tools

Cattle 40.5% cattle

53.1% calves

Producers spent an

average of $3,000 and

$300 on nonlethal and

lethal tools, respectively

Goats 65% goats and kids

(represents losses from

coyotes and dogs)

Producers spent an

average of $1,085 and

$444 on nonlethal and

lethal tools, respectively

Sheep 54.3% sheep

63.7% lambs

58% of producers used

1 or more nonlethal

tools, such as fencing,

guard dogs, lambing

sheds, and night

penning

Table 2. Coyote predation impacts and the use of nonlethal damage

management tools by livestock type from USDA National Animal Health

Monitoring System reports (2014 goat data, 2015 cattle and sheep data).

Coyote predation can be costly when it impacts recovery

efforts of highly valued endangered and threatened birds,

mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. Threatened

or endangered species protection programs should

consider coyote predation when these species share the

same habitats, and budget for the necessary costs of

prevention or removal.

Species Overview

Identification

Coyotes belong to the Order Carnivora in the Family

Canidae, along with domestic dogs, wolves, foxes, and

jackals (Figure 19).

Physical Description

Coyotes vary in size. Those from eastern regions of North

America are larger and heavier (30 to 38 lbs /13.6–17.2

kg), than those from the west (20 to 35 lbs /9–15.8 kg).

The genealogy of the eastern coyote includes a

hybridization with wolves and dogs resulting in the slightly

larger size. Adult male coyotes are generally larger than

adult females. Pelt colorations range from near white to

black. Some color phases include red and orange.

Coyotes have excellent hearing, sense of smell, and eyesight.

They have pointed ear tips and a pointed nose. The

distance from the top of a coyote’s back to the bottom of

its chest is equal distance from the bottom of its chest to

the ground. Coyotes differ from wolves in that wolves have

rounded ear tips and a square nose, and have

proportionally much longer legs compared to a coyote.

Coyotes have been measured running at speeds of up to 40

miles per hour (64 kilometers (km) per hour) and can sustain

slower speeds for several miles.

Range

Coyotes occur across most of North America from the edge

of the northern tundra to Central America. In the United

States, all 48 contiguous states and Alaska have coyote

populations, though densities vary with habitat quality.

Tracks

Coyote tracks contain four toes with claws and a heel pad.

The track impression is longer than it is wide. Both front

and rear feet have the same shape, but the rear track may

appear slightly smaller than the front (Figure 20). Coyotes

Page 22

WDM Technical Series─Coyotes

Figure 19. Coyotes are members of the canid family. Figure 20. Coyote tracks. Note the front track

(top)

is larger than the rear

(bottom).

Image not to scale.

carry their weight forward, resulting in a larger front

track.

Front foot tracks average 2 inches (5 cm) wide by 2.5

inches (6.3 cm) in length. The rear foot track averages

1.5 inches (3.8 cm) wide by 2 inches (5 cm) in length.

Track impressions vary with animal weight and soil or

substrate conditions. It is best to obtain several

observations and measurements over a greater area to

make an accurate identification.

Tracks made by the front feet show the third toenail

(counting from the inside to the outside of the foot)

slightly longer than the others. The heel pad contains

three lobes. The heel pads on the rear feet tend to have

convex center lobes which cause the lobes on either

side to disappear in the track. This knowledge may be

useful in determining a front or rear foot impression.

Tracks in a single file represent a walking gait; tracks in

a two-step (one track partially over another) represent a

side trot; and a track pattern resembling a “T” (where

the back feet surpass the front feet) represent a gallop.

The walking and side trot gaits may measure 17 to 25

inches (43 to 63 cm) between the same foot-track in

that pattern. When observed, the distance between the

left and right tracks (straddle) is approximately 5 inches

(12.7 cm). The track of eastern coyotes may be slightly

larger and the distance between track impressions of a

traveling coyote slightly longer.

Sign

Coyotes will urinate on elevated clumps of grass, dirt,

old carcass parts, small waste grain piles, or other

similar material as a method of communication. These

locations are obvious when snow is present, less when

surface conditions are dry or hard. Look for evidence of

scratch-ups (i.e., surface scratching or kick-ups done by

the rear feet) adjacent or close to where the urine was

deposited. Similarly, scat (feces) may also be found on

gravel roads or trails and at trail junctions. Visiting

coyotes may also leave their urine and scat on top of or

adjacent to previous deposits.

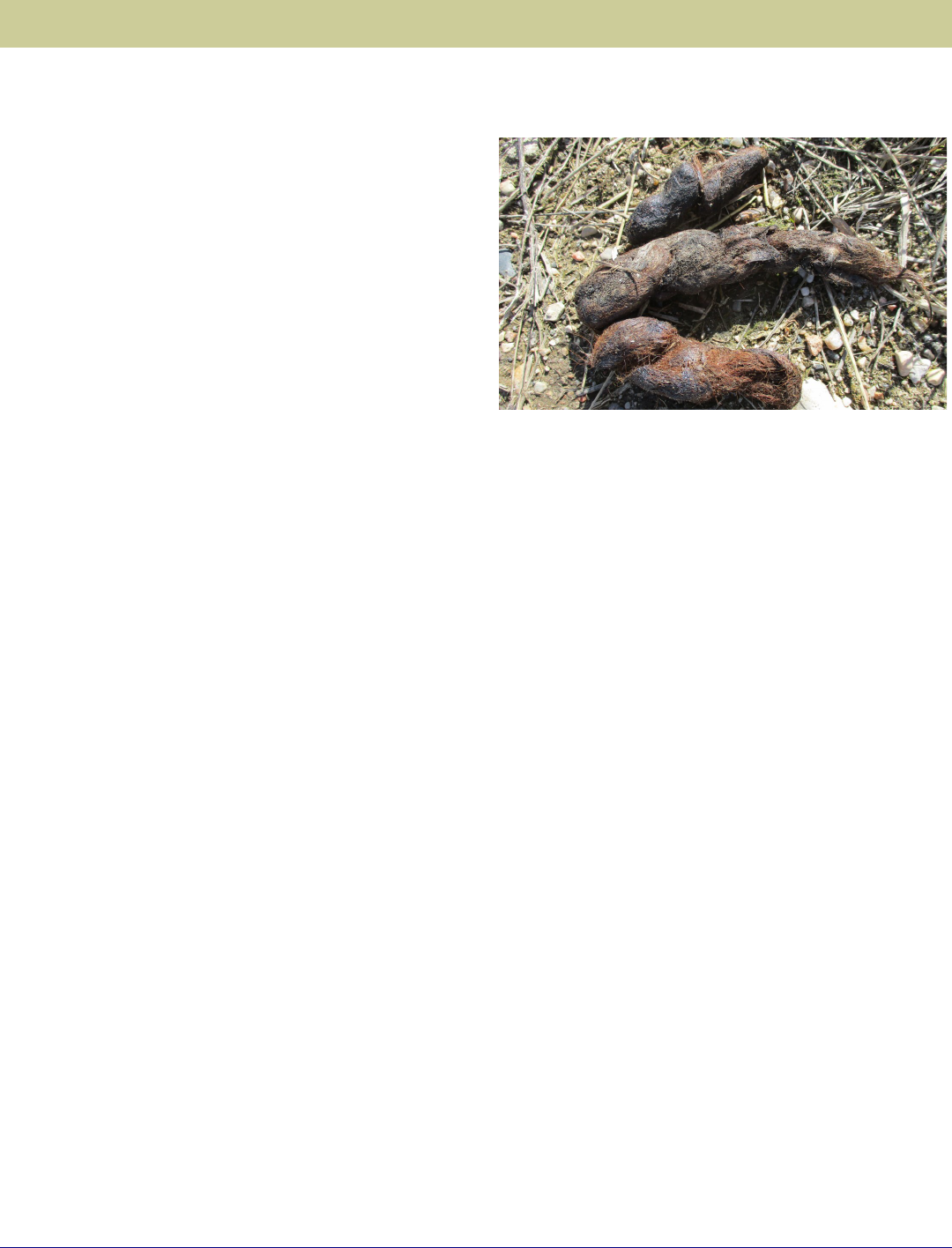

Scat segments (i.e., cords) vary in shape and size

depending on diet and the size of the coyote (Figure 21).

Segments are slightly tapered at the ends and may

measure 2 to 5 inches (5 to 12.7 cm) in length. The cords

may be folded and the last segment to be deposited will be

pointed. Examine fresh segments to determine the diet.

Items that may pass through the coyote’s digestive system

include hair, bone fragments, exoskeletal segments of

insects, fruit pits or seeds, blades of grass, artificial

materials (plastic) or other items. Scat containing

unidentifiable dense black material and a disagreeable

odor is heavy in animal protein, indicating a recent diet of

meat.

Voice and Sounds

Coyotes communicate through a variety of vocalizations. In

a relaxed and safe environment, coyotes will whine and

growl in several low tones which have very different

meanings. Some may serve to gain attention while others

serve to create avoidance. Barking generally serves to gain

attention or announce danger. Howling communicates

location, which sometimes draws others to howl from their

location. Howling can communicate a single coyote

searching for others or may define an occupied home

range. Howling sessions may include a series of barks,

yips, whines, and howls. When this occurs, the listener may

Page 23 U.S. Department of Agriculture

Figure 21. Coyote scat. Note red hair from feeding on a red Angus calf.

be led to believe there are many more coyotes than are

actually present. Two coyotes can easily sound like six. Pup

distress whines and yelps are a typical vocalization for sub-

dominant coyotes when being chased, injured, harassed,

or attacked by others.

Reproduction

Coyotes usually breed in February and March, with gestation

being 60 to 63 days. Females sometimes breed during the

winter following their birth, particularly if food is plentiful.

Females may have been bred by more than one male.

Average litter size is 5 to 7 young. More than one litter may

be found in a single den; at times these may be from females

mated to a single male. Coyotes are capable of hybridizing

with dogs and wolves, but breeding opportunities are rare and

individual species’ behaviors make it difficult.

Adult male and female coyotes provide food to their young for

several weeks. Other adults associated with the denning pair

may also provide food and care to the young.

Juveniles begin emerging from their den by three weeks of

age, and within two months they follow adults to large prey or

carrion. Juveniles are usually weaned by six weeks of age

and will be moved to larger quarters with less structure than

a den hole. The family group usually remains together until

late summer or fall, when juveniles may disperse. Juveniles