Walden University

ScholarWorks

"$ ((')) %$($%)%'")* (

"$ ((')) %$($%)%'")* (

%"") %$

Employee Turnover Intention in the U.S. Fast Food

Industry

Imelda A. Bebe

Walden University

%""%,) ($ ) %$",%'!() 0&((%"',%'!(,"$** ((')) %$(

')%) *( $((# $ ()') %$$#$)$&') %$(%##%$( $)'&'$*' "

$#""*( $((&') %$(%##%$($) $#$) $($*$) )) +)%(

%##%$(

/ ( ((')) %$ ('%*))%-%*%''$%&$((-)"$ ((')) %$($%)%'")* (%"") %$)%"'%'!()($

&)%' $"*( %$ $"$ ((')) %$($%)%'")* (-$*)%' .# $ ()')%'%%"'%'!(%'#%' $%'#) %$&"(

%$)) %"'%'!(,"$**

Walden University

College of Management and Technology

This is to certify that the doctoral study by

Imelda Bebe

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Charles Needham, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration

Faculty

Dr. Kenneth Gossett, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Matthew Gonzalez, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Chief Academic Officer

Eric Riedel, Ph.D.

Walden University

2016

Abstract

Employee Turnover Intention in the U.S. Fast Food Industry

by

Imelda A. Bebe

MS, Kaplan University, 2011

BSBA, Philippine School of Business Administration, 1995

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

January 2016

Abstract

Employee turnover in the U.S. fast food industry has been high, averaging rate 150% per

annum. The purpose of the correlational design study was to examine the relationships

between job satisfaction factors, job dissatisfaction factors, and employee turnover

intentions among fast food employees to determine whether a statistically significant

relationship exists between these variables. The population for the study consisted of 144

fast food restaurant employees working in the East Coast in the United States. The

theoretical framework was Herzberg’s 2-factor motivation-hygiene needs theory, which

describes job satisfaction factors and job dissatisfaction factors. Internet survey data of

144 participants were analyzed using Pearson-product correlation coefficients and

multiple linear regressions analysis. The study findings revealed statistically significant

relationships between job satisfaction factors and employee turnover intentions (p < .01),

and job dissatisfaction factors and employee turnover intentions (p < .01). Among the job

satisfaction factors, responsibility had a stronger relationship with employee turnover

intentions (-.52) compared with other factors. Under job dissatisfaction factors, company

policy had a stronger relationship with employee turnover intentions (-.52) compared

with other factors. In addition, criterion variance of employee turnover intentions

associated with combined job satisfaction factors was stronger (35%) than were the

combined job dissatisfaction factors (31%). The study findings are designed to inform

fast food restaurant managers in taking actions to reduce employee turnover, resulting in

improved business financial sustainability and long-term growth.

Employee Turnover Intention in the U.S. Fast Food Industry

by

Imelda A. Bebe

MS, Kaplan University, 2011

BSBA, Philippine School of Business Administration, 1995

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

January 2016

Dedication

Praise to the Lord for this great opportunity entrusted me. I thank God for his

guidance and help throughout this journey. Once again, God showed me that nothing is

impossible in the world that I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me. This

achievement is greatly dedicated to my beloved father and mother who instilled in me the

importance of education. I always remembered what my father said, “Education is the

greatest treasure that you can have in this world that no one can take away from you;” he

was definitely right!!!

I dedicate this achievement also my husband, Fred Jr., our kids (Christina,

Danika, Fred III, and Nenita), brothers, sisters, relatives, and friends who gave me the

reasons to aim high and kept me going despite of many challenges. Completing this

journey was challenging yet rewarding in the end. This achievement is so remarkable that

I cannot compare. I hope this great achievement will inspire Christina, Danika, Fred III,

and Nenita to obtain their doctoral degrees in the future!

Acknowledgments

Thank God for this wonderful achievement I have accomplished in life and for all

the blessings given to me and to my family. I extend my immense gratitude to my faculty

members, Dr. Charles Needham and Dr. Kenneth Gossett for their endless support, help,

guidance, and understanding throughout this journey. I cannot thank you enough for

helping me in many ways. Without your guidance and assistance, I would have not able

to accomplish this task. To my URR, Dr. Matthew Gonzalez, thank you for your great

support. Dr. Reginald Taylor, thank you for sharing your knowledge that helped me

understand the whole research study process. Thanks to Dr. Jet Mboga and Dr. Trenessa

Williams for your moral and spiritual support; you both inspired me to keep going, be

strong, and persevere throughout this journey.

To all my Kaplan and Walden University former professors, Dr. Carmen Castro,

Dr. Wanda Curlee, Dr. Sherry Giddings, Dr. John Yelvington, Dr. Ray Kalinski, Dr.

Steve Roussas, and Dr. George Spark, thank you for all your advices and prayers. Your

successful achievements in life have also inspired me to finish this challenging journey.

Thanks to all the participants who willingly helped me complete the collection of data. I

thank Walden University staff for their endless support and abundant resources to support

this challenging journey. Thank you, also, to the IRB members for your great feedback to

meet the IRB requirements.

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables .......................................................................................................................v

List of Figures ................................................................................................................... vii

Section 1: Foundation of the Study ......................................................................................1

Background of the Problem ...........................................................................................1

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................3

Purpose Statement ..........................................................................................................3

Nature of the Study ........................................................................................................4

Research Questions ........................................................................................................5

Hypotheses .....................................................................................................................6

Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................8

Operational Definitions ..................................................................................................9

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations ..............................................................10

Assumptions .......................................................................................................... 10

Limitations ............................................................................................................ 11

Delimitations ......................................................................................................... 11

Significance of the Study .............................................................................................12

Contribution to Business Practice ......................................................................... 12

Implications for Social Change ............................................................................. 13

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature ..............................................14

Herzberg’ Motivation-Hygiene Needs (Two-Factor Theory) ............................... 16

Rival Theories of the Theoretical Framework ...................................................... 23

ii

Measurements ....................................................................................................... 29

Job Satisfaction ..................................................................................................... 33

Job Satisfaction Factors ........................................................................................ 37

Job Dissatisfaction Factors ................................................................................... 51

Employee Turnover Intention ............................................................................... 69

Employee Turnover .............................................................................................. 73

Employee Commitment ........................................................................................ 78

Employee Engagement ......................................................................................... 81

Employee Retention .............................................................................................. 82

Transition .....................................................................................................................83

Purpose Statement ........................................................................................................86

Role of the Researcher .................................................................................................86

Participants ...................................................................................................................89

Research Method and Design ......................................................................................91

Research Method .................................................................................................. 91

Research Design.................................................................................................... 93

Population and Sampling .............................................................................................94

Ethical Research...........................................................................................................96

Data Collection Instruments ........................................................................................98

Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) ............................................................................... 98

Turnover Intention Survey .................................................................................... 99

Demographic Survey .......................................................................................... 102

iii

Data Collection Technique ........................................................................................104

Data Analysis .............................................................................................................106

Study Validity ............................................................................................................109

Transition and Summary ............................................................................................112

Section 3: Application to Professional Practice and Implications for Change ................114

Introduction ................................................................................................................114

Presentation of the Findings.......................................................................................115

Job Classification .......................................................................................................128

Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient ............................................. 132

Research Question 1 ........................................................................................... 133

Research Question 2 ........................................................................................... 135

Research Question 3 ........................................................................................... 137

Research Question 4 ........................................................................................... 138

Research Question 5 ........................................................................................... 139

Research Question 6 ........................................................................................... 140

Research Question 7 ........................................................................................... 142

Research Question 9 ........................................................................................... 144

Research Questions 10 ........................................................................................ 145

Multiple Regression ............................................................................................ 146

Applications to Professional Practice ........................................................................151

Implications for Social Change ..................................................................................152

Recommendations for Action ....................................................................................152

iv

Recommendations for Further Research ....................................................................160

Reflections .................................................................................................................161

Summary and Study Conclusions ..............................................................................162

References ........................................................................................................................166

Appendix A: Job Satisfaction Survey ..............................................................................208

Appendix B: Turnover Intention to Leave the Job Scale .................................................213

Appendix E: Permission to use the Turnover Intention Survey ......................................217

Appendix F: Copyright Clearance to Reuse Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene

Theory ..................................................................................................................219

Appendix G: Certification of Completion .......................................................................223

Appendix H: Consent Form .............................................................................................224

Appendix I: Confidentiality Agreement ..........................................................................226

Appendix J: Letter of Cooperation from a Research Partner ...........................................227

Appendix K: Participant Invitation to Participate ............................................................229

Appendix L: Participants’ Reminder ...............................................................................230

v

List of Tables

Table 1. Frequency and Percentage of the Study Sources…………………………….. 16

Table 2. JSS Instrument Reliability Statistics–Cronbach’s Alpha................................. 116

Table 3. ILJ Instrument Reliability Statistics–Cronbach’s Alpha.................................. 117

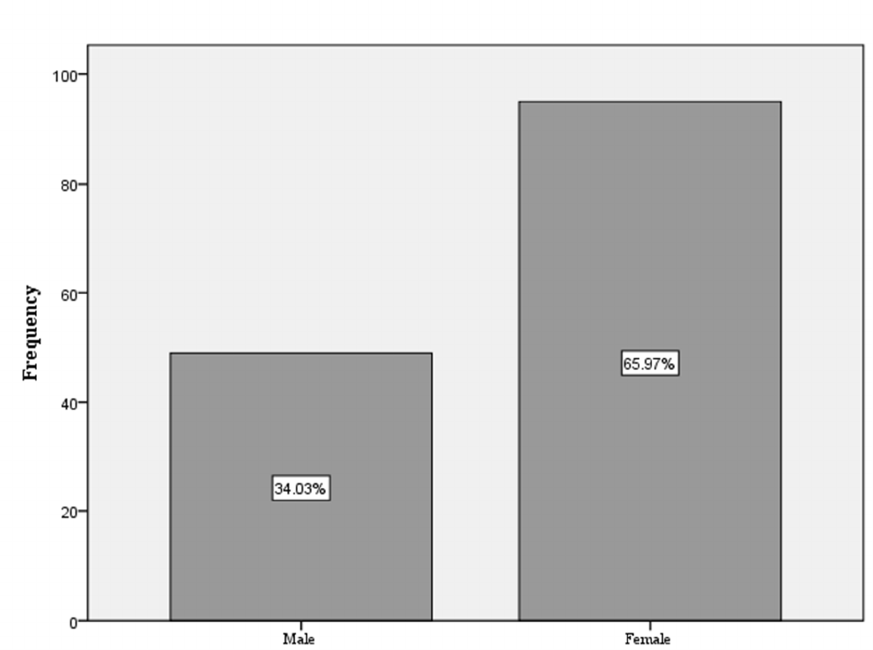

Table 4. Frequency Distribution of Fast Food Participants’ Gender............................. 118

Table 5. Frequency Distribution of Fast Food Participants’ Age .................................. 120

Table 6. Frequency Distribution of Fast Food Participants’ Educational Attainment....122

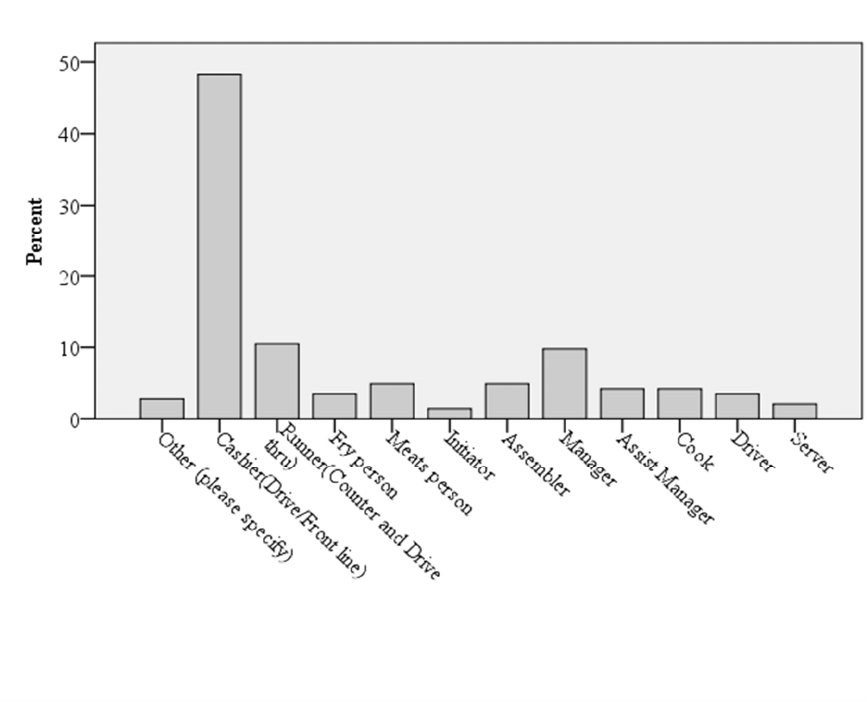

Table 7. Frequency Distribution of Fast Food Participants’ Job Position...................... 125

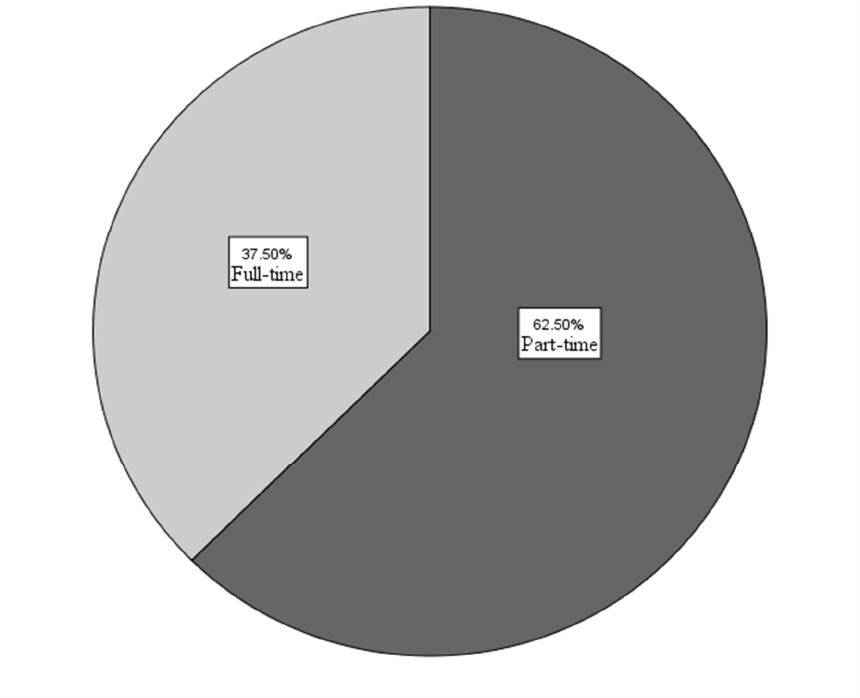

Table 8. Frequency Distribution of Fast Food Participants’ Job Classification..............127

Table 9. Frequency Distribution of Fast Food Participants’ Years of Service............... 129

Table 10. Descriptive Statistics for Age and Years of Working Variables.................... 131

Table 11. Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient Between Job Satisfaction

Factors and Employee Turnover Intentions........................................................133

Table 12. Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient Between Job Dissatisfaction

Factors and Employee Turnover Intentions....................................................... 140

Table 13. Multiple Regressions With Linear Combination of Job Satisfaction Factors and

Employee Turnover Intentions........................................................................... 147

Table 14. Multiple Regressions With Individual Factor of Job Satisfaction Factor and

Employee Turnover Intentions ...........................................................................148

Table 15. Multiple Regressions With Linear Combination of Job Dissatisfaction Factors

and Employee Turnover Intentions......................................................................149

vi

Table 16. Multiple Regressions With Individual Factor of Job Dissatisfaction and

Employee Turnover Intentions............................................................... ............150

vii

List of Figures

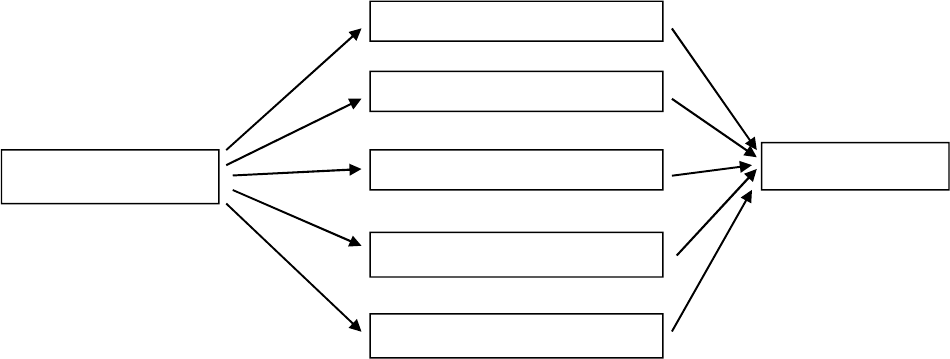

Figure 1. Depiction of Herzberg’ motivation-hygiene needs (two-factor theory) as a

theoretical framework............................................................................................33

Figure 2. Depiction of Herzberg’ motivation-hygiene needs (two-factor theory) as a

theoretical framework ............................................................................................50

Figure 3. Fast Food Participants’ Gender Distribution ....................................................119

Figure 4. Fast Food Participants’ Age Distribution. ........................................................121

Figure 5. Fast Food Participants’ Educational Attainment Distribution. .........................124

Figure 6. Fast Food Participants’ Job Position Distribution ............................................126

Figure 7. Fast Food Participants’ Job Classification Distribution ...................................128

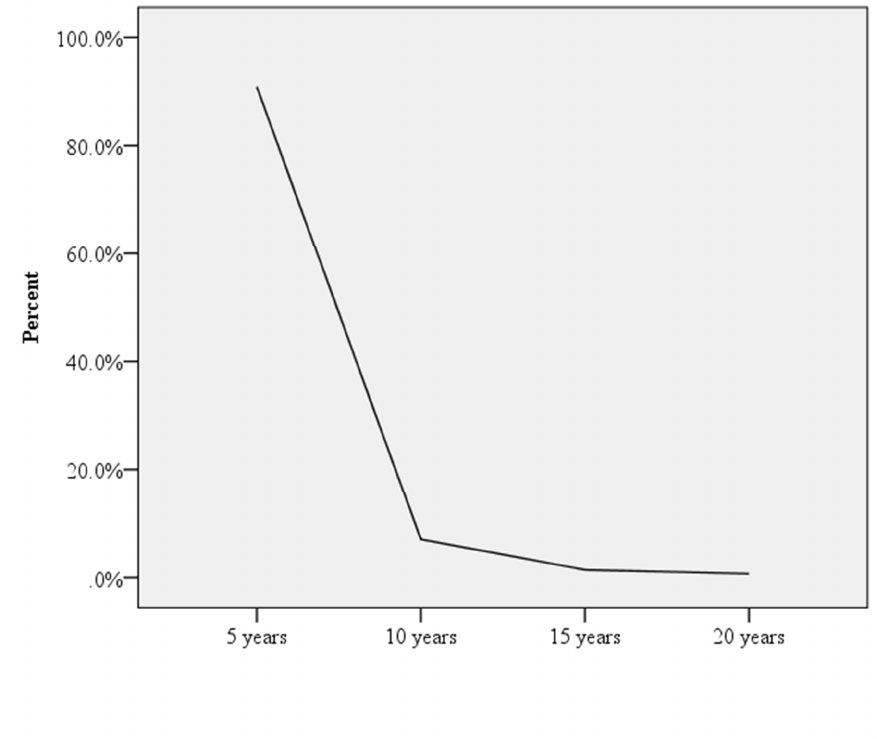

Figure 8. Fast Food Participants’ Years of Service Distribution.................................... 130

1

Section 1: Foundation of the Study

Fast food restaurants make up a major segment of the U.S restaurant industry

(Batt, Lee, & Lakhani, 2014). The U.S. fast food industry comprised 25% of the total

restaurant sales (DiPietro, Gregory, & Jackson, 2013). The four segments of the fast food

industry are (a) quick-service restaurants (QSR), (b) takeaways, (c) mobile and street

vendors, and (d) leisure locations (Kamal & Wilcox, 2014). Quick-service restaurants are

a top segment in the fast food industry in terms of sales performance (Kamal & Wilcox,

2014).

U.S. fast food industry is a vital business sector in the economies because of its

more than 53% market value, contributing to economic growth (Kamal & Wilcox, 2014).

In 2011, the fast food market value in U.S. was approximately $66.2 billion, having

grown by 20% since 2006 (Kamal & Wilcox, 2014). The fast food restaurants throughout

the United States numbered more than 200,000 (Sena, 2014). The growth sales in the fast

food industry increased dramatically, from $6 billion in 1970 to $16 billion in 1975

(Sena, 2014). In 2013, growth sales reached $160 billion, equivalent to about 8.6%

annual rate (Sena, 2014). With effective strategic approaches, the fast food industry

expanded internationally successfully (Sena, 2014).

Background of the Problem

The fast food industry has contributed nationally to U.S. economic growth;

however, increasing employee turnover rates have become the main concern of many fast

food managers (Batt et al., 2014; Dike, 2012). The turnover in the fast food industry is

high compared to other industries (Dike, 2012; Perez & Mirabella, 2013; Sterrett, 2011;

2

Wyld, 2014). Employees’ voluntary withdrawal from a workplace occurs because of (a)

low wages and benefits, (b) lack of training, (c) autonomy, (d) job opportunities, (e) lack

of support from management, (f) and from unfavorable working conditions (Batt et al.,

2014; Royle, 2005; Ryan, Ghazali, & Mohsin, 2011).

Employee turnover is both disruptive and costly to employers, involving

increased direct and indirect costs (Batt et al., 2014; French, 2014; Kacmar et al., 2006;

Ryan et al., 2011). The increasing number of voluntary withdrawals has caused many fast

food managers to experience the hardship of replacing the quitters (Dipietro & Strate,

2008). The fast food industry is popular for having low skilled-labor that discourages

highly skilled workers from applying for vacant positions (Batt et al., 2014; Kwon,

2014). Fast food restaurants primarily hire students with less experience or no experience

that implies highly skilled workers are over qualified.

Employee turnover has an effect on employee efficiency that influences business

financial performance in a negative fashion (Kacmar, Andrews, Van Rooy, Steilberg, &

Cerrone, 2006). The lack of organizational support, work socialization, and employee

involvement creates isolation among employees, which results in lower productivity and

effectiveness (DiPietro & Pizam, 2008; Mathe & Slevitch, 2013). Employee turnover is

caused by lack of employee training, which affects employee competence (Perez &

Mirabella, 2013). Employee incompetence affects the quality service of the fast food

restaurants and thus diminishes the frequency of positive customer experiences

(Harrington, Ottenbacher, Staggs, & Powell, 2012).

3

Problem Statement

The employee turnover rate in the U.S. fast food industry is high at approximately

150% per annum (Dike, 2012; Perez & Mirabella, 2013). Turnover is as high as 300%

per annum for the lowest-level hourly paid employees in some fast food stores (Royle,

2010; Ryan et al., 2011). The general business problem is business operations become

costly and disruptive for many organizational managers because of high turnover

(Dipietro & Strate, 2008; Kacmar et al., 2006). The specific business problem is that

some managers in the fast food industry did not understand the relationship between

employee job satisfaction, employee job dissatisfaction, and employee turnover

intentions.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this quantitative correlational study was to examine the

relationship between employee job satisfaction, employee job dissatisfaction, and

employee turnover intentions in the U.S. fast food industry. It specifically analyzed

associations between five job satisfaction independent variables: (a) achievement or

quality performance, (b) recognition, (c) responsibility, (d) work-itself, and (e)

advancement and growth (Herzberg et al., 1959). It also tracked five job dissatisfaction

independent variables: (a) company policy, (b) supervision, (c) interpersonal

relationships, (d) working conditions, and (e) salary (Herzberg et al., 1959). The

dependent variable was employee turnover intentions in the U.S. fast food industry.

The targeted population included lower level managers and fast food workers

throughout the East Coast of the United States. This population suited the needs for the

4

study because fast food workers in lower-level management and nonmanagerial positions

in the fast food industry experience high turnover (Perez & Mirabella, 2013; Ryan et al.,

2011). This study promotes positive social change by identifying information to help

managers in the fast food industry reduce employee turnover intentions and target factors

important to employees for which managers have control.

Nature of the Study

A quantitative method suited the needs for this study because of the statistical

nature of the data and the quantitative method’s suitability for evaluating hypotheses with

inferential statistics (Singleton & Straits, 2010). The qualitative method did not meet the

needs of this study because the nature of a qualitative approach is to explore and

understand why and how the targeted participant experienced the phenomenon, which

was not the purpose of the study (Bernard, 2013). Mixed methods did not suit the needs

for this study, because the purpose of the study was to examine the relationships between

predictors (independent) and criterion (dependent) variables. Mixed methods require the

combination of exploration of experience to gain an in-depth understanding regarding the

phenomenon with examination of variables to determine the relationship between the

variables (Cronholm & Hjalmarsson, 2011; Venkatesh, Brown, & Bala, 2013), which was

not the case for this study.

I used a correlational design because only correlations would determine the

existence and the strengths of the relationships with a multiple linear regression analysis

(Green & Salkind, 2011). A qualitative phenomenological design did not suit the needs

for the quantitative study, because the nature of the research did not involve analyzing

5

lived experiences to describe and understand the meaning of the phenomenon (Bernard,

2013). In a phenomenological design, a researcher must explore to understand the

importance of the phenomenon to create a new theory; whereas, in a correlational design,

a researcher must examine the relationship of the variables how all predictor variables, as

a whole, predict the dependent variable (Bernard, 2013; Green & Salkind, 2011). A

sequential mixed-methods design did not apply for the study because it used complex

requirements that include observations, interviews, and statistical procedures to support

the argument, as suggested by Naidu and Patel (2013).

Research Questions

The objective of the quantitative correlation study was to examine the relationship

between (a) factors of employee job satisfaction, (b) factors of employee job

dissatisfaction, and (c) employee turnover intentions in the fast food industry.

Research Question 1: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee achievement and turnover intentions?

Research Question 2: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee recognition and turnover intentions?

Research Question 3: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee work and turnover intentions?

Research Question 4: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee responsibility and turnover intentions?

Research Question 5: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee advancement and growth and turnover intentions?

6

Research Question 6: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee job dissatisfaction involving company policies and turnover intentions?

Research Question 7: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee job dissatisfaction involving supervision and turnover intentions?

Research Question 8: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee job dissatisfaction involving interpersonal relationships and turnover

intentions?

Research Question 9: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee job dissatisfaction involving working conditions and turnover intentions?

Research Question 10: Is there a statistically significant relationship between

employee job dissatisfaction involving salary and turnover intentions?

Hypotheses

In this research study, I tested 10 null and alternative hypotheses to determine

whether a relationship exists and how well the independent variables predict the

dependent variables.

H1

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

achievement and employee turnover intentions.

H1

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee

achievement and employee turnover intentions.

H2

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

recognition and employee turnover intentions.

7

H2

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee recognition

and employee turnover intentions.

H3

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee work and

employee turnover intentions.

H3

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee work and

employee turnover intentions.

H4

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

responsibility and employee turnover intentions.

H4

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee

responsibility and employee turnover intentions.

H5

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

advancement and growth and employee turnover intentions.

H5

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee

advancement and growth and employee turnover intentions.

H6

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee company

policies and employee turnover intentions.

H6

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee company

policies and employee turnover intentions.

H7

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

supervision and employee turnover intentions.

H7

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee

supervision and employee turnover intentions.

8

H8

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

interpersonal relationships and employee turnover intentions.

H8

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee

interpersonal relationships and employee turnover intentions.

H9

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee working

conditions and employee turnover intentions.

H9

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee working

conditions and employee turnover intentions.

H10

o

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee salary

and employee turnover intentions.

H10

a

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee salary and

employee turnover intentions.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for the study was Herzberg’s (Herzberg, 1974;

Herzberg, Mausner, & Snyderman, 1959) motivation-hygiene theory, which is also

known as Herzberg's two-factor theory of job attitude, or satisfier-dissatisfier

(motivators-hygiene) theory. Frederick Herzberg developed this motivation-hygiene

theory in 1950 (Herzberg et al., 1959). Herzberg et al. (1959) used the theory to explain

how the factors of job satisfaction and the factors of job dissatisfaction influence

employee turnover intentions. Herzberg et al. identified the following key constructs for

job satisfaction: (a) achievement or quality performance, (b) recognition, (c)

responsibility, (d) work-itself, and (e) advancement and growth. Herzberg et al. also

9

identified the following key constructs for job dissatisfaction: (a) company policy, (b)

supervision, (c) interpersonal relationships, (d) working conditions, and (e) salary.

Herzberg’s (1959, 1974) motivation-hygiene theory implied that if factors related

to job satisfaction go up, turnover intention should go down. According to this model, if

the factors of job dissatisfaction go up, turnover intention should go up as well (Lumadi,

2014). Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory includes information about the factors that

foster increased motivation and satisfaction to reduce employee turnover intentions

(Derby-Davis, 2014; Ghazi, Shahzada, & Khan, 2013). For this study, I purchased a

license from Herzberg’s (1974) publisher, Rightslink, to reuse an excerpt from the

theory’s motivation-hygiene profiles (Appendix F). This license allowed me to use both

of Herzberg’s works because the concentration of the works mainly focuses on

motivation and hygiene theory.

Operational Definitions

Actual turnover: The self-assessment and outcome evaluation associated with

leaving the current job (Stanley, Vandenberghe, Vandenberge, & Bentein, 2013).

Criterion variable: The effect or outcome variable as employee turnover (Petter,

DeLone, & McLean, 2013).

Employee turnover: Employee withdrawal in the form of voluntary and

involuntary withdrawal (Mobley, Griffeth, Hand, & Meglino, 1979).

Informed consent: A process that protects participants from any harm, allowing

participants to participate voluntarily (Judkins-Cohn, Kielwasser-Withrow, Owen, &

Ward, 2014).

10

Involuntary withdrawal: When an employee withdraws from work based on the

company’s decision (Mobley et al., 1979; Phillips, 2012).

Negative correlation: A negative correlation means an inverse correlation occurs

between two variables (Green & Salkind, 2011).

Positive correlation: A positive correlation means a direct relationship exists

between two variables (Green & Salkind, 2011).

Predictor variable: The independent or cause variable that predicts another

variable (Petter et al., 2013).

Turnover intention: The process of leaving the current job (Mobley, 1977).

Turnover intention is the last stage before the actual turnover takes place (Mobley, 1977).

Voluntary withdrawal: An employee’s intentional withdrawal from work (Mobley

et al., 1979; Phillips, 2012).

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

Assumptions

Assumptions are parts of the study that researchers believe are true, where no

verification exists regarding the theory, phenomenon, methodology, instrument, analysis,

participants, power, and results of the study (Dusick, 2014). The assumption in the study

was that the participants answered the survey questions based on what they experienced

and perceived inside the organization regarding employee job satisfaction independent

variables (achievement, recognition, responsibility, work-itself, and advancement and

growth), job dissatisfaction independent variables (company policy, supervision,

interpersonal relationships, working conditions, and salary), and employee turnover

11

intentions in the fast food industry. A review of the literature substantiated the inclusion

of these variables as they related to turnover intentions.

Each participant responded with honesty and accuracy. Participants’ availability

and voluntary participations executed without problems in conducting this research.

Participants who responded to the survey invitation were the representatives of the target

population.

Limitations

The limitations are factors that beyond control of the researchers including (a) the

time constraints, (b) sample size, (c) process of analysis, (d) reporting, and (e) the

instrument used in the study (Dusick, 2014). The process of inquiry design was a cross-

sectional approach, as opposed to a longitudinal process. The success of the process

depended on a limited timeframe. Participants’ busy schedules limited their

participations. The responses of the participants depended on the choices set by the

survey questionnaire, which limited participants to express their views.

The study involved measuring the employee turnover intention and not the actual

turnover. Results of the study data did not generalize with other groups of participants.

The correlational quantitative study only included the fast food industry along the eastern

seaboard in the United States with limited sample size of 130 participants based on the

formula by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007).

Delimitations

The delimitations are factors controlled by me such as (a) selection of

participants, (b) definition of population, and (c) targeted setting (Dusick, 2014). The

12

research problem of this quantitative study was the increasing turnover in the fast food

industry. Employee turnover was one of the major problems of many fast food

organizations, because turnover was costly and disruptive for their business operations.

The targeted population in the study was the fast food workers located in the east

coast seaboard in the United States. The sample of the population was the low-level

employees or non-managerial employees who worked in the fast food restaurants. The

Herzberg’s (1959, 1974) motivation-hygiene theory was the basis theoretical framework

used in the study. The Herzberg’s (1959, 1974) motivation-hygiene theory helped

understand the factors that fostered job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction for many

employees to avoid increasing turnover in the fast food industry.

Significance of the Study

Contribution to Business Practice

The study is important for managers to understand the factors that promote

employee job satisfaction and employee job dissatisfaction that influence employee

turnover intentions to actual turnover. The financial costs involved in employee turnover

in the restaurant industry including fast food restaurants are expensive and costly because

of recruitment problems (Batt et al., 2014; French, 2014; Murphy et al., 2009; Perez &

Mirabella, 2013). Understanding and addressing the factors that led to employee turnover

intentions in the fast food industry might help managers reduce increasing turnover.

The study results may also contribute to effective business practices. By

examining and determining the factors that promote employee job satisfaction and job

dissatisfaction, managers can assess the aspects of job and focus on factors that need

13

attentions. With proper strategies to implement, managers can avoid turnover intention

from happening. For examples, to increase employee job satisfaction with achievement

and recognition, managers must have a periodic performance evaluation based on the

employee performance with feedback. The strategy may increase employee productivity

and increased productivity can increase business profits (Gkorezis & Petridou, 2012;

Haines III & St-Onge, 2012; Kehoe & Wright, 2013).

Another factor that managers can focus on is pay. Pay is a motivating factor for

many employees that influence performance and intention to leave (Kwon, 2014; Misra,

Jain, & Sood, 2013). If business managers improved the employees’ compensation

structure based on the effective performance and competence, then increased employee

performance could affect business performance as well.

Empowering employees by providing an advanced training, autonomy, and

control can help employees perform the jobs with skills, resulting to increased employee

job satisfaction and customer satisfaction. Satisfied customers can result to repeat

business orders, which increase organizational business profit. Satisfied employees

increase employee retention rate.

Implications for Social Change

In examining and determining relationships and the extent of the relationships of

the variables, employers may help improve the business practices or policies. Some of the

business practices are (a) evaluating the employee compensation periodically, (b)

recognizing the effortless contributions and performances of the employees, (c)

empowering the employees, and (d) providing safe and healthy environment. Improving

14

business practices may also improve the conditions of the employees, and increase

employee and business performance that influence business profitability and long-term

growth.

Other implications for positive social change are to help employees to enhance (a)

organizational commitment, (b) employee engagement, (c) job satisfaction, and (d)

motivation. With increased employee job satisfaction and decreased job dissatisfaction,

managers can minimize the employee turnover intentions. Minimizing the turnover

intention can prevent an increasing employee turnover from occurring.

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature

The literature review examines topics including Herzberg’s (1959, 1974)

motivation-hygiene theory consisted with the primary theoretical framework for the

study. Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs and the Hackman and Oldhams’ (1976) job

characteristics model, including strengths, limitations, and weaknesses of other theories,

and the reasons why Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory was the priority theoretical

framework. Other topics include the psychometrical scales such as Job Satisfaction

Scales (JSS) and Job Descriptive Index (JDI), including their established reliability and

validity properties that were used as a guide for choosing the right scale for this study.

The other parts of the literature review include the variables used for the study

such as job satisfaction independent variables and job dissatisfaction independent

variables, and the dependent variable turnover intentions. The job satisfaction

independent variables were (a) achievement, (b) recognition, (c) responsibility, (d) work-

itself, and (e) advancement and growth (Herzberg, 1974; Herzberg et al., 1959). The job

15

dissatisfaction independent variables were (a) company policy, (b) supervision, (c)

interpersonal relationships, (d) working conditions, and (e) salary (Herzberg, 1974;

Herzberg et al., 1959). Each variable tracked in this study had empirical support from

different fields of research to support the relationship between variables.

Other related topics described in this section are employee turnover, causes of

turnover, and implications of the turnover, employee engagement, commitment, and

employee retention. The investigation involved an intensive review of previous research

and findings related to the variables and the theoretical framework guided in the study.

The purpose of this literature review was to clarify research questions, hypotheses, and

identify gaps in previous research.

Strategy for Searching the Literature

I used the following databases and search engine used to locate peer-reviewed

journal articles, dissertations, books, and U.S government and private websites:

ABI/Inform Complete; Academic Search Complete; Business Source Complete;

Dissertation, and Theses at Walden University; eBook Collection (EBSCOhost); Emerald

Management Journal; Google Scholar; Hospitality & Tourism Complete; and PsycINFO.

The following search terms used employee achievement, employee recognition, employee

communication, employee responsibility, employee growth, employee advancement, pay,

company policy, training, and working conditions. Other terms used for the study were

voluntary withdrawal, involuntary withdrawal, employee turnover, turnover intention,

job satisfaction, job dissatisfaction, employee engagement, and employee commitment.

To further expand the topic of the study, the other words used were restaurant industry,

16

fast food industry, quick-service restaurants, intention to leave, Herzberg’ motivation-

hygiene theory (two-factor theory), Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Hackman and

Oldham’s job characteristics model, job satisfaction scale (JSS), and job descriptive

index (JDI). The literature review included different peer-reviewed journal articles,

dissertations, books, and other sources published within 5 years of my anticipated

graduation. The frequency and percentages of the resources such as books, dissertations,

peer-reviewed articles, and other sources are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Frequency and Percentage of the Study Sources

References

Resources Within 5 years Older than 5 years Total %

Books 4 3 7 3%

Dissertations 1 1 2 1%

Peer-reviewed articles 178 13 191 95%

Other resources 2 0 2 1%

Total 202 100%

Herzberg’ Motivation-Hygiene Needs (Two-Factor Theory)

The theoretical framework for this study was based on Herzberg’s (1959, 1974)

motivation-hygiene theory, which is also known as Herzberg's two-factor theory.

Psychologist Frederick Herzberg developed the motivation-hygiene theory in 1950

(Herzberg et al., 1959). In the early 1960s, Herzberg used the motivation-hygiene theory

17

first in AT&T’s College Recruitment program for employee selection and training

purposes (Herzberg et al., 1959). Herzberg et al. (1959) incorporated the two factors with

job enrichment. The reprinting of the books occurred for more than 200 times

internationally and applied in different fields and various business sectors (Herzberg,

1974; Herzberg et al., 1959).

Herzberg’s (1959) and Herzberg et al.’s (1974) motivation-hygiene theory

describes the factors that promote employees’ job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction. The

key factors for job satisfaction listed in this theory are (a) achievement, (b) recognition,

(c) work-itself, (d) responsibility, and (e) advancement and growth. The key factors for

job dissatisfaction listed in this theory are (a) company policy, (b) supervision, (c)

interpersonal relationships, (d) working conditions, and (e) salary. Herzberg et al.

described the motivation as motivational factors or satisfiers and hygiene as dissatisfiers.

Herzberg et al. (1959) also emphasized that both job satisfaction and job

dissatisfaction are two different phenomena. According to this theory, the absence of

hygiene factors does not create employee job satisfaction or motivation; instead, an

employee can consistently feel the job dissatisfaction even when hygiene factors were

present (Herzberg, 1974). The increasing complaints of many employees because of

hygiene factors accelerates hygiene crisis for many business managers (Herzberg, 1974).

Herzberg (1974) added that motivation and hygiene factors had different job employee-

performance outcomes. Motivators are factors that provide long-term results to the

employees’ performance as opposed to hygiene factors or dissatisfiers that produce short-

term effects towards employees’ performance and job attitudes.

18

Herzberg (1974) also noted that the source of employee job satisfaction was

because of job content, whereas job dissatisfaction was because of work context. Job

content is related to jobs that make employees happy through recognition, achievement,

and career growth (Herzberg, 1974). Job context has an indirect relationship with the

employees’ job performance, but relates to factors under the control of companies such as

salary, working condition, and security (Herzberg, 1974).

Herzberg et al. (1959) further explained the factors of job satisfaction,

emphasizing that employee achievement or a quality performance was a leading factor to

employee job satisfaction. In short, employees can achieve higher job satisfaction if they

achieve their goals or if employees performed well with quality. High-quality

performance is associated with employee satisfaction and produces positive behavior

towards employees’ jobs (Herzberg et al., 1959). In addition, employee recognition

increases employee satisfaction where feedback based on the employee’s performance

plays a vital role (Herzberg et al., 1959).

Having a good relationship with customers provides motivation and job

satisfaction to the employees (Herzberg et al., 1959). Responsibility involves self-

scheduling, authority to communicate, control of resources, and accountability (Herzberg

et al., 1959). Self-scheduling consists of how employees make a schedule for customers

to meet their high expectations. Having authority to communicate with the customer(s)

and others to avoid delays in completing the job makes employees satisfied with their

job. Employee job satisfaction increases when employees have rights and when tools are

19

available to complete the assigned tasks with complete responsibility (Herzberg et al.,

1959).

Advancement and growth is one of the job satisfaction factors. Advancement and

growth refer to learning new things to enhance (on the job training) employee’s

competence (Herzberg et al., 1959). Advancement and growth can achieve by training.

Employees with proper and sufficient training are competent to do the assigned job.

Herzberg et al. asserted with proper and effective training, employees can grow and

advance their career. Salary and relationship with employees are hygiene factors or job

dissatisfaction factors (Herzberg et al., 1959). Copyright clearance location exists in

Appendix F. Issued license applies to both Herzberg’s works because the concentration

of works primarily focuses on motivation-hygiene theory.

Research findings of using motivation-hygiene theory. Many researchers in

different fields later extended the motivation-hygiene theory. Lumadi (2014) used the

theory of Herzberg’s (1959) motivation-hygiene theory for the exploration of factors that

promote dissatisfaction for many teachers to implement the new school curriculum.

Lumadi (2014) found some factors that influence employee job dissatisfaction such as job

security, training, job responsibility, and curriculum transformation process. Lumadi

(2014) added that empowering employees can promote new effective school curriculum.

Research findings include the suggestion that employees must have an active

participation in school transformation process including in decision-making (Lumadi,

2014).

20

Derby-Davis (2014) also used the same theory for the purpose of job satisfaction

and intention to stay on the job. Derby-Davis found that motivation and hygiene factors

are significant factors to meet job satisfaction to decrease turnover intent in a nursing

industry. Ghazi et al. (2013) utilized the Herzberg’s (1959) motivation-hygiene theory to

quantify the level of satisfaction and motivation of employees towards the job. The study

findings revealed that the motivation of employees relied on the fulfillment of hygiene

factors. As suggested, hygiene factors must remain a priority to achieve a higher level of

motivation and satisfaction to increase employee performance (Ghazi et al., 2013).

Islam and Ali (2013) used the model of Herzberg’s (1959) motivation–hygiene

theory to determine the work factors that promote job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction

to the teachers in the university private sector. Islam and Ali (2013) found work factors

that promote employee satisfaction for many teachers such as: (a) achievements, (b)

recognition, (c) work itself, (d) responsibility, and (e) advancement. Among the

motivators, achievement and work itself include better employee satisfaction than other

motivators (Islam & Ali, 2013).

In contrary, Islam and Ali (2013) discovered that employee pay, university policy,

and growth opportunity are dissatisfiers that affect employee job dissatisfaction. Islam

and Ali (2013) also found that supervisions, relationships with the supervisors and co-

workers, and working conditions positively affect employee satisfaction. Relationship

with co-workers provides better satisfaction as opposed to other hygiene factors (Islam &

Ali, 2013).

21

Teck-Hong and Waheed (2011) decided to use the Hezberg’s (1959) motivation-

hygiene theory with convenience sampling. Teck-Hong and Waheed found that working

condition, recognition, policy, and salary increase job satisfaction. Teck-Hong and

Waheed added that working condition has the highest level of employee’s motivation, as

opposed to employee salary. Flores and Subervi (2013) argued that growth and

advancement are the leading motivators to keep satisfied with the job and reasons to stay.

Implications of using motivation-hygiene theory. The implications of applying

motivation-hygiene theory to employee management brought different outcomes for

many researchers. To analyze the results of using Herzberg’s (1959) motivation-hygiene

theory, most of the motivator factors such as achievements, recognition, work itself,

responsibility, and advancement supported the views of Herzberg in motivation-hygiene

theory in terms of job satisfaction (Islam & Ali, 2013). On the other hand, the hygiene

factors such as pay and university policy also supported the view of Herzberg in terms of

job dissatisfaction.

However, other hygiene factors such as supervision, relationships with the

supervisors and co-workers, and working conditions promoted satisfaction for many

teachers instead of promoting job dissatisfaction (Islam & Ali, 2013). The research result

found contradicted to Herzberg’s (1959) view in motivation-hygiene theory added by

Islam and Ali (2013). The researchers found growth opportunity motivational factors as

opposed to the belief of Herzberg in motivation-hygiene theory (Herzberg, 1974;

Herzberg et al., 1959).

22

The study results could not generalize to all private university sectors in Pakistan

except in the district of Peshawar (Islam & Ali, 2013). The sample size used in the study

was small; therefore, future researchers could use bigger sample sizes by considering

more districts (Islam & Ali, 2013). Potential consideration in the future research is a

comparison of job level satisfaction among teachers in private and public sectors (Islam

& Ali, 2013). The results of the study can enhance the quality of teaching performance

among teachers regardless of service sectors to improve the learning experiences of many

students (Islam & Ali, 2013).

Teck-Hong and Waheed (2011) used the motivation-hygiene theory to determine

the factors that motivate and satisfy employees working in retail stores in Malaysia. The

research results demonstrated that hygiene factors overweighed the motivation factors,

meaning the employees had more job satisfaction with the contributions of the working

conditions, company policies, and salaries than other motivators excluding recognition

(Teck-Hong & Waheed, 2011). The employees found recognition as a motivating factor,

which supported the findings of Herzberg (1974). In addition, hygiene factors as a source

of job satisfaction contradicted to the view of Herzberg. The hygiene factors according to

Herzberg (1974) and Herzberg et al. (1959) are sources of job dissatisfaction and not job

satisfaction for many employees.

Teck-Hong and Waheed (2011) suggested that retailing store managers must

focus on working conditions, company policy, recognition, and salary when employing

rewards scheme to increase employee satisfaction, resulting to increased productivity and

performance. Considering employees’ needs and concerns, employees can provide better

23

service performance that can affect business profitability because of customer satisfaction

(Teck-Hong & Waheed, 2011). Moreover, meeting the needs of the employees can

minimize the employee turnover. Reduced turnover can save money, because managers

do not need to spend money for advertising, hiring, and training new employees (Teck-

Hong & Waheed, 2011).

Ghazie et al. (2013) found that teachers from university are both satisfied with

hygiene and motivation factors, but only fulfillment of hygiene factors can motivate

teachers from university. The study results contradicted with Herzberg’s (1974) findings

regarding the hygiene factors that promote job dissatisfaction or no motivation. From the

perspective of Ghazi et al., (2013), researchers recommended considering hygiene factors

as source of employee motivation and satisfaction to increase employee performance.

Rival Theories of the Theoretical Framework

In 1943, Abraham Maslow introduced the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs include five sets of goals such as (a) physiological needs,

(b) safety, (c) social, (d) self-esteem, and (d) growth needs or self-actualization (Maslow,

1943). The hierarchy of needs include a foundation of goals of predominance, meaning

employees cannot achieve the higher needs without meeting the lower needs (Maslow,

1943). Maslow added that each need correlates to one another. Once an individual meets

the lower needs, the higher needs emerge (Maslow, 1943).

Maslow (1943) described the five sets of goals. Physiological needs are the basic

needs of individuals to survive such as water, air, and food. Once individuals met these

physiological needs, safety and security needs are the next target (Maslow, 1943). Safety

24

and security needs occur when individuals feel the threats of the situations such as

economic condition and competition. When individuals feel satisfied with the safety

needs, social (love and belonging) needs occur (Maslow, 1943). Individuals need love

and belongingness as part of the community, groups, or family to communicate,

participate, and share their visions. After achieving love and belonging needs, individuals

want to gain respect from others and feel that others value their contributions to feel the

self-esteem. Self-esteem increases when individuals receive recognition or

acknowledgement in the job performance. Once the individuals satisfied the deficiency

needs, individuals’ growth needs (self-actualization) emerge. Self-actualization occurs

when an individual realizes personal potential and self-fulfillment where growth becomes

the highest need target (Maslow, 1943). Another rival theory of Herzberg’s motivation-

hygiene theory is Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) job characteristic model.

Hackman and Oldham (1976) proposed the Job characteristics model (JCM). The

JCM includes the core job dimensions that influence three psychological states, such as

(a) meaningfulness of work, (b) responsibility of outcomes, and (c) knowledge of results,

resulting in positive and negative outcomes. Positive outcomes increase job satisfaction,

job performance, and employee motivation. Negative outcomes decrease employee

absenteeism and turnover (Hackman & Oldman, 1976). The core job dimensions are skill

variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback (Hackman & Oldham,

1976).

According to Hackman and Oldham (1976), meaningfulness of work can

materialize if skill variety, task identity, and task significance are present. Responsibility

25

of outcomes can occur when employees have autonomy towards aspects of the job

(Hackman & Oldman, 1976). Employees can achieve the results of knowledge through

feedback added by Hackman and Oldman. Meeting the core job dimensions, employees

can increase their motivation, job performance, and work satisfaction, which contribute to

decreased absenteeism and turnover (Hackman & Oldman, 1976). Another tenet of the

theory is that employees have higher personal growth and development, where employees

have ability to do the complex job with higher motivation (Hackman & Oldham, 1976).

Strengths and limitations of rival theories of the theoretical framework.

Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs focuses on the individual needs as a powerful

motivator in the workplace. Deci and Ryan (2014) noted that needs are subdivided into

two categories based on its importance that include lower and higher needs. Higher order-

needs include self-esteem, achievement, and actualization whereas the lower-order needs

include physiological needs (Deci & Ryan, 2014). With research findings, Deci and Ryan

found that higher-order needs are a powerful motivator in the workplace, contributing to

job enrichment. With job enrichment such as feedback, employee performance and

satisfaction can increase (Deci & Ryan, 2014).

Maslow’s (1959) hierarchy of needs include the deficiency and growth needs of

the employees, which may assist employers on what needs motivate and satisfy the

employees the most (Lester, 2013; Matache & Ruscu, 2012). If managers know what

needs, motivate, and satisfy employees the most, then managers can focus primarily on

these needs. Addressing the issues with proper strategies can avoid turnover intentions.

The concept of Maslow’s (1959) hierarchy of needs also consists of individual needs that

26

provide importance and benefits to the employees (Cao et al., 2013). Maslow’s (1959)

hierarchy of needs emphasizes the importance of well-being for not only survival

purposes, but also general purposes to minimize turnover intentions (Jackson et al.,

2014).

Taormina and Gao (2013) concluded that the two needs have the same satisfaction

outcomes. The satisfaction of the lower-order needs is the same as meeting the higher-

order needs (Taormina & Gao, 2013). Under the study findings of Adiele and Abraham

(2013), having low levels of satisfaction in five hierarchies of needs affect the

performance and effectiveness of employees. Enhancing the employees’ working

environment can increase employees’ productivity and commitment. Meeting the

employees’ needs help encourage employees to exceed employer expectations

(Eisenberger, Fasolo, & Davis-LaMastro, 1990).

The job characteristic model can apply to management staff in identifying the job

characteristics that need improvement, what existing potential jobs may help increase

employee work motivation, and what job core dimensions do or do not work as expected

(Hackman & Oldham, 1976). On the view of Kanten (2014), enhancing the core job

dimensions can help employees increase positive job attitudes and quality work

performance. The job characteristics such as feedback and skill variety are effective

factors to use for employees’ job constructing to meet the demands of customers in hotel

(Kanten, 2014). Kanten used the model for four five star hotels in one city, where results

cannot not generalize to other hotels in a different city.

27

The job characteristics model includes individual employees, because each

individual has different response to the situation (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). The job

characteristics model consists of aspects of the job that create incentives for motivational

purposes (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). On the other hand, Kanten (2014) found that job

characteristics such as feedback and skill variety have direct correlations with job

constructing, but not the autonomy and task significance.

Kanten (2014) suggested that employees from a hotel must have varied skills and

talents to cope up with the nature of the working environment. In addition, feedback from

managers and coworkers help increase employees’ confidence in performing the jobs

(Kanten, 2014). Employees from the hotel industry do not perceive high autonomy and

task significance because of the nature of job (Kanten, 2014).

Reasons not to choose rival theories of the theoretical framework. The reason

why I did not choose Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs or Hackman and Oldham’s

(1976) job characteristic model as a theoretical lens in solving my problem because each

theory has a different nature of study. Each theory has different purposes, contrary to my

study to address the research question and hypotheses. The concept of Maslow’s

hierarchy of needs primarily focuses on the needs of the employees according to the level

of importance. The implication of Maslow’s theory is that employees cannot achieve the

higher needs without meeting the lower needs first (Maslow, 1943).

The job characteristics model involves the core job dimensions that influence

psychological states resulting to behavioral outcomes (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). The

presence of a psychological state is important to achieve the personal and work outcomes

28

(Hackman & Oldham, 1976). In both rival theories, researchers discussed the same topics

regarding job satisfaction, motivation, and turnover (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Maslow,

1943). However, the theory constructs for Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs and

Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) job characteristics model are different from Herzberg’s

(1959) motivation-hygiene theory. The intent of study was to examine and determine the

factors that promote employee satisfaction and employee job dissatisfaction for many

employees that influence turnover intentions to reduce the turnover in the fast food

restaurants. Herzberg’s (1959) motivation-hygiene theory includes the constructs used in

this study. Therefore, the theoretical framework used in the study is appropriate.

Weaknesses of the rival theories of the theoretical framework. The concept of

Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs is that employees must meet the needs in order from

lower-to higher needs, which is in contrast with Başlevent, Cem, and Hasan

Kirmanoğlu’s (2013) findings. Başlevent et al. (2013) found that employees have higher

concerns with the needs directly influenced them, but not necessarily in order. Bayoumi

(2012) supported the notion. Bayoumi found that patients need the self-actualization the

most, and the least is the love and belonging needs. The study findings indicated that

patients meet their needs without first meeting the physiological and security needs,

which is a contradiction to Maslow’s theory.

The weakness of the JCM is that not all core job dimensions (skill variety, task

identity, task significance, feedback, and autonomy) must follow in order to achieve

higher job satisfaction, motivation, and quality performance to lower turnover and

absenteeism (Fried & Ferris, 1987). Samples have unique demographic characteristics

29

and different methods used have different results that influence job characteristics and

personal and work behavioral outcomes (Fried & Ferris, 1987). Added by Hauff and

Richter (2015), in JCM, job satisfaction increases based on the specified situation and

intrinsic aspects of the job outweigh the extrinsic aspects of the job.

Measurements

Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS). A study grounded in Herzberg’s motivation-

hygiene theory, which promotes the factors of job satisfaction and the factors of job

dissatisfaction to measure the constructs (Spector, 1985). Spector’s JSS has nine facet

scales with four questions, equivalent to 36 questions. The nine facet scales are (a) pay,

(b) promotion, (c) supervision, (d) fringe benefits, (e) contingent rewards (performance-

based rewards), (f) operating procedures (required rules and procedures), (g) coworkers,

(h) nature of work, and (i) communication (Spector, 1985). Each question has an ordinal

scale with a 6-point-Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

To assess the employees’ attitude towards the job or aspects of the job,

researchers used the JSS in different field of researches, privately or publicly (Spector,

1985, 1997). The internal consistency reliability of JSS instrument is .91 using

Cronbach’s coefficient alpha derived from 2,870-sample size (Spector, 1985, 1997).

Avdija and Roy (2012) used the JSS in different prisons in Atlanta to assess the level of

employees’ job satisfaction. The JSS internal consistency reliability was α =.878 obtained

from 480 participants (Avdija & Roy, 2012). Using multivariate regression analysis,

Avdija and Roy (2012) found that age and working conditions had direct correlations

30

with job satisfaction, where the total variation in the job satisfaction among the prison

employees was 30% (Avdija & Roy, 2012).

Wozencroft and Hardin (2014) indicated that previous researchers tested the

original JSS in 19 different samples to meet reliability and validity norms. Primarily,

researchers used JSS for human services, but since then JSS applies to all organizations.

To conduct a research in Phoenix, Arizona for employees and volunteers in recreation

management, Wozencroft and Hardin suggested utilizing the JSS questionnaire for

assessing the employees’ level of job satisfaction to determine the influence of job

satisfaction for future services. One hundred and thirteen students successfully

completed the questionnaires. Wozencroft and Hardin study findings indicated that job

satisfaction directly related to turnover intention, commitment, and retention with .85

Cronbach coefficient alpha.

Job Descriptive Index (JDI). Smith, Kendall, and Hulin introduced the JDI in

1969; this index was subsequently revised by JDI Research Group in 1985 (Kihm, Smith,

& Irwin, 2014). In 1985 according to DeMeuse, JDI was a popular scale used by many

researchers, professors, and employees in different fields for rating employees’ job

satisfaction to include pay, promotional opportunities, supervision, work itself, and

coworkers (Kihm et al., 2014). The development and refinement of JDI continued for

more than 50 years under the JDI research group, which includes different individuals

with different backgrounds in research, psychology, and behavioral science (“Bowling

Green,” n.d.).

31

The JDI instrument has five facets where employees can rate their job satisfaction

on each area to include (a) coworkers, (b) the work itself, (c) pay, (d) opportunities for

promotion, and (e) supervision (Kihm et al., n.d). The continued revision of JDI helped

increase the internal reliability of an instrument using coefficient alpha (a) opportunities

for promotion .87, (b) people at work .88, (c) present pay .86, (d) supervision .91, and (e)

work on present job .90 (Holt, 2001). Holt indicated that researchers can measure the JDI

through a nominal scale Yes, No, and ?, which is equivalent to 1, 2, and 3 answers. The

JSS questionnaire includes positive and negative short words or phrases. In a positive

response, Y response shows satisfaction (Holt, 2001). In scoring, Y is 3 points, N is 0

point, and ? is 1 point. In a negative response, Y means dissatisfaction. An unfavorable

item is the reversed score, where N has 3 points, Y has 0 point, and ? has a 1 point (Holt,

2001). Each subscale must have an individual score, where some items are reversed

scores.

To collect the data, secondary resources were appropriate such as SSS and census

databases with random and stratification sampling. The participants included current

employed employees between 18 and 70 years of age and located within the United

States. The response rate was approximately 23%, equivalent to 1600 cases involving

data for intention to quit, job satisfaction, trust management, and demographic variables

(Kimh et al., n.d.). Follow up mailings were appropriate along with incentive provisions,

and multiple survey administrations to avoid biased information.

In other instances, Graeff, Leafman, Wallace, and Stewart (2013) successfully

employed the JDI scale in one of the faculties in the United States. The purpose is to

32

assess the job satisfaction level among physician assistants. With 1,241 target

participants, only 239 respondents successfully participated. Graeff et al. found that the

reliability of JDI is greater than .80. Gui, Gu, Barriball, While, and Chen (2014) also

found the JDI reliability greater than .70 when they assessed the working environment of

many nurse teachers in two different countries. The overall responses from China and UK

are 56.8% through cross-section interview process according to Gui et al.

By analyzing the two instruments, JSS and JDI have acceptable internal

consistency reliability. The reliabilities of JSS in three different sample sizes are .91, .87,

and .85 respectively (Avdija & Roy, 2012, Spector, 1985; Wozencroft & Hardin, 2014).

The reliabilities of JDI is .80 (Graeff et al., 2013; Gui et al., 2014; Holt, 2001). The

reliability result of the JSS is higher than JDI. Therefore, JSS instrument would apply

throughout the study process. Matkar (2012) noted that >0.90 is excellent, 0.80 – 0.89 is

good, 0.70 – 0.79 is acceptable, 0.60 – 0.69 is questionable, 0.50 – 0.59 is poor, and

<0.50 is unacceptable. This implies that JSS is a reliable tool to assess participants’

satisfaction towards aspects of job or job as a whole.

In terms of constructs of both instruments, the JSS has nine facet scales that cover

all theoretical constructs related to the study topic, which met the content and construct

validity. The JDI has five facet scales (pay, promotions and promotion opportunities,

coworkers, supervision, and the work itself), which unfortunately did not meet the

theoretical framework constructs for measurement (Kihm et al., n.d). Therefore, JSS

would apply to measure the constructs. Lack of constructs to measure could violate the

required validity that adversely affects the study findings (Barry et al., 2014). The

33

theoretical model for this study is Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (Two-factor

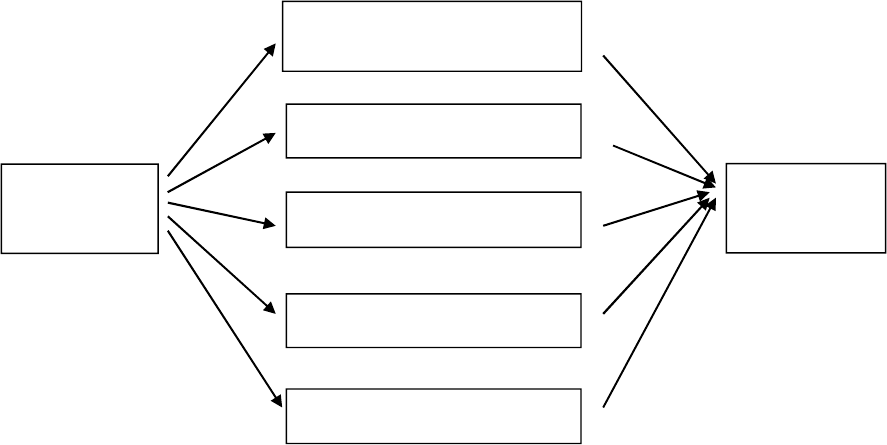

theory) (see Figure 1).

Theoretical Model: Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene Theory

Figure 1. Depiction of Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (two-factor theory) as a

theoretical framework. Adapted from “Motivation-Hygiene Profiles: Pinpointing What

Ails the Organization,” by F. Herzberg, 1974, Organizational Dynamics, 3(2), pp.18-29.

Copyright 1974 by the American Psychological Association and Adapted from The

motivation to work (2nd ed.),” by F. Herzberg, B. Mausner, & B. B. Snyderman, 1959,

New York, NY: John Wiley. Copyright 1959 by John Wiley. Used with permission.

Job Satisfaction

The topic includes an employee job satisfaction in many work settings, private,

public, non-profit organization, and government sections (Herzberg 1974; Herzberg et al.,

1959; Maslow, 1943). The research includes employee job satisfaction using different

conceptual or theoretical frameworks with Herzberg’s (1959) motivation-hygiene theory,

Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs, and the Job characteristics model (Fried & Ferris,

1987; Herzberg 1974). The term job satisfaction has defined in many ways.

Achievement or Quality

Performance

Recognition

Work Itself

Turnover

intentions

Responsibility

Advancement and Growth

Job

Satisfaction

34

Hofaidhllaoui and Chhinzer (2014) described a job satisfaction as a main source

of turnover, describing the level of contentment and attachment of employees toward

their job, specifically or generally. Job satisfaction is the characteristics of the job itself

and the work environment (Cho, Rutherford, & Park, 2013). Locke (1976) defined the

job satisfaction as a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of

an individual job (as cited in Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011; Ünal, 2013). Job satisfaction is

how an employee felt contented with the job (Spector, 1997). Job satisfaction is an

employee’s attitude towards aspects of job or as a whole (Ünal, 2013). Herzberg et al.

(1959) described a job satisfaction as how employee likes or dislikes the job. In

summary, employee job satisfaction includes how individual likes or dislikes the job or

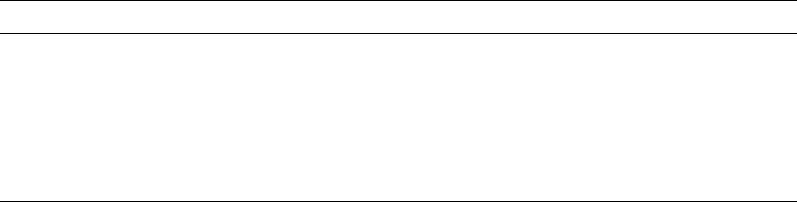

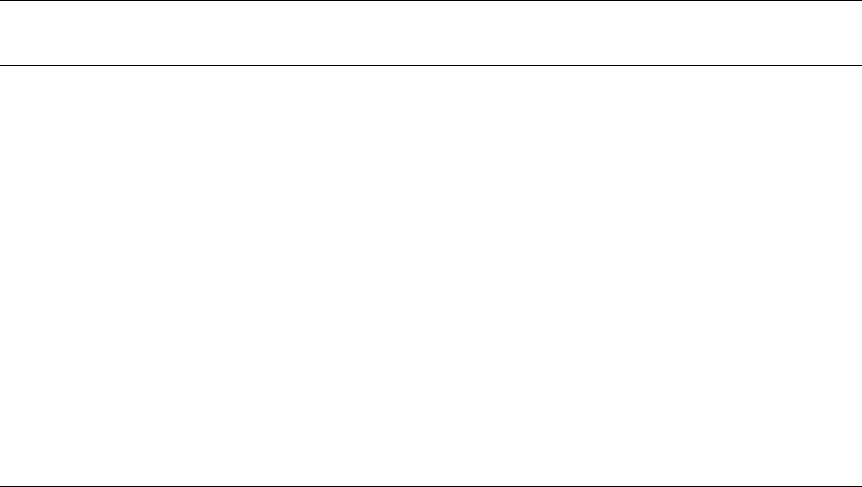

how individual assess his contentment towards his job as a whole or aspects of job. The