2023

Constant

Companion:

A Week in the Life of a Young Person's

Smartphone Use

Constant Companion:

A Week in the Life of a Young Person's

Smartphone Use

COMMON SENSE IS GRATEFUL FOR THE GENEROUS SUPPORT AND

UNDERWRITING THAT FUNDED THIS RESEARCH REPORT

Bezos Family Foundation

Jennifer Caldwell and John H.N. Fisher

Carnegie Corporation of New York

Margaret and Will Hearst

A Letter from Our Founder

Smartphones have become a constant companion in our teens' lives. From connection

with family and friends to entertainment and background noise, young people rely on their

smartphones for different types of mental health support, relaxation, and distraction—at

home and at school, and during the day and night.

This year, Common Sense has focused our research efforts on hearing directly from young

people about both the role and the impact of media and technology in their lives. This

report fills a gap in our understanding of how teens actually use their smartphones,

combining data from kids' phones themselves with feedback from our Youth Advisory

Council. And they told us that the draw of their smartphone is both complicated and

powerful. Here's what else we learned from this report:

• Teens are fielding a barrage of notifications from the apps on their phones. On a

typical day, participants received a median of 237 notifications. Of those, about a

quarter arrived during the school day, and 5% at night.

• School phone use is common, and policies are inconsistent. During school hours

almost all of the participants used their phones at least once, for a median of 43

minutes. But they also reported that policies about phone use in schools vary—some-

times even from classroom to classroom—and aren't always enforced.

• Smartphones both help and hurt sleep. Over half of participants used their phones on

school nights, often to listen to music to wind down or get to sleep. But sometimes

their days are so busy that they only get to relax with their phone at bedtime, and that

pushes sleep later.

The good news is, many young people reported they have grown savvier about their

phone's attempts to draw them in, and they're taking steps to protect their digital well-

being, like setting time limits and prioritizing certain types of notifications. But the

business model of these apps and devices hinges upon young people picking up their

phones and engaging with them as much as possible, and it's clear that teens are struggling

to set boundaries.

Research like this helps shed light on what young people are really doing on their phones,

and allows families, educators, and leaders to better understand where and when to

provide support. But the industry can take steps to recognize that young people need to

be able to use their phones for all of their important benefits but without the challenges

that negative content, persuasive design, and aggressive business models pose to digital

well-being.

At Common Sense, we will continue to provide parents, caregivers, educators, industry

leaders, and policymakers with the tools, resources, research, and information they need

to help kids build healthier relationships with the technology in their lives. And it's our

hope that this research allows for continued focus on youth voices in our mission to make

the digital world work better for kids everywhere.

James P. Steyer,

Founder and CEO

Suggested citation: Radesky, J., Weeks, H.M., Schaller, A., Robb, M., Mann, S., and Lenhart, A. (2023). Constant Companion: A Week in the Life of a Young Person's

Smartphone Use. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense.

Credits

Authors: Jenny S. Radesky, M.D., Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan Medical School

Heidi M. Weeks, Ph.D., Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Michigan School

of Public Health

Alexandria Schaller, B.A., Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan Medical School

Michael B. Robb, Ph.D., Former Head of Research, Common Sense Media

Supreet Mann, Ph.D., Director of Research, Common Sense Media

Amanda Lenhart, M.A., Head of Research, Common Sense Media

Copy editors: Christopher Dare and Jennifer Robb

Designers: Emely Garcia and Chris Arth

Acknowledgments: This research was supported by Common Sense Media. We thank Candice Odgers

for consultative assistance with survey measures. We also thank Andy Chen for

assistance collecting app store data.

Table of Contents

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Key Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Main Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

References. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Supplemental Tables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

1 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Smartphones entered the lives of children and adolescents in

2007. Compared to earlier devices (flip phones), smartphones

allowed more than just texting and taking photos. Young

people could now browse the internet, choose from thou-

sands of mobile applications ("apps") and games, and connect

immediately with their communities through social plat-

forms—from anywhere.

As internet speeds and computing power increased exponen-

tially over the past 15 years, smartphones have become even

more powerful and versatile, allowing livestreaming, multi-

player gaming, and creation and distribution of content. Over

a relatively short period of time, these handheld computers

have become a disruptive force in the lives of young people, in

positive and negative ways that adults who grew up with land-

lines may not fully grasp.

Getting a smartphone is now a rite of passage for most chil-

dren and adolescents in the United States. According to

Common Sense Research, 43% of tweens (age 8 to 12) and

88% to 95% of teens (age 13 to 18) have their own smartphone

(Rideout et al., 2022; Pew 2022). About half of U.S. children

get their first smartphone by age 11 (Rideout et al., 2022).

Young people describe a range of supportive and stressful

experiences with their smartphones—some wish they hadn't

gotten one so early, while also describing it as an appendage

that they cannot live without (Moreno et al., 2019). The deci-

sion of when to get a smartphone, and negotiations about

rules and boundaries around smartphone use, are frequent

sources of parental stress and family arguments (Mathes et al.,

2021; Francis et al., 2021; Hiniker, Schoenebeck, & Kientz,

2016).

Several factors contribute to young people's attachment to

their phones. First, it is developmentally appropriate for ado-

lescents to seek connection and feedback from their friends

and communities, and to want to do so on a frequent basis.

Children and adolescents have developmentally adaptive

curiosity about information, culture, entertainment, and

stories that help them make sense of their world.

However, the design and marketing choices made by technol-

ogy companies to meet their business objectives also make it

challenging for young users to separate from their smart-

phones. More time spent on mobile apps translates to more

advertising revenue and in-app purchases, so many apps

contain persuasive design features to encourage prolonged

engagement (Radesky et al., 2022; 5 Rights Foundation,

2021). These design features include encouragement of

content creation (so there is always more content to recom-

mend to users), reduction of friction (e.g., the swipe-up

movement that allows a user to easily move on to another

video), time pressure (e.g., notifications urging users to watch

a livestream before it stops), quantified reinforcers (e.g., likes,

shares, virtual currency), or algorithmic recommendations

that analyze a user's digital behavior to predict what they

might click on next.

Underlying these design features are marketing incentives to

keep young people on their phones—and ideally win their

brand alliance. Smartphones are an unprecedented marketing

vehicle because they are taken everywhere and provide

insight into users' daily behavior, preferences, and social net-

works. The data traces recorded by smartphones (such as

location, purchases, likes, and shares) allow businesses to

create user profiles, which can then be sold or used to earn

revenue through targeted advertising.

Considering the competing interests of 1) a business model

that prioritizes engagement and 2) a developing adolescent

human user with various passions, drives, and obligations, it is

not surprising that both young people and their parents com-

plain of feeling like they spend more time on their phones than

they intend (Pew 2022; James & Weinstein, 2022).

Smartphones are nearly ubiquitous in the life of U.S. adoles-

cents, but research on how they are used has been elusive.

This research typically relies on self-reporting of daily usage

habits, momentary reports (e.g., pinging participants through-

out their day to assess moment-to-moment changes in media

use), or asking young users what they experience through

their phones (e.g., social support or bullying; toxic or inspira-

tional content). However, if we want to interrogate the role of

Introduction

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 2© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

To that end, we enrolled 203 11- to 17-year-olds in the United

States to let us track their smartphone use for one week by

installing Chronicle, a study app (Radesky et al., 2020). This

app runs unobtrusively in the background and provides con-

tinuous data about which apps were used and when, how

many pickups and notifications occurred, and how much

smartphones were used during the school day and overnight

hours. The study was conducted with Android phone users

only, because Apple device tracking does not share with the

research community the names of specific non-Apple apps

that young people commonly use (e.g., social media apps,

mobile games).

After analyzing results, we reviewed them with 15 members

of the 2023 Common Sense Youth Advisory Council, a group

of 14- to 18-year-olds of various races/ethnicities and genders

who live in communities across the United States. These youth

advisors worked with Common Sense from January to May

2023, but their phones were not tracked as part of the study.

Through these conversations, we gained insights into the push

and pull that adolescents feel with their phones, with the ulti-

mate goal of imagining how smartphones could be designed to

support the agency of younger users.

Along with our main findings, this report includes relevant and

actionable takeaways for parents and policymakers, as well as

discussion prompts for talking with kids about their some-

times complicated relationships with smartphones.

smartphones—and all of their complex uses in the daily lives of

young people, from communication to entertainment, creativ-

ity, marketing, and productivity—then we need research

methods that measure the behavior of phones. This is possible

through the harnessing of data that is already collected by

technology companies and marketing firms to monitor smart-

phone users, but that is not typically shared with researchers

on an individual-user basis.

For this study, we used software to collect data from the

smartphones of a diverse sample of about 200 11- to 17-year-

olds. We then interpreted this data with assistance from an

advisory council of young people to understand the nuanced

relationships that young people develop with their

smartphones.

Our research aimed to address the following questions:

• How much time are preadolescents and adolescents

spending on their smartphones?

• Which types of apps do they use most frequently and for

the longest periods of time, and why?

• Are they accessing apps intended for older audiences?

• How many notifications are they receiving per day, and

from which apps?

• How much smartphone use occurs during school hours,

and why?

• How much smartphone use occurs at night, and why?

• How much tension or frustration are preadolescents and

adolescents experiencing about their smartphones, and

how do they manage this?

• Are there new insights about youth experiences and

practices with smartphones that could lead to better

design to improve young people's well-being?

3 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Key Findings

The key findings in this report combine

granular data about young people's smart-

phone use with teens' own interpretation of

the role that these devices play in their lives.

This unique perspective gives us a glimpse

into teens' relationships with their devices,

including the attraction that smartphones

and apps hold for teens, the corresponding

pressures, and the strategies they use

(whether barriers, rules, or friction) to

manage smartphone use in their day-to-day

experiences.

1. The smartphone is a constant

companion, both providing background

buzz and encouraging regular pickups

over the more than four hours of teen

smartphone use on an average day.

Smartphones are integrated into young people's lives in ways

that help them connect with friends, give their brain a rest, or

help them laugh and calm down during their busy days. On a

typical day, the participants in our study used their smart-

phones for a median of almost four and a half hours. However,

simply showing average daily smartphone duration across our

sample doesn't tell the whole story. Some participants used

their phones for only a few minutes per day, while others aver-

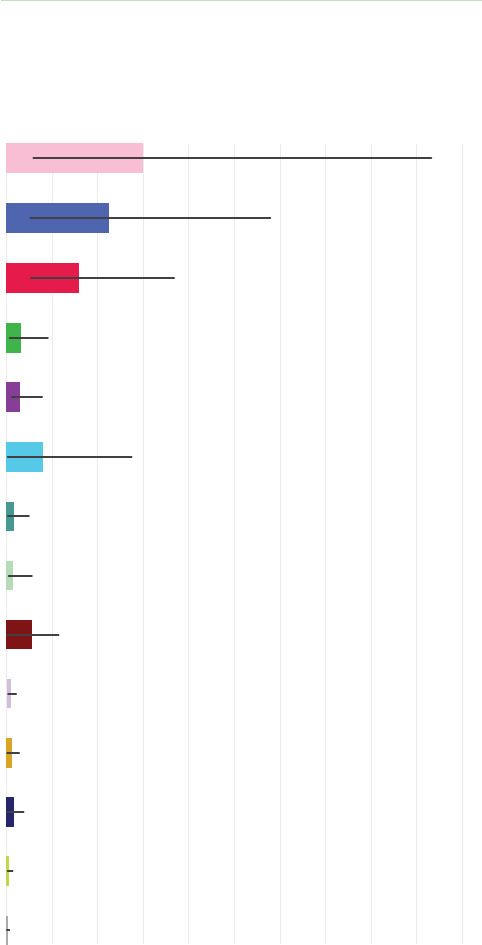

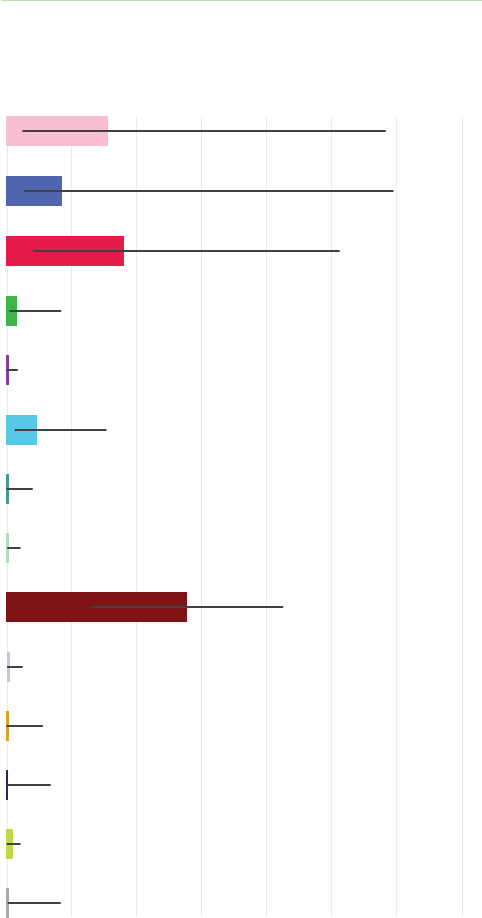

aged over 16 hours a day (Figure 1).

Adolescents' smartphone use doesn't always match adults'

narrative of "teens always staring at their screens." In addition

to more active use, some teens in our focus groups talked

about how they also use their smartphones to provide a back-

ground "buzz" by playing movies, videos, or music while they

do homework or laundry.

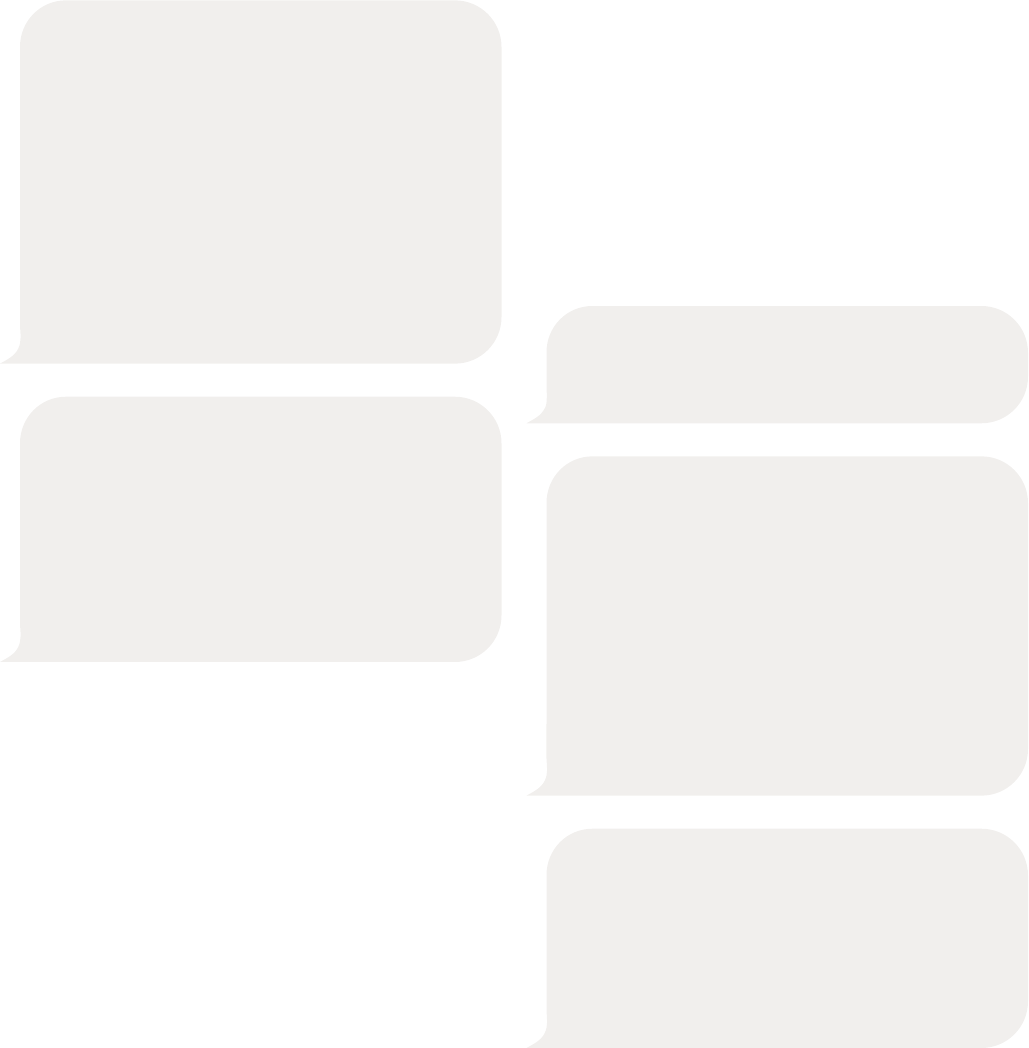

And for most of the teens in our sample, their smartphones

were close at hand and picked up and checked frequently

throughout the day—a median of 51 times per day, ranging

from two to 498 times per day. Younger participants (11- to

12-year-olds) tended to pick up their phones less frequently

each day, while adolescents (age 13 and older) were more

likely to check their phone over 100 times per day (Figure 2).

Teens in our focus groups told us that younger smartphone

users usually have more rules or restrictions placed on their

use, while older teens are given more independence as they

learn the appropriate time and place to use their phone.

Younger teens may be less likely to have peers with smart-

phones, and fewer friends to contact.

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 4© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

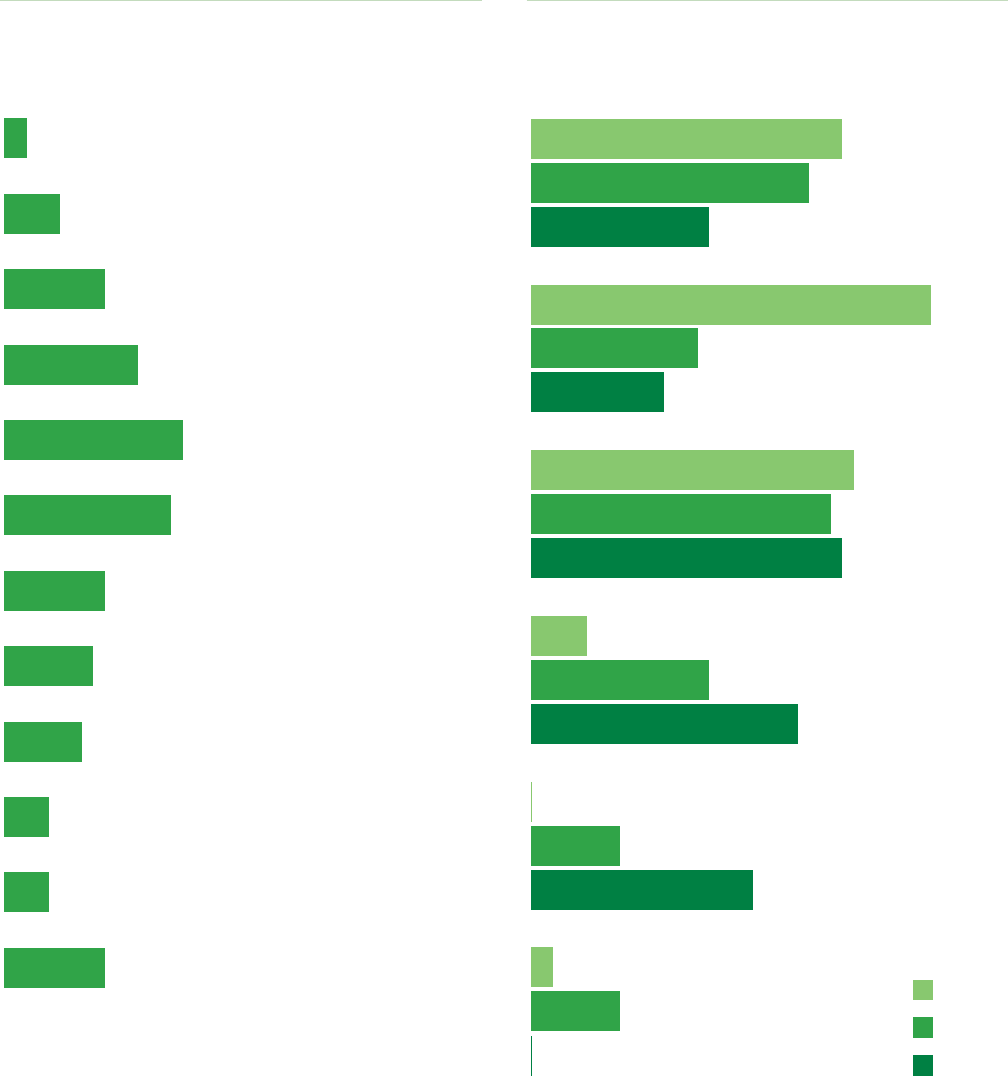

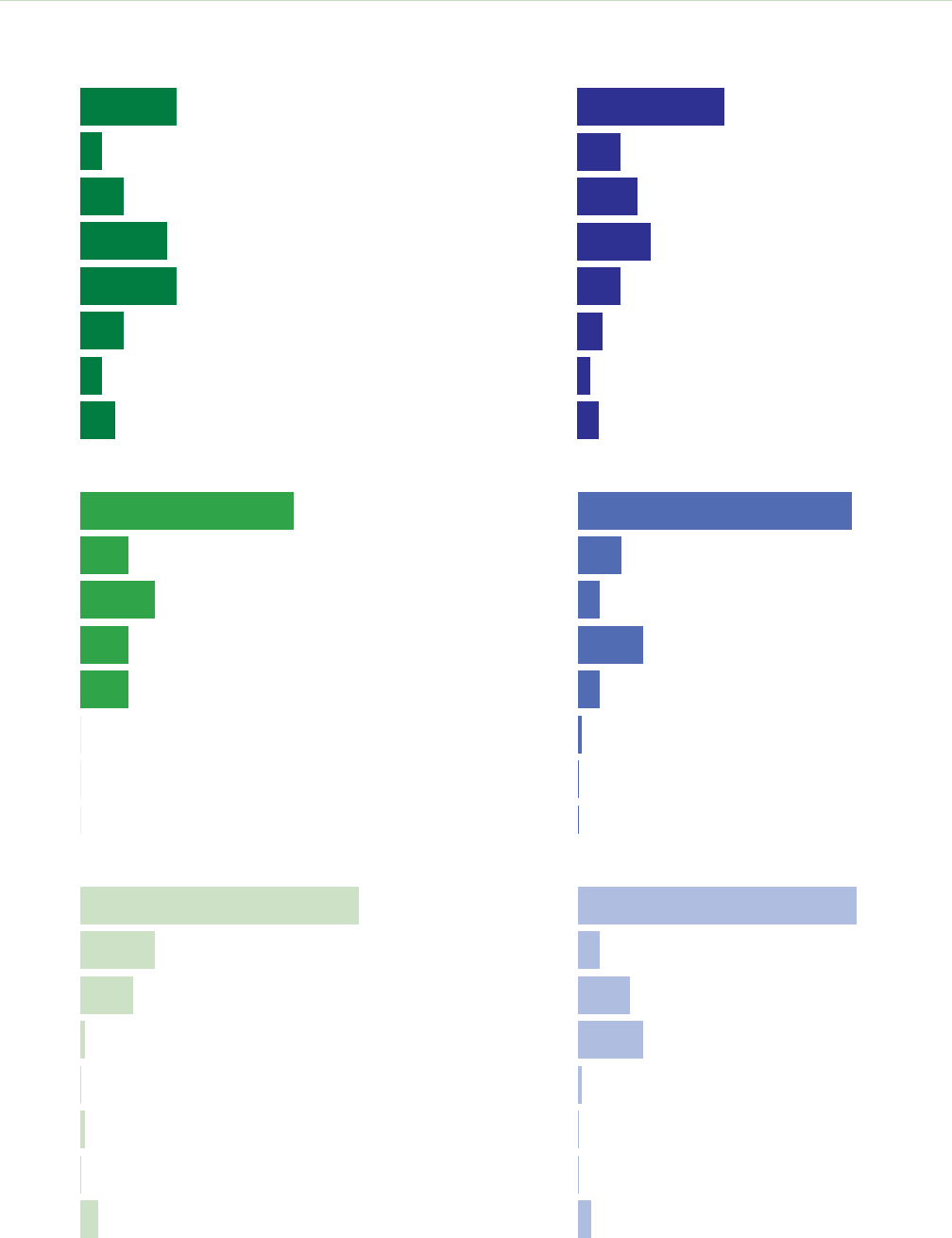

FIGURE 1. Distribution of average daily duration of

smartphone use

>10 hours

9-10 hours

8-9 hours

7-8 hours

6-7 hours

5-6 hours

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

0-30 min

9%

5%

2%

12%

16%

15%

9%

8%

7%

4%

4%

9%

FIGURE 2. Average daily smartphone pickups, by

participant age

26−50

0−25

16−17

13−15

11−12

28%

25%

16%

36%

15%

12%

51−100

29%

27%

28%

0%

>200

2%

8%

101−150

5%

16%

24%

151−200

8%

20%

0%

5 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

2. Phone use during school hours is

nearly universal but varies widely,

reflecting a patchwork of different

school policies.

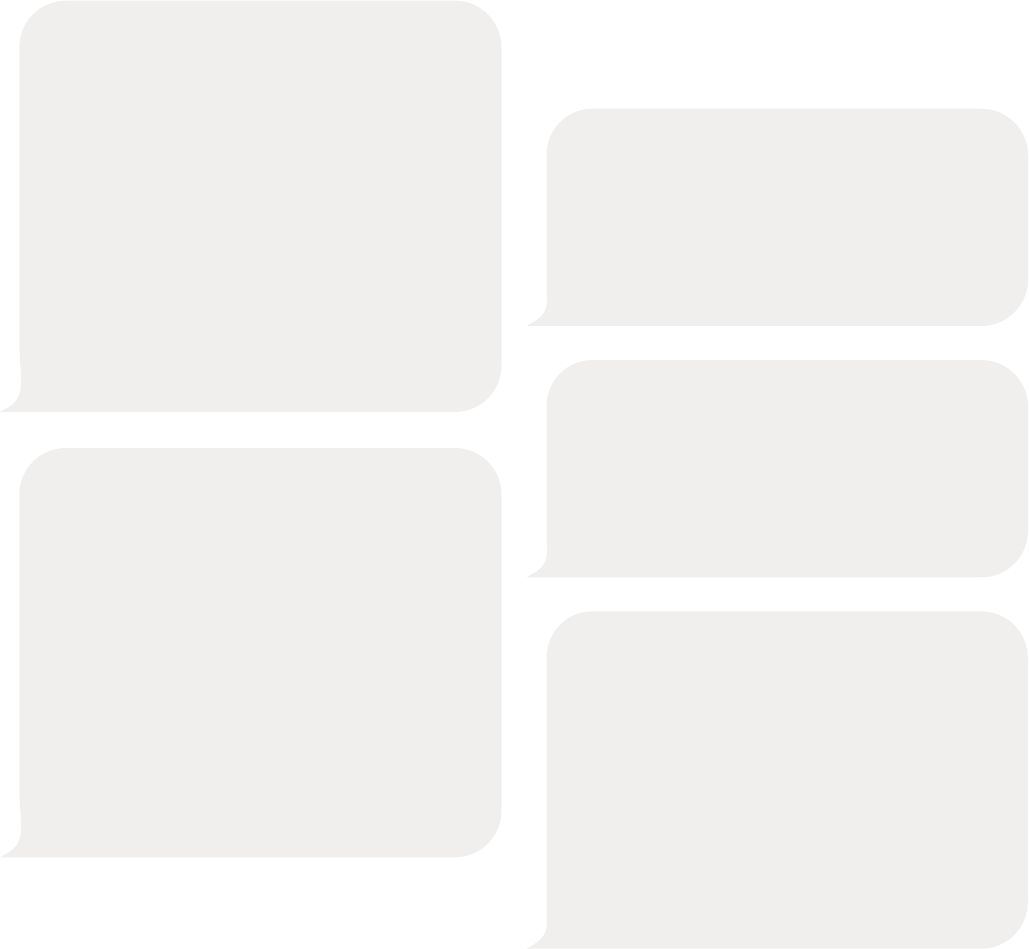

Smartphone use at schools is fairly widespread, and it

varies based on school rules, teacher and staff enforce-

ment, and student compliance. During school hours

(Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., excluding holi-

days), 97% of participants used their phones, for a median

of 43 minutes (ranging from less than one minute to six and

a half hours). The median number of pickups was 13 per

school day, ranging from less than one to 229. The app cat-

egories that took up the highest proportion of time during

school hours were social media (32% of smartphone use

during school hours), gaming (17%), and YouTube (26%),

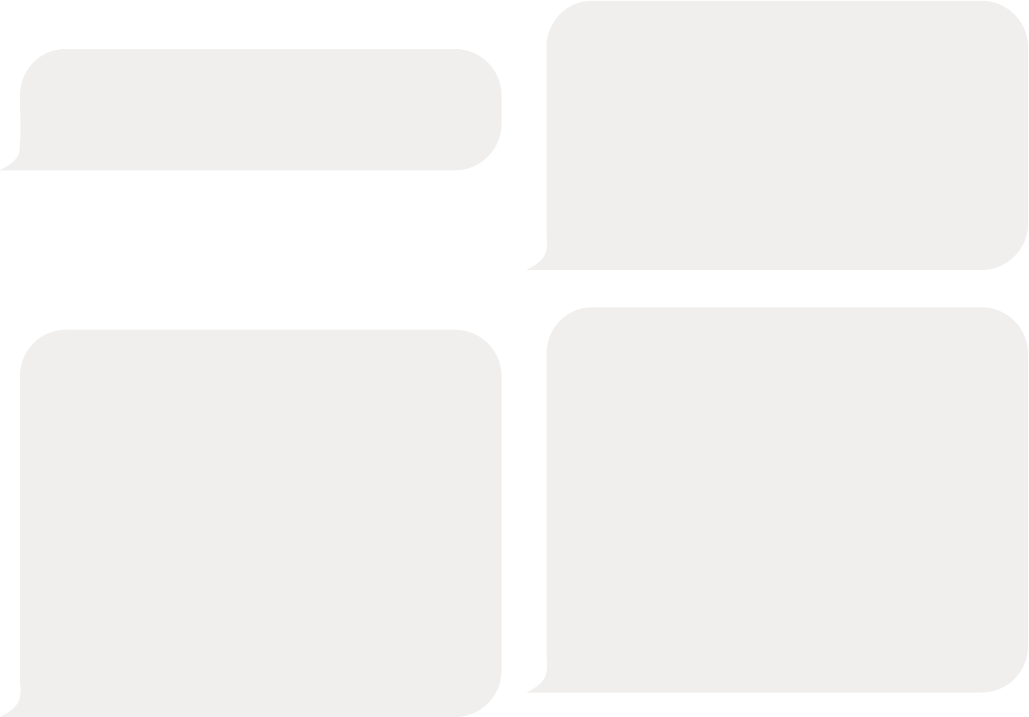

among participants who used those app categories (Figure 3).

Youth advisors told us that schools have a wide variety of poli-

cies, and variable enforcement within those policies, which

students may or may not follow:

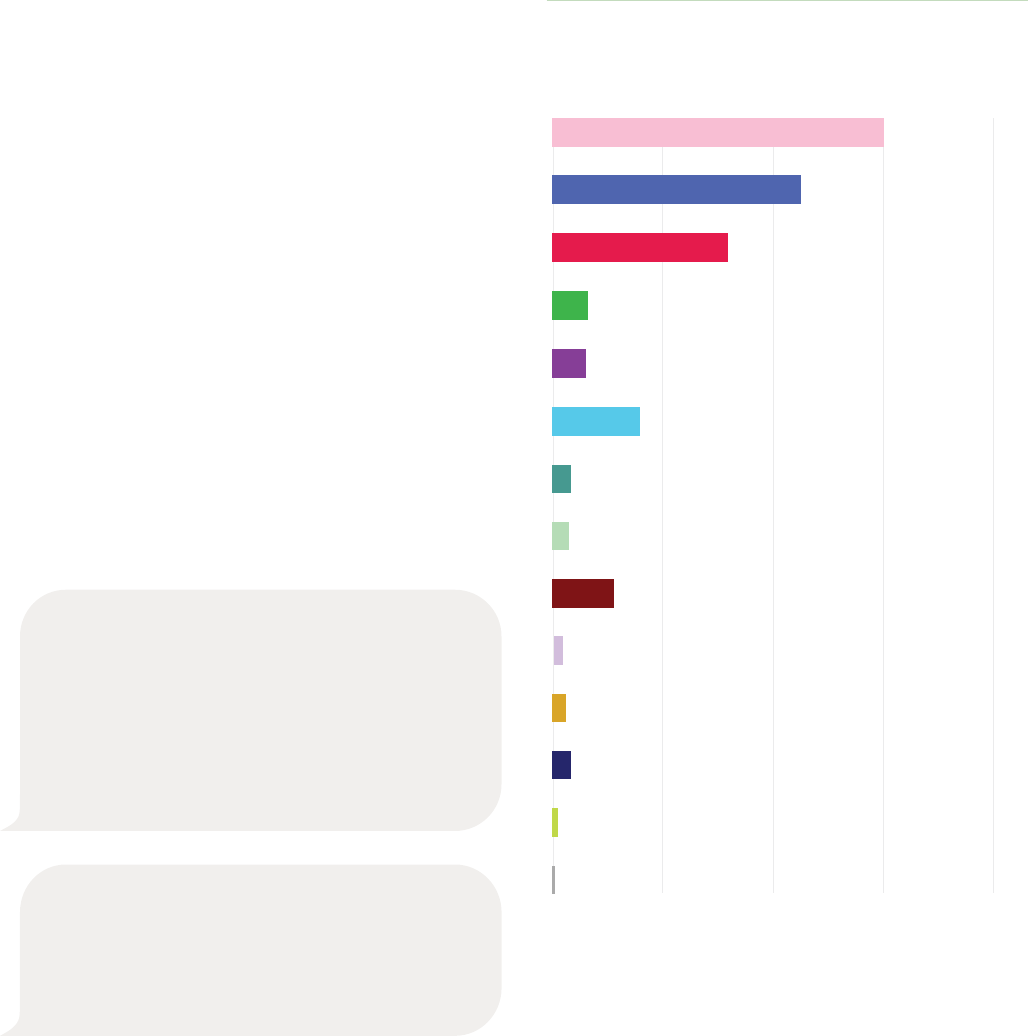

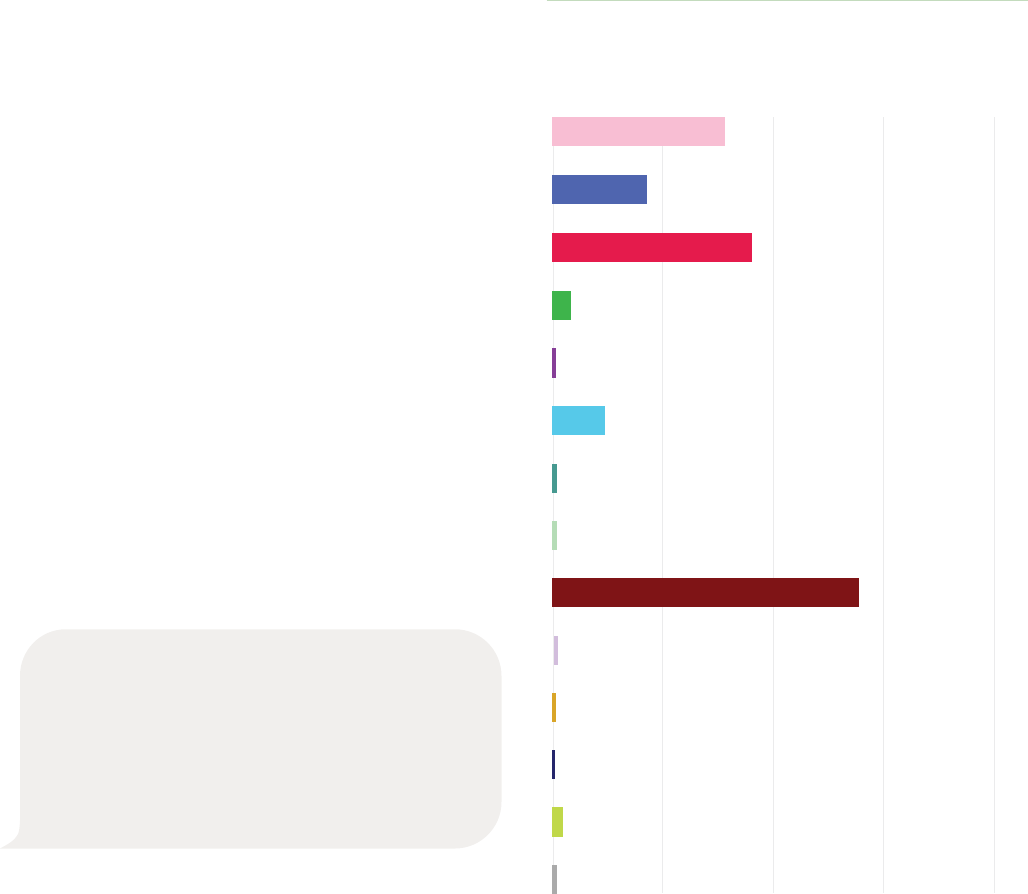

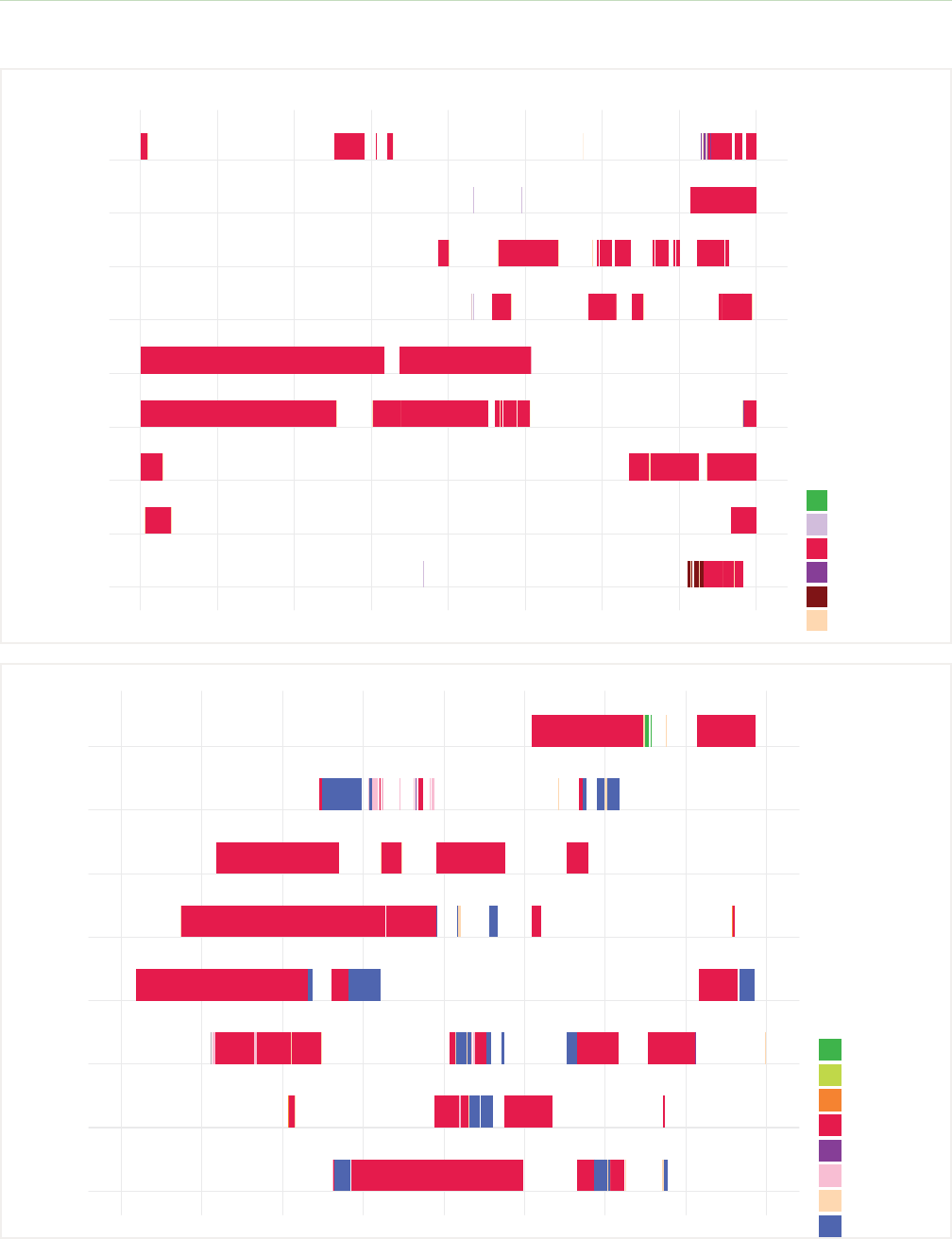

FIGURE 3. Median* duration of use of different smartphone

app categories during school hours**

*Median is the value that 50% of the users are under and 50% are over.

**Includes only participants who used that category of apps during specified

time frame.

Parent Controls (n=19)

Email (n=69)

Education (n=51)

Shopping (n=37)

Calls (n=132)

Reading (n=23)

Music and Audio (n=81)

Art and Photos (n=133)

Streaming Video (n=30)

Messaging (n=146)

Browser (n=150)

Gaming (n=119)

YouTube (n=111)

Social Media (n=126)

Average School Day Minutes (Median)

20100

For my school, we do have a phone policy and

we're not technically allowed to have it out during

class, but a lot of people do in spite of that. And

definitely, I think if you track kids at my school,

their phone usage, you would definitely see them

checking their phones, and then checking

Snapchat during class.

—10th grader

It's kind of up to teacher discretion. So at the

beginning of the year, they said it's not allowed,

but it's really up to each teacher whether they

allow it in the room or not. A lot of them do.

—11th grader

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 6© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

3. Notifications are plentiful, with

half of our participants receiving 237

or more per day. These interruptions

are both delightful and distracting,

leading many young users to feel the

need to manage what they get notified

of, and when.

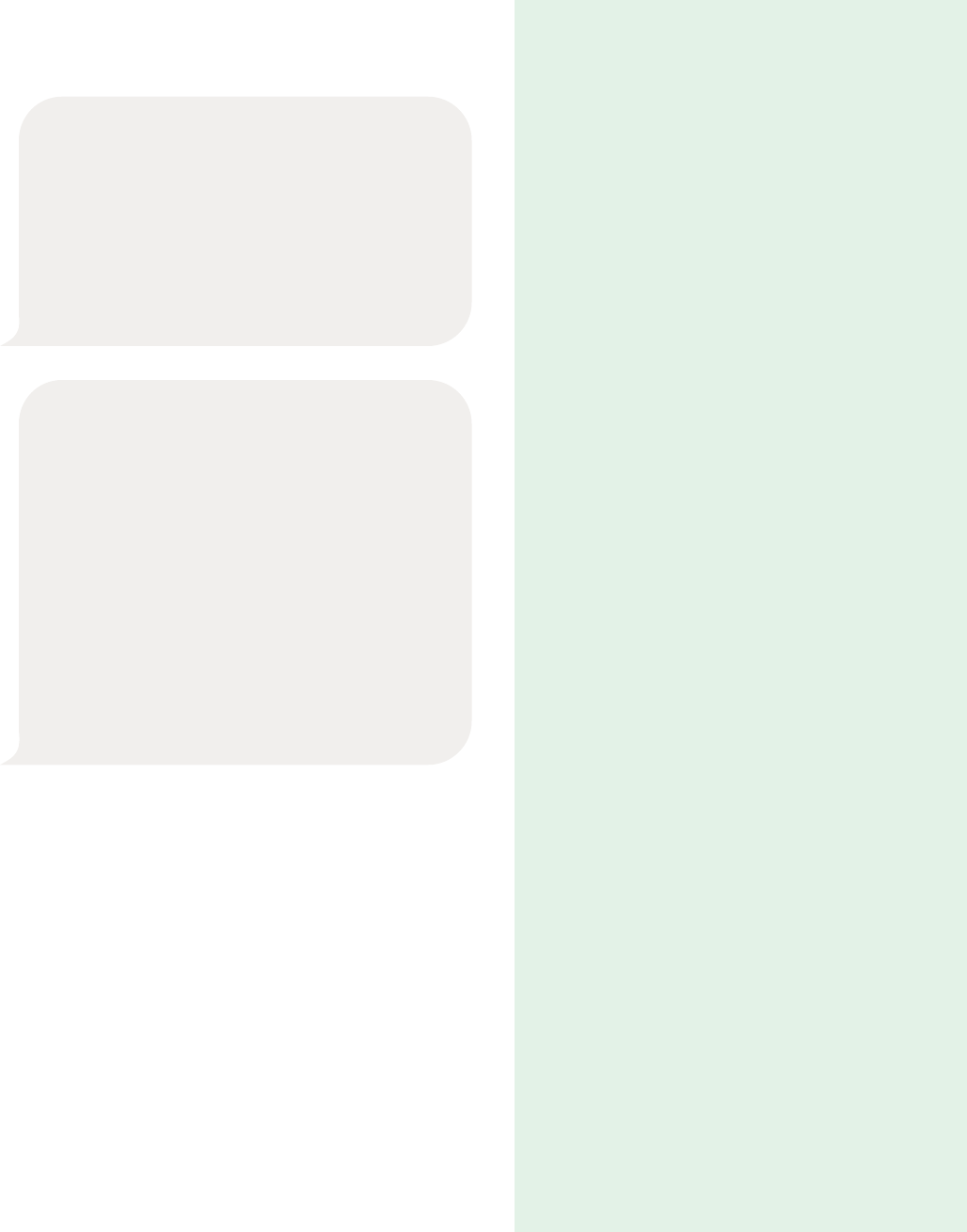

While phone pickups signify how often a user is engaging with

their phone, notifications show us how often a phone tries to

engage its user. On a typical day, participants received a

median of 237 notifications. Of the notifications delivered to

their phone, participants saw or engaged with about a quarter

(median 46 per day). Notification frequency varied widely,

with maximums of over 4,500 delivered and over 1,200 seen

(Figures 4 and 5).

About a quarter (23%) of notifications arrived during school

hours, and about 5% during school night hours, suggesting

that phones and apps could do a better job of eliminating

unnecessary notifications at times of day that are more dis-

ruptive to young people. Very few participants received no

notifications at all during school hours or school night hours.

Because notifications are so numerous and occur day and

night, they require management by young users. Our youth

advisors described different approaches to managing these

interruptions. They said it was essential to filter or block noti-

fications, particularly from "spam" content, favoring

notifications of direct messages (DMs) from people.

Snapchat and Discord ranked highest in the number of notifi-

cations sent to participants in a typical day, with some

participants receiving hundreds of messages from these plat-

forms. But our youth council members noted that they've

become savvy to the ways in which some apps try to pull them

in with frivolous notifications.

Yeah, for me, I have notifications on for the apps

that are messaging apps, but then for the other

ones, I don't have notifications on for YouTube or

Instagram … For me, I don't like the notifications

that just tell you to go back on the app or just

something random like that, like an update or

something. I don't really care about those ones.

But the ones I do like getting are the ones that are

from the messaging apps, like if someone sends

me a text, I wanna know what it says.

—10th grader

FIGURE 4. Average daily notifications received by

smartphones

FIGURE 5. Average daily notifications seen by the user

>500

401-500

301-400

201-300

101-200

0-100

20%

20%

23%

9%

9%

20%

>200

151-200

101-150

51-100

26-50

0-25

28%

24%

21%

12%

7%

8%

7 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

I also think the TikTok algorithm is just way better

than any of the others. Even Instagram reels and

then YouTube Shorts is like the same thing as

TikTok, but the algorithm for TikTok is just way

more addicting, I feel like [it]… draws you in more,

and it also adapts really quickly. So if I skip a few

of the same type of video, it'll stop playing that

pretty quickly … I think it just happens naturally.

You just scroll without really looking at a certain

type of video a few times and then you'll see it

adapts and gives you some other type.

—11th grader

4. TikTok is irresistible, offering

bite-size pleasure and low-friction

interaction that quickly adapts to

the user's interests or mood.

TikTok was one of the most popular and longest-duration apps

used in the sample of 11- to 17-year-olds whose phones we

tracked. TikTok was used by 50% of our participants, for a

median of one hour and 52 minutes per day. Compared to

other social media apps, TikTok users were more likely to

spend several hours per day using it (upwards of seven hours

a day), often during school hours and overnight. In contrast,

the longest amount of time spent on Snapchat and Instagram

was around three hours per day.

Youth advisors explained to us that TikTok provides an experi-

ence that other social or video-sharing platforms don't. TikTok

was described as "easy" because videos simply start to play—

the user doesn't have to make any decisions, so there's no

friction. Adolescents we talked to said that the TikTok algo-

rithm "knows" them so well, they can expect that they will

likely find something fun to watch. If the user isn't interested

in the video that starts to play, the app quickly adapts to some-

thing more engaging or that fits their mood or desires. Finally,

the videos are short, so they provide small doses of pleasure

when young people need a break but don't have a lot of time.

Then TikTok, I honestly feel just because it's so

easy to feel, 'Oh, I only have 10 minutes. Let me

get onto TikTok right now 'cause I don't really

have time for anything else.' Because it provides

kind of instant entertainment, you don't really

have to go in, like on YouTube you have to go in,

you have to search for something, you have to

find a video that you wanna watch. And on

TikTok it's really just there. You can open it kind

of whenever you want. And even on a short

amount of time, you can still watch at least two

or three videos.

—11th grader

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 8© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

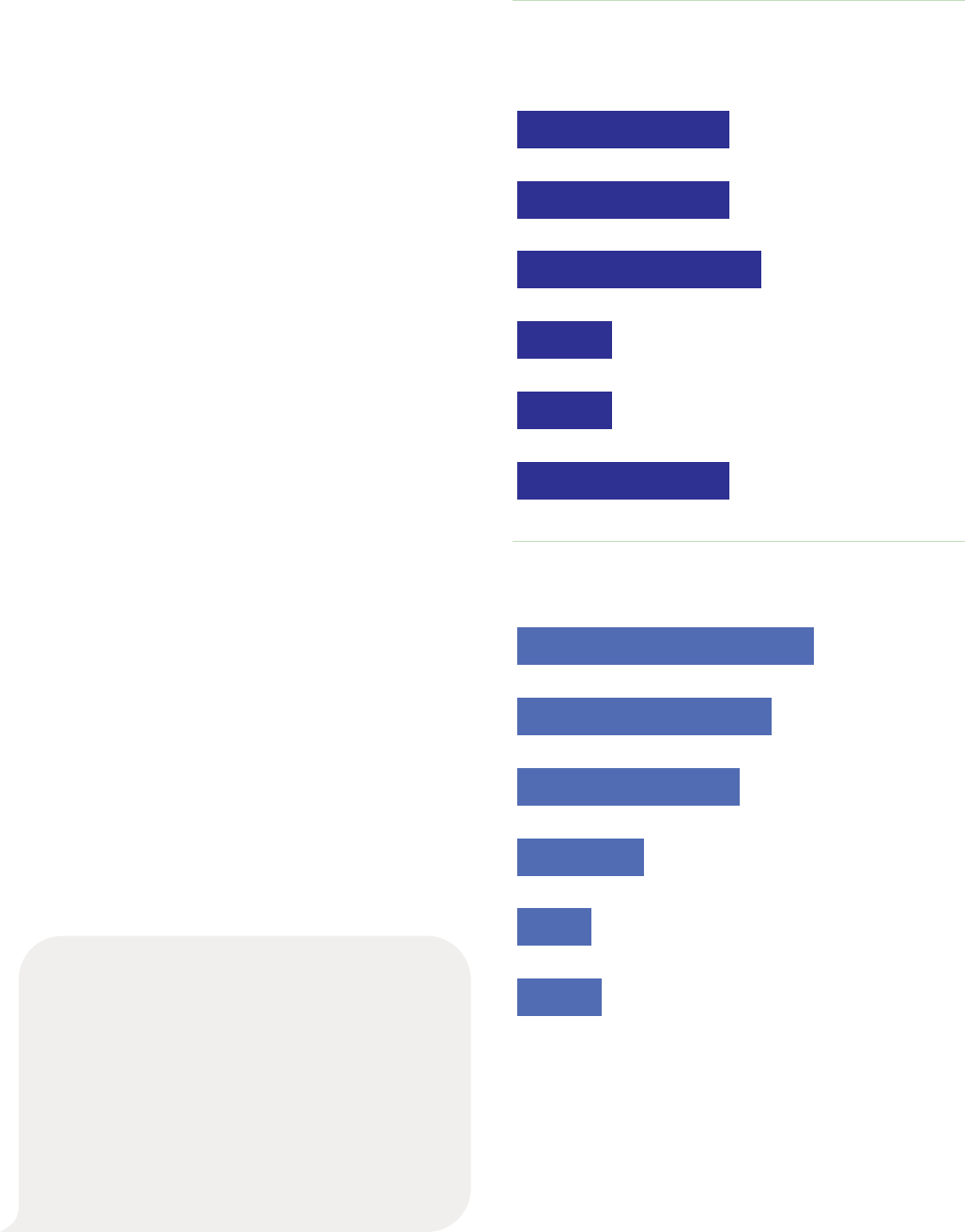

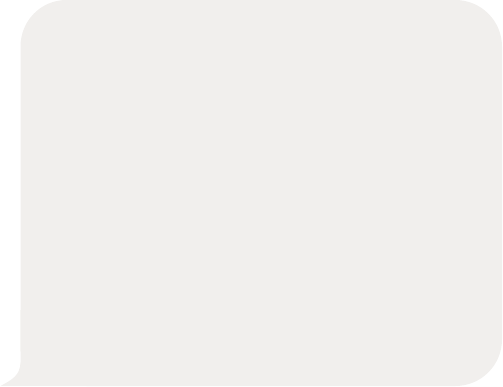

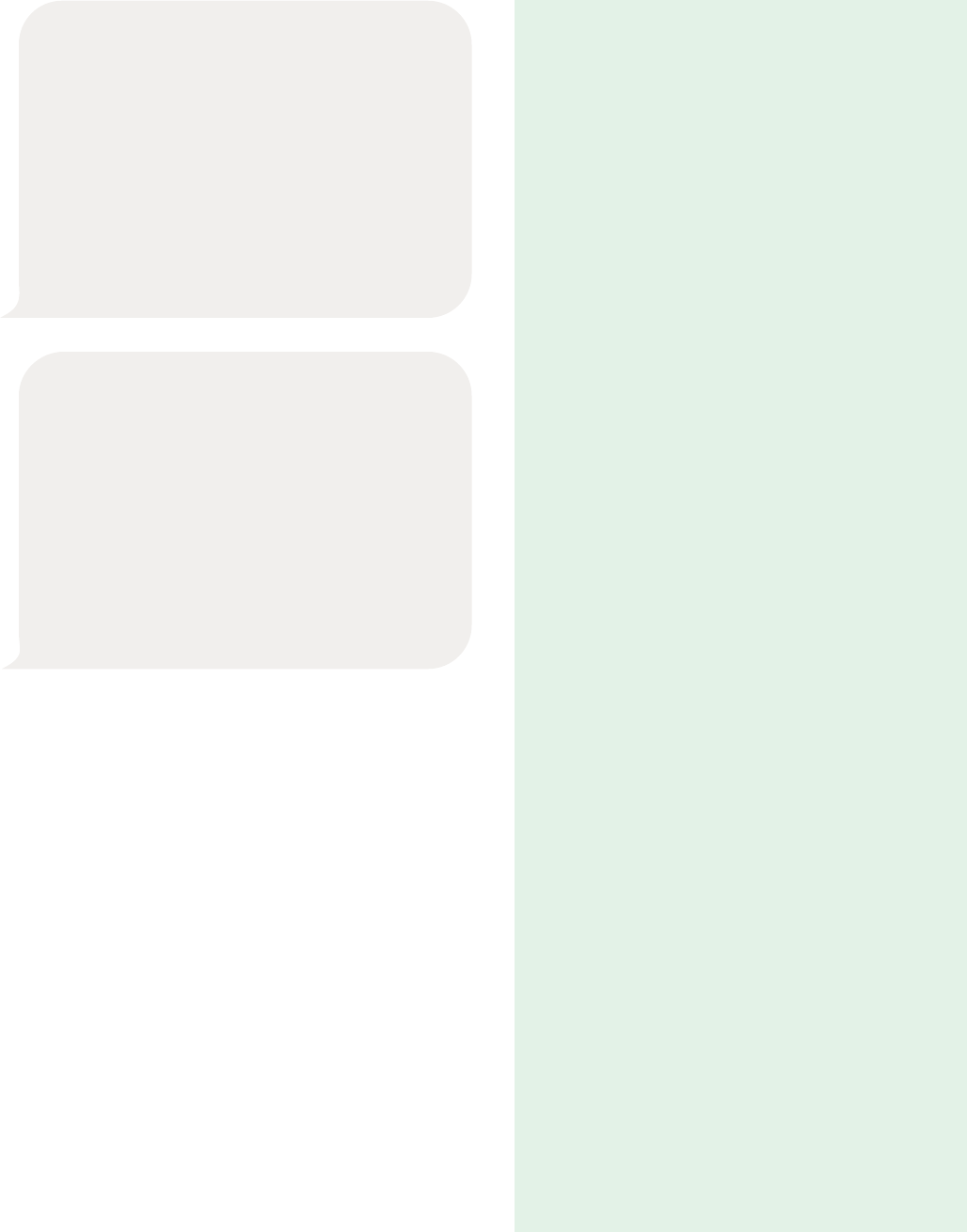

FIGURE 6. Median* duration of use of different smartphone

app categories during school nights**

*Median is the value that 50% of the users are under and 50% are over.

**Includes only participants who used that category of apps during specified

time frame.

Parent Controls (n=3)

Email (n=11)

Education (n=5)

Shopping (n=11)

Calls (n=9)

Reading (n=6)

Music and Audio (n=18)

Art and Photos (n=24)

Streaming Video (n=14)

Messaging (n=27)

Browser (n=49)

Gaming (n=32)

YouTube (n=54)

Social Media (n=60)

Average School Night Minutes (Median)

20100

5. Over half of teens used their phones

overnight on school nights, primarily

for social media, gaming, or YouTube.

We defined school night usage as any use Monday through

Friday during the hours of midnight to 5 a.m. (excluding holi-

days). Over half of participants (59%) used their phones on

school nights, with a median of about 20 minutes per night,

although use ranged from less than a minute to five hours.

Similarly, 67% of participants had pickups on school nights,

with a median of one per night, though at least one participant

picked up their phone 18 times on a typical school night.

App categories that took up the highest proportion of school

night use included YouTube (47% of smartphone usage on

school nights), social media (39%), gaming (29%), and reading

(18%), among participants who used those app categories.

YouTube appeared to be the longest-running app due to

several participants running it overnight, likely with music or

white noise playing. TikTok was also commonly used in the

overnight hours on school nights, but youth advisors reported

that TikTok can be overstimulating and lead to difficulties in

falling asleep.

I might say that for certain apps, like TikTok,

it's really hard to fall asleep once you use it close

to when you're gonna go to sleep. I can't use it

within an hour, or else I'd struggle … and then

I'll just get back on the app 'cause I'm not

sleeping anyway.

—10th grader

9 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

For me, even throughout the day, I keep 'do not

disturb' on, not even because I wanna not

respond to people or anything like that. I like

being able to not have my phone buzzing, but

being able to click on ... I don't know if I can show

you guys, but like here, you see this. Like you

have to click on that to see all of the notifications

that people have sent or everything that ... All the

notifications that you would have gotten if you

weren't on 'do not disturb.' For me, I like the extra

step because then it's like me having to do more

work to be on my phone, and I don't know, I feel

like it's a little strategy for me.

—11th grader

6. Smartphones can allow access

to age-inappropriate experiences,

including social media for kids under

13 and apps with mature/adult-only

ratings.

Of 85 participants who were under age 13, 68% used social

media apps, and they all used at least one app rated "Teen" or

higher. The most popular social platforms among 11- to

12-year-olds were TikTok (used by 47%), Snapchat (31%),

Discord (25%), Instagram (16%), Facebook (16%), and

Pinterest (14%).

In addition, almost half (45%) of our participants used apps

with mature (17+) or adult only (18+) ratings, such as Pornhub,

fantasy sports/betting apps (Yahoo Fantasy Sports & Daily,

Sleeper Fantasy Football), Telegram, Reddit, Parler, 4chan,

casino games, or violent games such as Call of Duty.

A small number (14) of participants used social media apps

with risky features, like being able to connect with strangers

for messaging, sending photos, or video chat. Although these

riskier social media apps did not take up as much time as more

mainstream social media apps, even brief use might lead to

problematic interactions with adults.

7. Young users admit they have

challenges managing their technology

use, but through steps like curation and

adding friction, they're working on it.

In addition to tracking their phones, we surveyed our 203

participants to ask whether they had any problems managing

their technology use. Over two-thirds of these 11- to 17-year-

olds said they "sometimes" or "often" find it difficult to stop

using technology, use technology to escape from sorrow or get

relief from negative feelings, and miss sleep due to being on

their phone or the internet late at night. These impacts may be

due to the natural pull that adolescents feel toward their social

contacts through their phone, but the engagement-prolonging

design of apps and platforms also likely contributes.

Interestingly, our youth advisors described ways of adding

friction to their phones to try to use them more intentionally:

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 10© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

11 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Study design

A diverse sample of 203 U.S. preadolescents (ages 11 to 12)

and adolescents (ages 13 to 17) with their own smartphones

were recruited by Horowitz Research between August and

November 2022 (see Table 1). Parents and caregivers of

tweens and teens were contacted with brief information

about the study, and if interested, provided informed consent

for the child and shared the child's email address. Children

were then contacted by email and provided online informed

consent before completing a baseline questionnaire and

installing the Chronicle app (Methodic, Inc) onto their smart-

phone. Eligibility criteria included: 1) ages 11 through 17; 2)

speaks English or Spanish fluently enough to complete

informed consent and surveys; 3) has their own Android

(version 6.0 or above) smartphone (e.g., Samsung, Google

Pixel, Motorola, etc). iPhone users were not included because

data collection access for detailed app usage (i.e., names of

specific apps such as YouTube, Snapchat, etc.) was not avail-

able for researchers at the time of data collection. The study

was approved by the University of Michigan IRB.

Baseline surveys

Parents reported their educational attainment, household

income, and their child's race/ethnicity. Child participants

completed a brief online survey that included the Technology

Impairment Scale (six items, alpha = 0.76, Burnell & Odgers,

2023, adapted from Meerkerk et al., 2009) which assesses

compulsive technology use or interference with daily activi-

ties (e.g., Do you feel restless, frustrated, or irritated when you

cannot access the internet or check your mobile phone? Do you use

technology to escape from your sorrow or get relief from negative

feelings?) on a response scale of 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 =

often.

Mobile device tracking

Participants were instructed on how to install and set up the

Chronicle app and keep it running on their device for nine

complete days. This app was developed with NIH funding,

pilot-tested and validated against pen-and-paper logs of

smartphone use, and has been used in child and parent popu-

lations (Radesky et al., 2020). After nine days, participants

were contacted and prompted to uninstall Chronicle and data

were exported from the Methodic Chronicle dashboard.

Chronicle provides timestamped data about which app is

running in the foreground and when pickups and notifications

occur, but does not collect information about contacts,

message content, which websites are visited, or what content

is viewed on platforms. In the informed consent form, partici-

pants were provided clear explanations of what data would be

collected, how it would be used, and how soon it would be

deleted.

Data cleaning and inspection processes were used to identify

any missing gaps in smartphone data (e.g., no data for >12

hours) and reduce the duration of apps that sometimes run

long but are not true usage (e.g., launcher, screen saver, alarm

clock). Some participants' data crossed two time zones, indi-

cating that they traveled during data collection, so we

removed the time zones that occurred on fewer days before

analyzing time-stamped data. We visually inspected all over-

night data to ensure that it showed data characteristics of true

usage (i.e., rather than data irregularities that occasionally

occur). Chronicle data was then processed to calculate hourly

and daily duration, pickups, and notifications, as well as dura-

tion and notifications for popular apps and app categories.

Notification and pickup data were not available for four par-

ticipants with older versions of the Android operating system.

Data for each participant were also visualized using R.

App categorization

We pulled data from the Google Play store API corresponding

to each app package name, including the app category (e.g.,

gaming, photography, shopping, social) and content rating

(e.g., Everyone, Teen, 17+, 18+/Adult). Apps that could not be

found on the Play store were manually categorized. We col-

lapsed or expanded some categories to reflect the main types

of apps used by 11- to 17-year-olds. For example, "communica-

tion" apps were recategorized into more precise categories

that reflect different uses, such as calls, email, or chat/messag-

ing. We categorized any app as Social Media if it involved a

non-SMS platform that facilitated the exchange of text, video,

and photo content with interaction by users (e.g., Snapchat).

However, we separated YouTube into its own category (includ-

ing YouTube, YouTube Kids, and YouTube TV) because of the

unique usage patterns YouTube has shown in our prior work

(e.g., Radesky et al., 2020).

Methodology

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 12© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

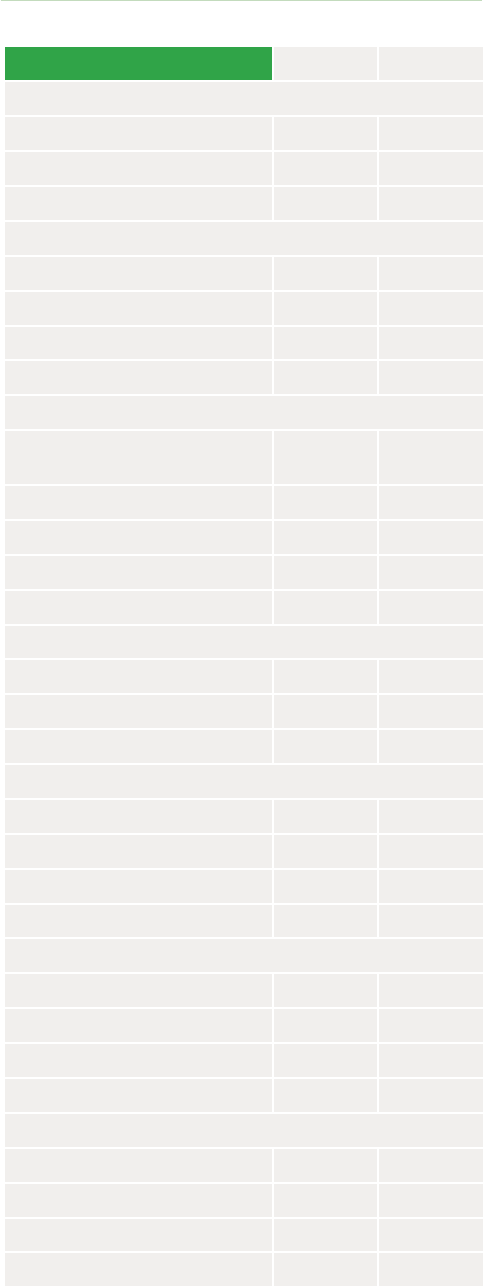

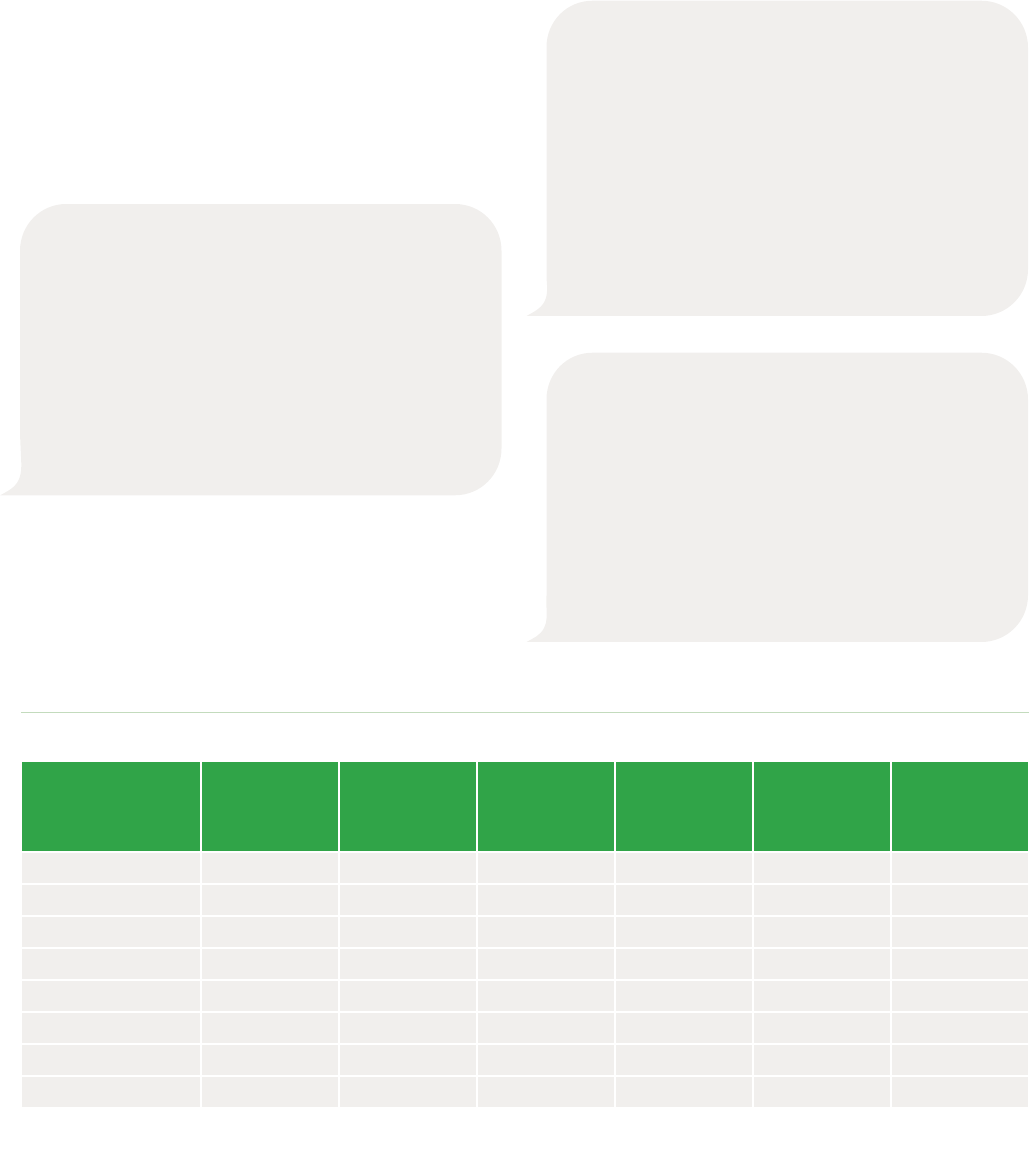

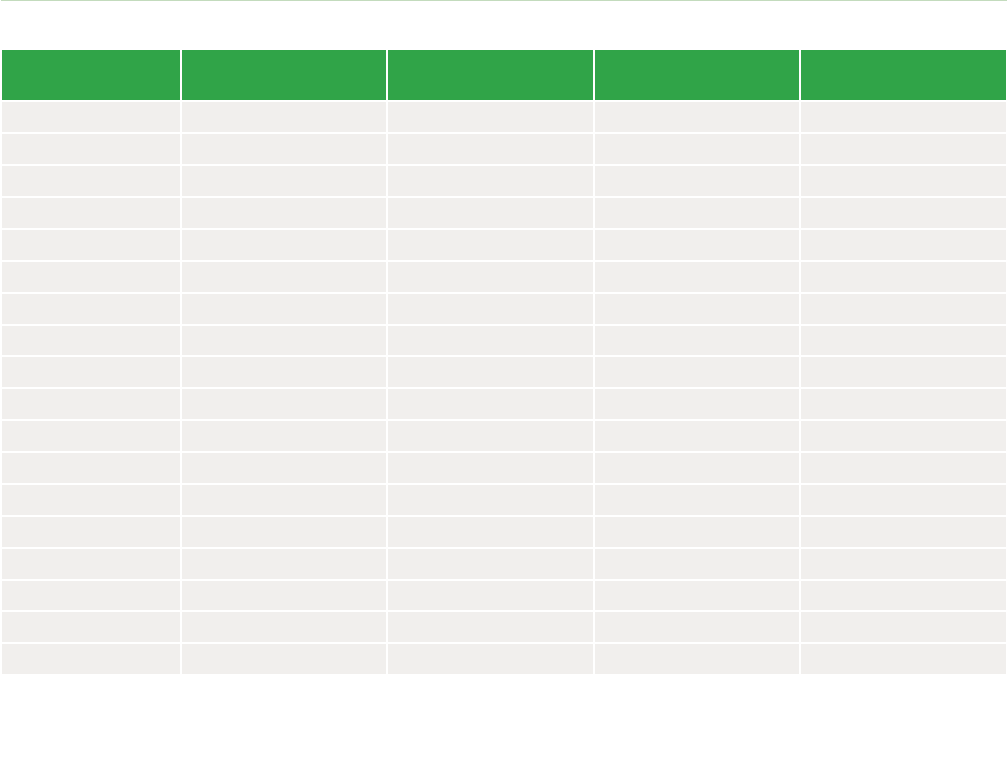

TABLE 1. Participant characteristics

Characteristic N %

Age category

11 to 12 85 41.9%

13 to 15 93 45.8%

16 to 17 25 12.3%

Gender

Female 89 43.8%

Male 112 55.2%

Nonbinary 1 0.5%

Other/prefer not to answer 1 0.5%

Race/Ethnicity

Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific

Islander

20 9.9%

Black or African American 39 19.2%

Hispanic/Latino/a/x/e 44 21.7%

Some other race 9 4.4%

White 91 44.8%

Household annual income category

<$50,000 71 35.5%

$50,000 to $99,999 77 38.5%

$100,000 or more 52 26.0%

Respondent parent education

High school/technical school or less 31 15.4%

Some college 55 27.2%

College degree 73 36.1%

More than a college degree 43 21.3%

Children in household (including participant)

1 67 33.0%

2 67 33.0%

3 41 20.2%

4 or more 28 13.8%

Respondent parent marital status

Married or living with a partner 146 71.9%

Separated or divorced 21 10.3%

Single 33 16.3%

Widowed 3 1.5%

Data analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses of the average daily dura-

tion of use, number of pickups (defined as the number of times

the screen turned on due to a user action), and number of

notifications. Notification data from the Chronicle app

included both notifications delivered to the smartphone

(regardless of whether the notification was audible or

silenced, as Chronicle does not collect that information) as

well as notifications seen by the user (indicating that the noti-

fication was interacted with by the user or appeared when the

user had the phone screen on). Notifications are delivered by

a wide range of apps, from utilities to texting apps, so duration

and notification data were also analyzed for particular app

categories and individual apps popular within the sample (e.g.,

TikTok). If a participant did not use their phone on a given day,

that day was excluded from analyses, so that the estimates

reflected what tweens and teens did during typical days of

use. We also segmented estimates of duration and pickups

into school hours (Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 14:59

p.m., excluding summer/holidays), or school overnight

(Monday through Friday, 12 a.m. to 4:59 a.m., excluding

summer/holidays) period. We calculated the number/percent-

age of participants who used app categories, specific common

social media apps and video games, and whether participants

endorsed positive or negative online experiences or different

technology impairment symptoms.

We used Chi Square and Kruskal Wallis bivariate tests to

study associations between smartphone usage variables and

age range (11 to 12, 13 to 15, and 16 to 17).

Post-analysis youth focus groups

Fifteen members of the 2023 Common Sense Youth Advisory

Council participated in four separate online focus groups with

the goal of helping the research team interpret and contextu-

alize findings from smartphone data. Parents or guardians of

Youth Advisory Council members had provided consent for

their children to participate, and members provided verbal

consent for audiotaping of Zoom focus groups, which were

then transcribed. First and last authors then reviewed themes

that arose from these groups and selected quotes for the

current report that aided with interpretation of findings from

a youth point of view.

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 14© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Main Findings

How much time were

preadolescents and adolescents

spending with their smartphones?

Time spent with smartphones, or any digital media for that

matter, can mean a variety of things. One hour of smartphone

use might mean an hour laughing with friends, messaging

about homework, consuming influencer content on social

platforms, responding to harassing comments, or getting lost

in a video game. Time spent with a smartphone might find an

adolescent user fully engaged, or might reflect apps running in

the background while the user multitasks. Therefore, these

results regarding smartphone time are the most basic

measure of a young person's relationship with their phone;

however, they hint at how pervasively a phone occupies a

teen's time on a typical day.

When averaged across all days their smartphones were

tracked, participants used their phones for a median of about

four and a half hours per day, but there was a wide range of

usage among different teens as shown by the duration catego-

ries in Figure 1. At the high end, almost 10% of participants

used their smartphones for 10 or more hours per day on

average.

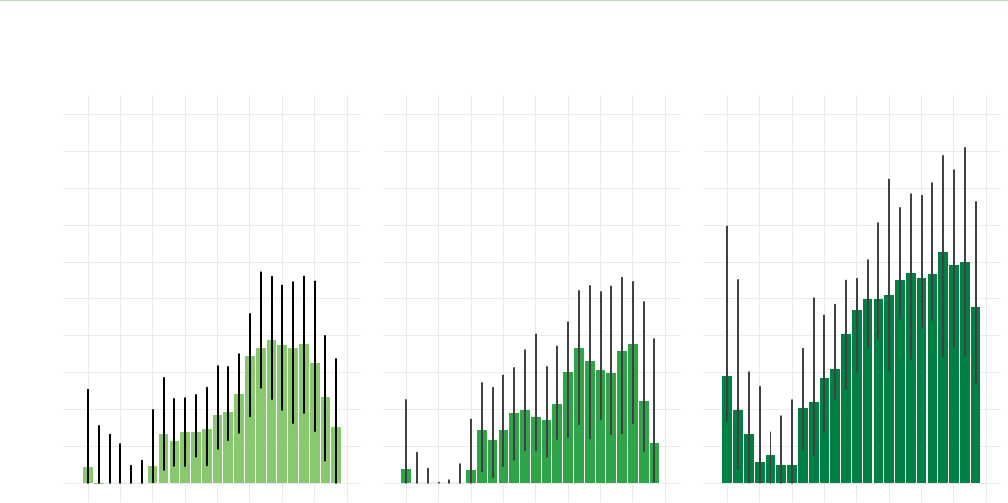

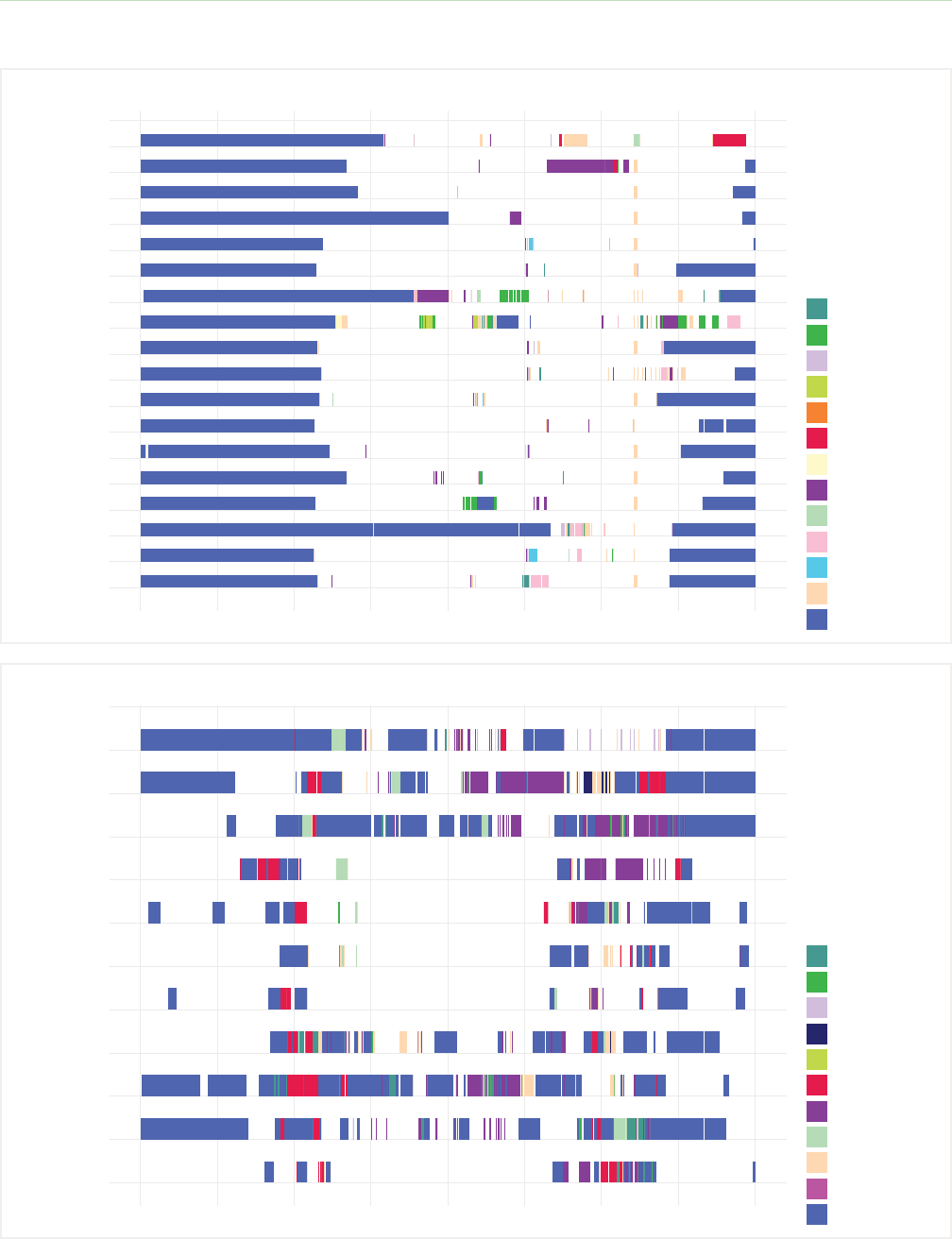

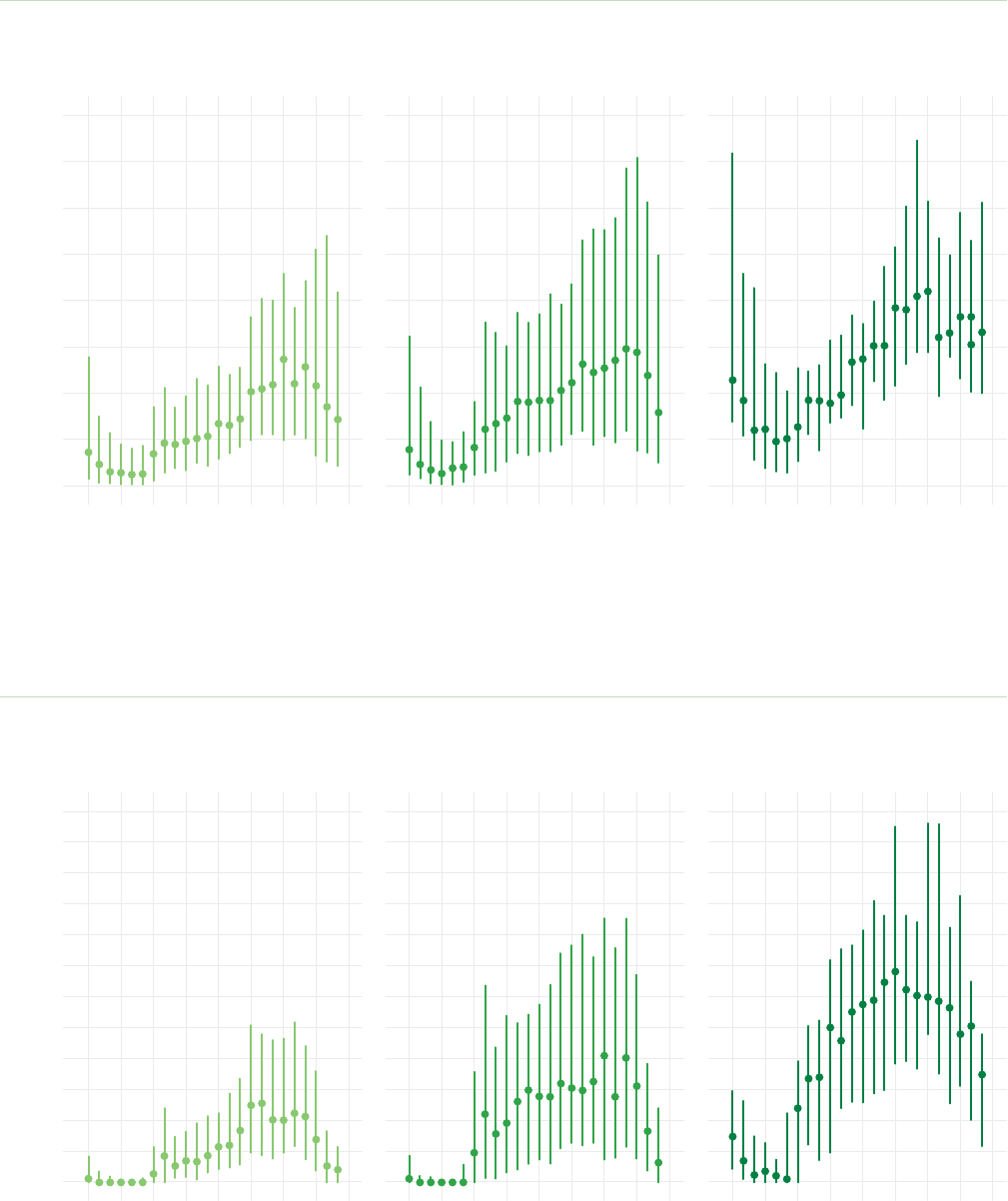

Hour-by-hour averages of smartphone use are shown in

Figure 7. Across all 203 participants, it is clear that the peak of

usage occurs in the afternoon and evening hours. Our youth

advisors stated that their smartphone is often by their side

after school, while doing homework, or when trying to wind

down before bed. Compared to younger participants, more

older teens (16- to 17-year-olds) used their phone in the over-

night hours.

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

0

10

20

30

40

50

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

Average Duration in Minutes (median [IQR])

Time of Day

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

16-1713-1511−12

*Median is the value that 50% of the users are under and 50% are over. IQR is the Interquartile Range, which is the middle 50% of users, with 25% of users under the first value

and 25% of users over the second value. Bar shows the median value; line shows IQR.

FIGURE 7. Hour-by-hour plots (from midnight to midnight) of average smartphone use* in minutes, split by age group

15 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

However, they also expressed that managing their smart-

phone takes work, and being without their phone can be

freeing:

I feel like we'd all feel a lot better if we were on it

less. Like, when I lost my phone … I didn't have a

phone for a week, and that week was amazing.

Although I couldn't... I had to use my friends'

phones to contact people if I needed to text

them. Just not having a phone, it takes this weight

off of you. It almost sets you free in a way.

—11th grader

When I'm doing work, I like putting my phone to

the side, and whenever I give myself breaks, I'll go

to my phone and check notifications.

—11th grader

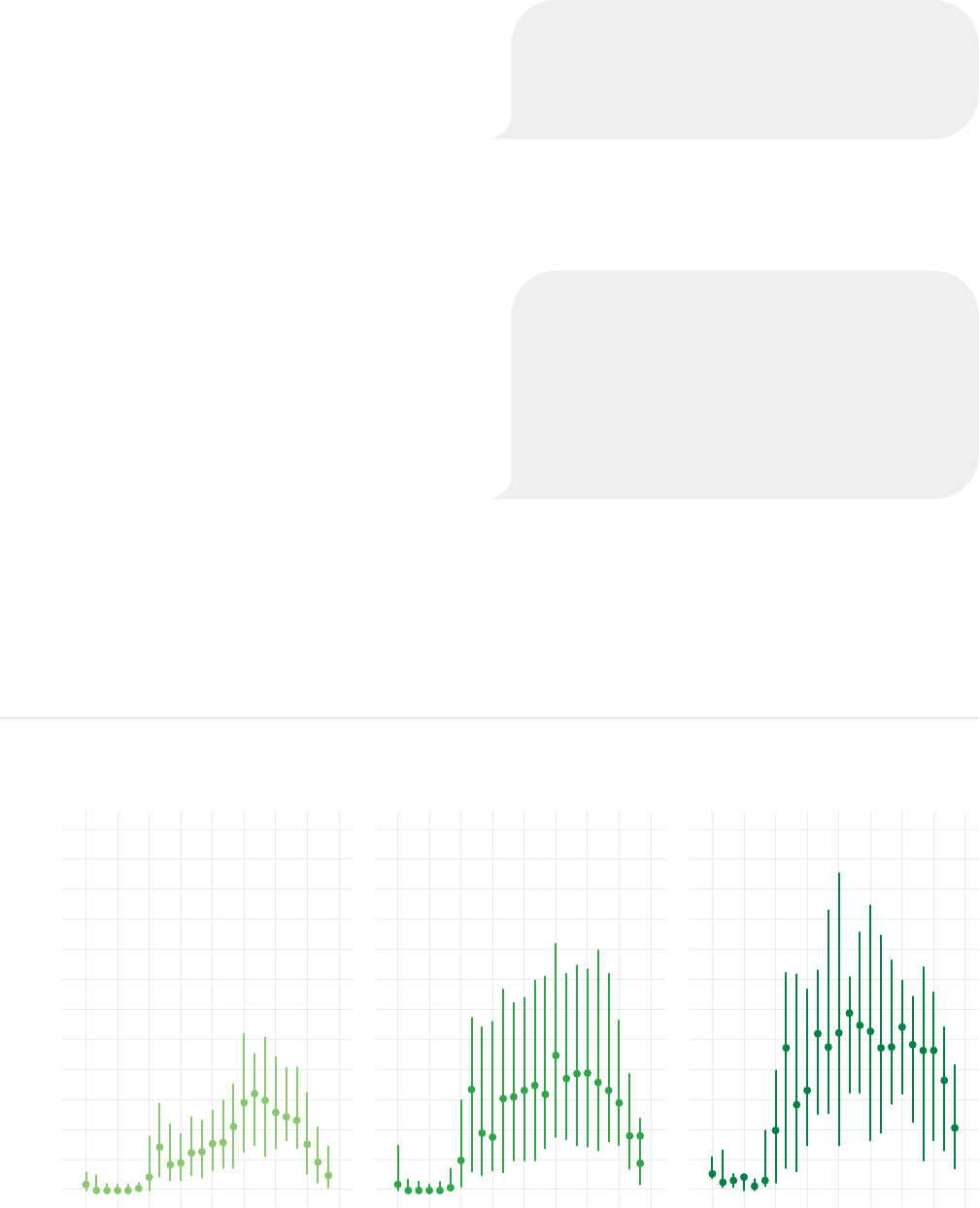

Participants picked up their phones a median of 51 times per

day, ranging from two to 498 times per day. When pickups

were graphed hour by hour (Figure 8), it was apparent that

teens (age 13 to 17) check their phone regularly through the

middle of the day (i.e., during school hours) as well as after

school. Younger participants (age 11 to 12) had the lowest

frequency of pickups per hour. Our youth advisors thought

this was probably due to younger smartphone owners having

more phone restrictions and rules placed by their caregivers

as well as smaller social networks to keep in touch with.

Time spent on smartphones varies widely.

Youth advisors were also intrigued by the extreme ends of

smartphone usage found in our study sample. While most

agreed that five hours per day seemed like the amount of time

most of their peers spend on their phone, they were surprised

that some 11- to 17-year-olds would use phones for only a few

minutes per day, or up to 16 hours/day. The daily usage pat-

terns of five participants with the lowest-duration usage, and

five with the most pervasive usage, are shown in Figures 9 and 10.

When talking about how much time their phone use takes up

in a day, most youth advisors felt that their phone integrates

into their daily experience in a non-burdensome way, and

provides small amounts of pleasure or social connection while

they do other things.

Average Pickups (median [IQR])

2

4

6

8

10

12

0

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am 12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am 12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

Time of Day

16-1713-1511−12

*Median is the value that 50% of the users are under and 50% are over. IQR is the Interquartile Range, which is the middle 50% of users, with 25% of users under the first value

and 25% of users over the second value. Dot shows the median value; line shows IQR.

FIGURE 8. Hour-by-hour plots (from midnight to midnight) of average smartphone pickups*, split by age group

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 16© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TAKEAWAYS

For most adolescents, smartphones take up a large

proportion of their waking hours. Whether this feels

like time well spent depends upon what they're expe-

riencing, what the smartphone is augmenting vs.

interrupting, and the other positive activities the

person had access to that day.

It's important to remember that smartphones are

going to be in both the background and the foreground

of kids' minds.

Young people's phone use patterns vary significantly

from each other, and the unique way that smartphones

interweave into a young person's day feels personal.

Many kids have a signature or pattern to their phone

use, their main "thing" that they love doing (or feel

obsessed with) on their phone, so it's worth helping

them reflect on how their particular personality influ-

ences their relationship with their phone.

TALKING POINTS

Adults can ask:

• What is your favorite app? Do you feel stressed

or excited by it? Or both?

• Does it feel like a job or "work" to stay up to date

on everything?

• What does it feel like when your phone is

commanding your attention vs. just being in

the background of your mind?

• What does it feel like when you don't have your

phone or the room is too quiet? Are you worried

about missing out on anything?

• Have you ever noticed what you're thinking

about if there's no background noise on?

• Do you ever get a sense that you've been on your

phone too long? What are the signs for you?

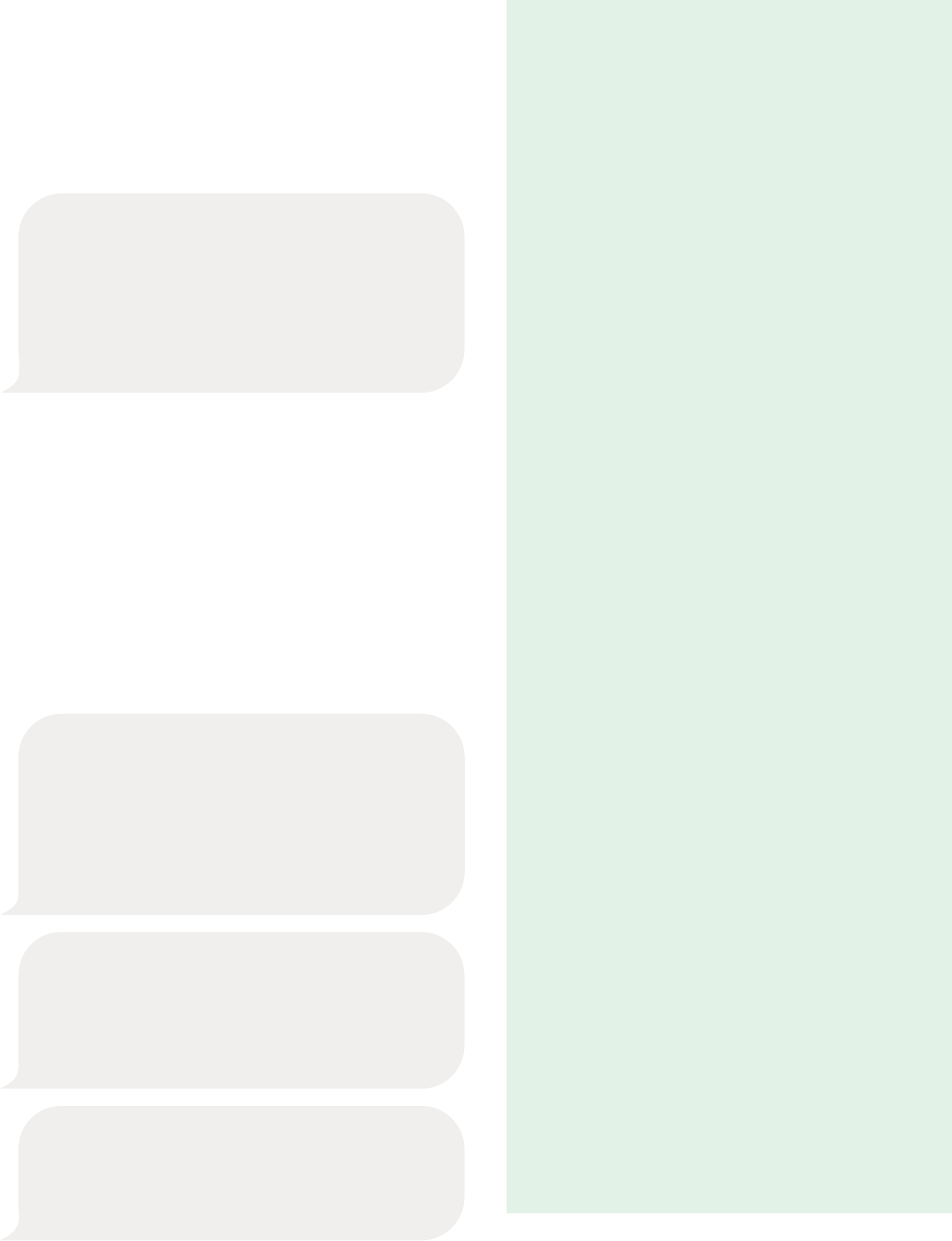

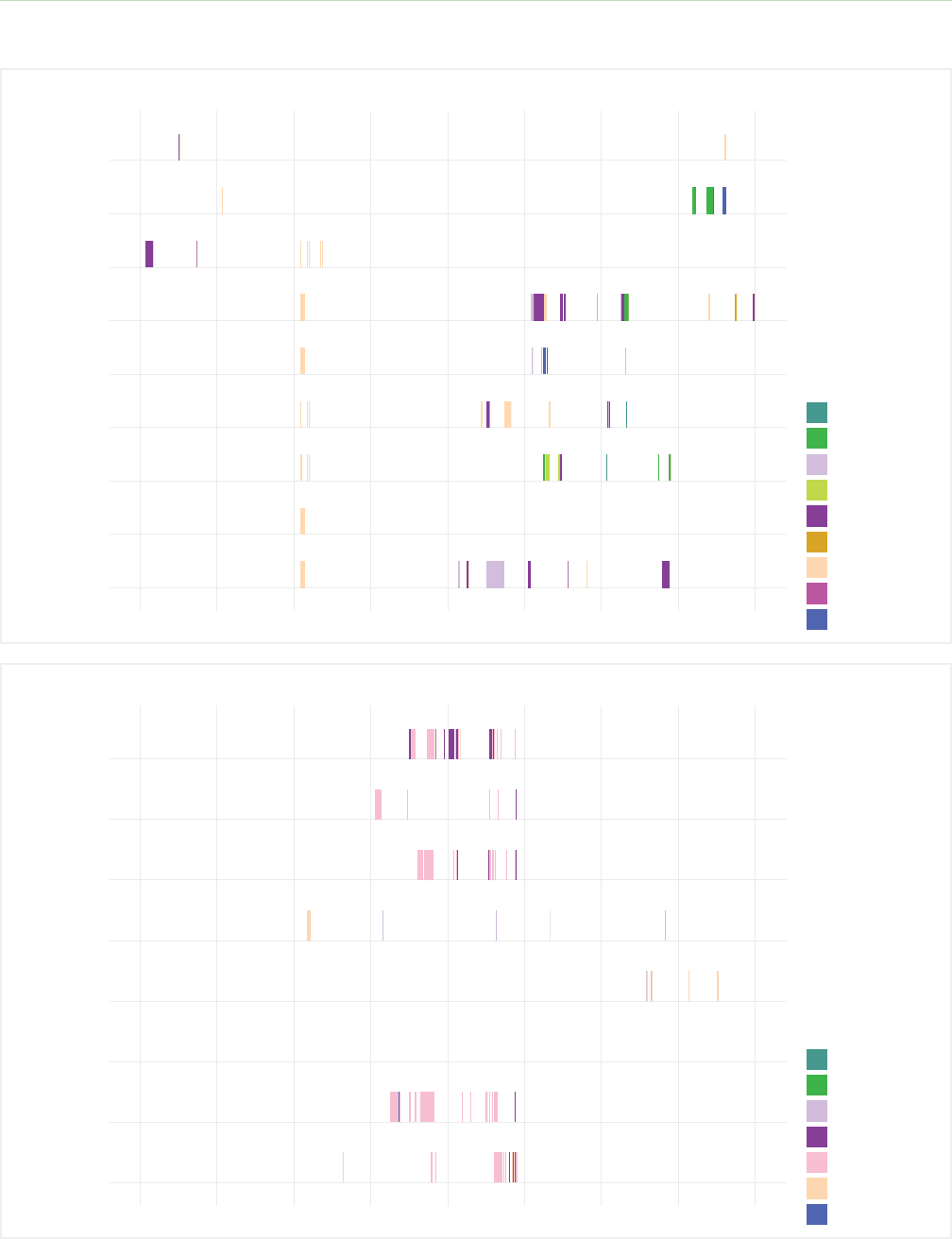

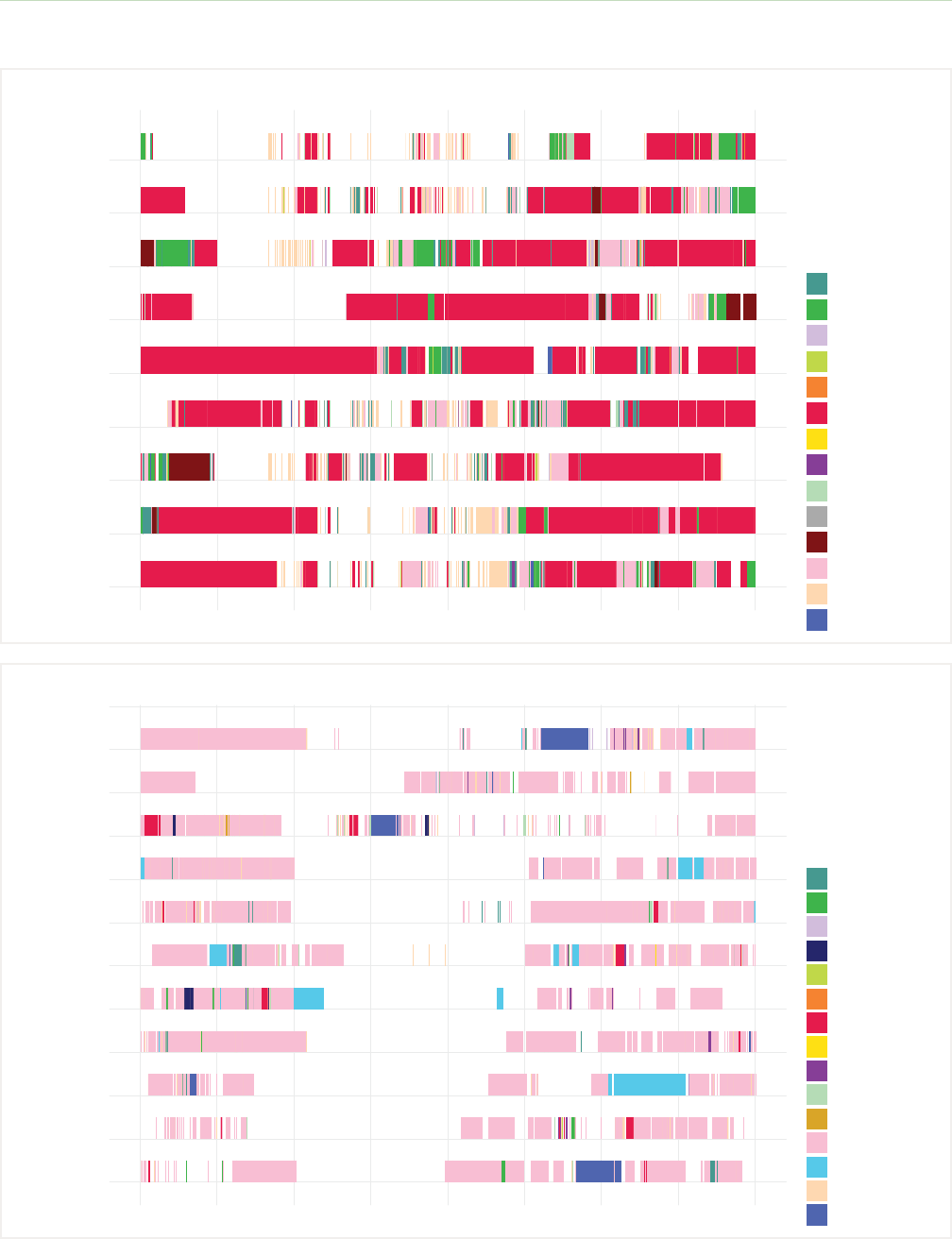

The adolescents we talked to also reflected on the fact that,

when looking at phone usage visualizations, it seemed that

each participant had their own "style" of use—their "thing"

that they tended to do more than any other activity on their

phone, such as social media (shown as pink shading; Figure 11),

mobile games (red shading; Figure 12), or YouTube (royal blue

shading; Figure 13).

Not all smartphone use is active; some is

background noise.

Youth advisors emphasized that it's important not to assume

that all usage appearing on participants' day-to-day visualiza-

tions was active smartphone usage. They described use of

phones as "background noise"—for example, streaming

movies or videos or music—while doing other activities. This

ambient use of smartphones in the background was described

as having a "stimulation" or calming purpose, in contrast to

engaged usage, such as texting with a friend, that "you can't

just blur out" into the background.

It seems like everybody has their own thing that

they're obsessed with. Like this person has

reading, versus another person has some sort of

YouTube. And it's different for each person, but

everybody seems to be using one thing as a

means to stay connected or to spend time.

—12th grader

Like I see kids in school literally just have

TikTok on autoplay while they're doing work,

like it's sitting on their desk, but they're not even

looking at it. It's just like to have some sort of

stimulation in their brain, I guess, while they're

doing something.

—10th grader

I know a lot of people who work with

Netflix playing. They'll just have it playing

either on their phone or on their computer,

or they'll sleep to it.

—11th grader

I definitely do that. Like if I'm doing laundry, if I'm

doing homework, I'll just have something so that

my room isn't quiet. I kind of enjoy that buzz.

—12th grader

17 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

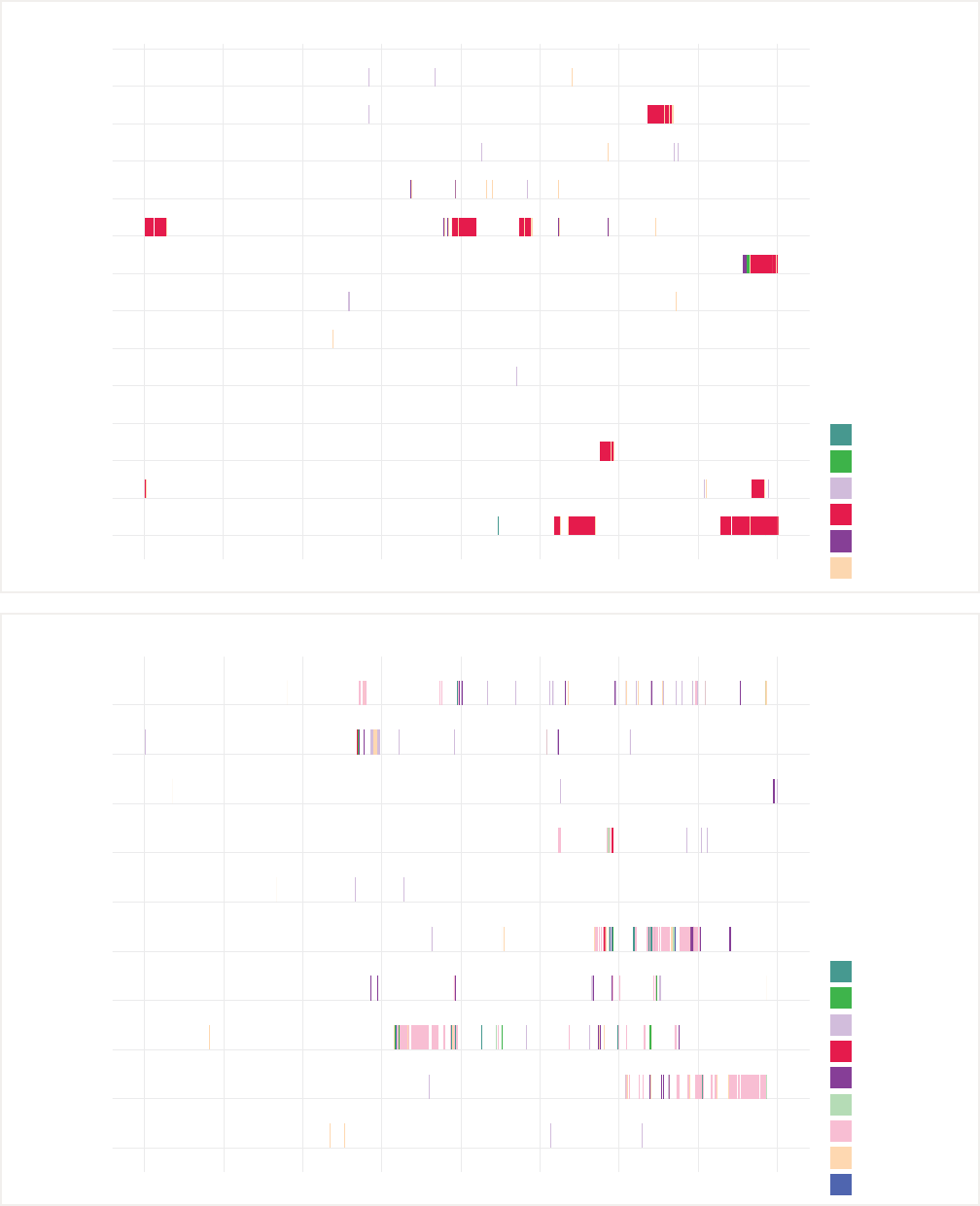

FIGURE 9. Participants with light smartphone usage

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Messaging

Social Media

Tools

YouTube

2022−10−06

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

13-year-old male

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Email

Messaging

Shopping

Tools

Video Chat

YouTube

13-year-old male

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 18© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Gaming

Messaging

Music and Audio

Tools

Social Media

YouTube

2022−10−06

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

13-year-old female

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Messaging

Gaming

Tools

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

2022−10−17

2022−10−18

2022−10−19

2022−10−20

2022−10−21

2022−10−22

2022−10−23

2022−10−24

2022−10−25

2022−10−26

2022−10−27

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

13-year-old female

19 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

FIGURE 10: Participants with longer daily duration of smartphone use

2022−08−27

2022−08−28

2022−08−29

2022−08−30

2022−08−31

2022−09−01

2022−09−02

2022−09−03

2022−09−04

2022−09−05

2022−09−06

2022−09−07

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Education

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Live Gaming

Music and Audio

Messaging

Shopping

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

YouTube

App Categories

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

11-year-old female

2022−11−08

2022−11−09

2022−11−10

2022−11−11

2022−11−12

2022−11−13

2022−11−14

2022−11−15

2022−11−16

App Categories

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Live Gaming

Music and Audio

Messaging

Parent Controls

Reading

Social Media

Tools

YouTube

17-year-old male

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 20© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

2022−10−17

2022−10−18

2022−10−19

2022−10−20

2022−10−21

2022−10−22

2022−10−23

2022−10−24

Art and Photos

App Categories

Browser

Calls

Education

Email

Gaming

Health and Fitness

Music and Audio

Messaging

Shopping

Social Media

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

14-year-old male

2022−10−05

2022−10−06

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

Art and Photos

App Categories

Browser

Calls

Email

Gaming

Music and Audio

Messaging

Reading

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

12-year-old female

21 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

FIGURE 11. Participants who primarily used social media apps

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

Art and Photos

App Categories

Browser

Calls

Education

Email

Music and Audio

Messaging

Parent Controls

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

Video Chat

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

14-year-old female

2022−09−29

2022−09−30

2022−10−01

2022−10−02

2022−10−03

2022−10−04

2022−10−05

2022−10−06

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

Art and Photos

App Categories

Browser

Calls

Education

Email

Gaming

Health and Fitness

Music and Audio

Messaging

Parent Controls

Shopping

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

16-year-old female

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 22© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

2022−09−02

2022−09−03

2022−09−04

2022−09−05

2022−09−06

2022−09−07

2022−09−08

2022−09−09

2022−09−10

2022−09−11

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Education

Email

Gaming

Messaging

Social Media

Tools

Art and Photos

App Categories

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

15-year-old female

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

2022−10−17

2022−10−18

2022−10−19

2022−10−20

Art and Photos

App Categories

Browser

Email

Gaming

Music and Audio

Messaging

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

12-year-old male

23 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

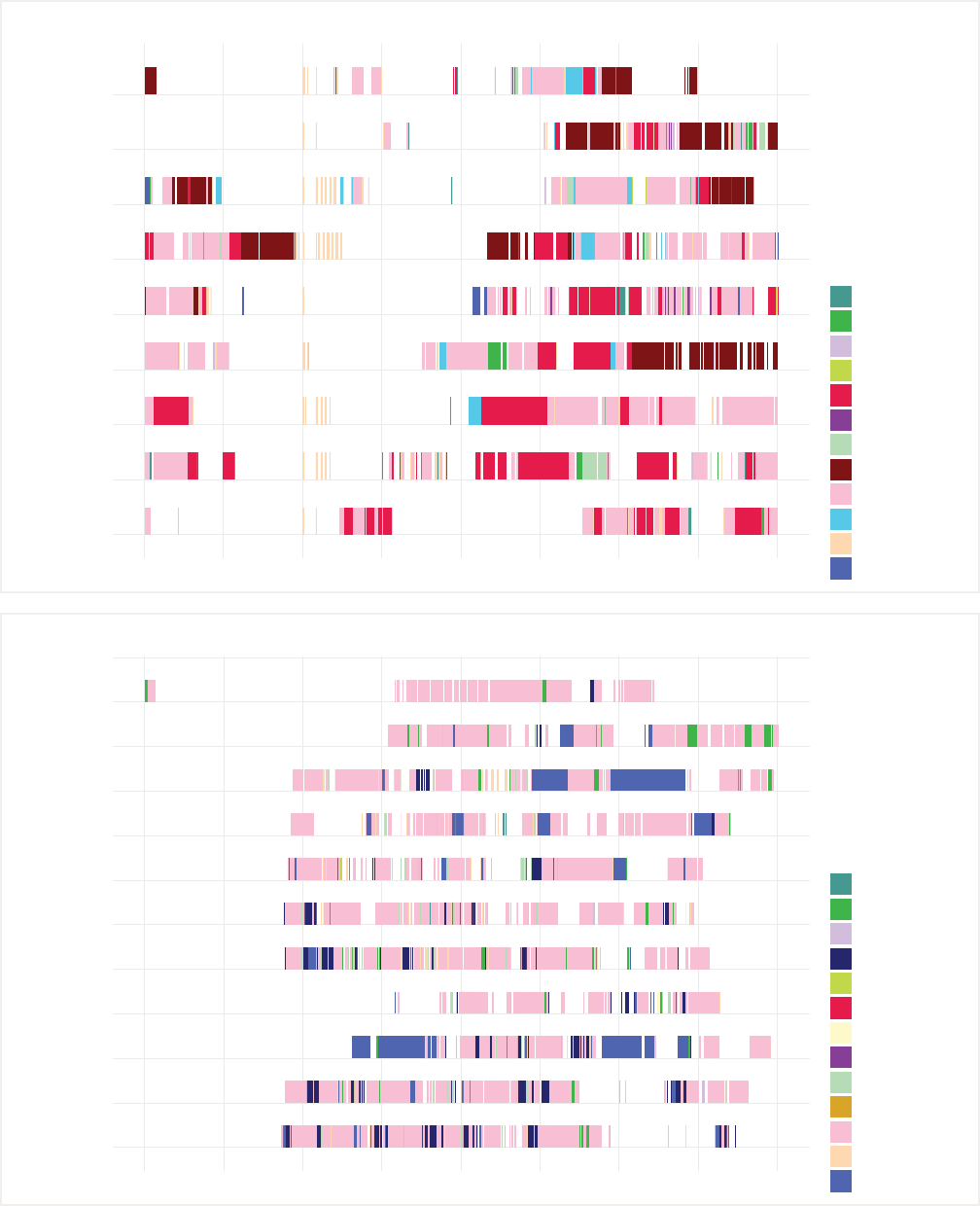

FIGURE 12: Participants who primarily used mobile games

2022−08−31

2022−09−01

2022−09−02

2022−09−03

2022−09−04

2022−09−05

2022−09−06

2022−09−07

App Categories

Browser

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Messaging

Social Media

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

11-year-old male

2022−11−12

2022−11−13

2022−11−14

2022−11−15

2022−11−16

2022−11−17

2022−11−18

2022−11−19

2022−11−20

Browser

App Categories

Calls

Gaming

Messaging

Reading

Tools

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

11-year-old male

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 24© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Art and Photos

App Categories

Browser

Calls

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Messaging

Shopping

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

Video Chat

YouTube

2022−09−30

2022−10−01

2022−10−02

2022−10−03

2022−10−04

2022−10−05

2022−10−06

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

14-year-old female

2022−11−01

2022−11−02

2022−11−03

2022−11−04

2022−11−05

2022−11−06

2022−11−07

2022−11−08

2022−11−09

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Gaming

Messaging

Social Media

Tools

YouTube

App Categories

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

11-year-old male

25 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

FIGURE 13: Participants who primarily used YouTube apps

2022−08−26

2022−08−27

2022−08−28

2022−08−29

2022−08−30

2022−08−31

2022−09−01

2022−09−02

2022−09−03

2022−09−04

2022−09−05

2022−09−06

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Education

Email

Gaming

Music and Audio

Messaging

Tools

Video Chat

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

12-year-old female

2022−11−09

2022−11−10

2022−11−11

2022−11−12

2022−11−13

2022−11−14

2022−11−15

2022−11−16

2022−11−17

2022−11−18

2022−11−19

2022−11−20

2022−11−21

2022−11−22

2022−11−23

2022−11−24

2022−11−25

2022−11−26

2022−11−27

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Health and Fitness

Music and Audio

Messaging

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

11-year-old female

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 26© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

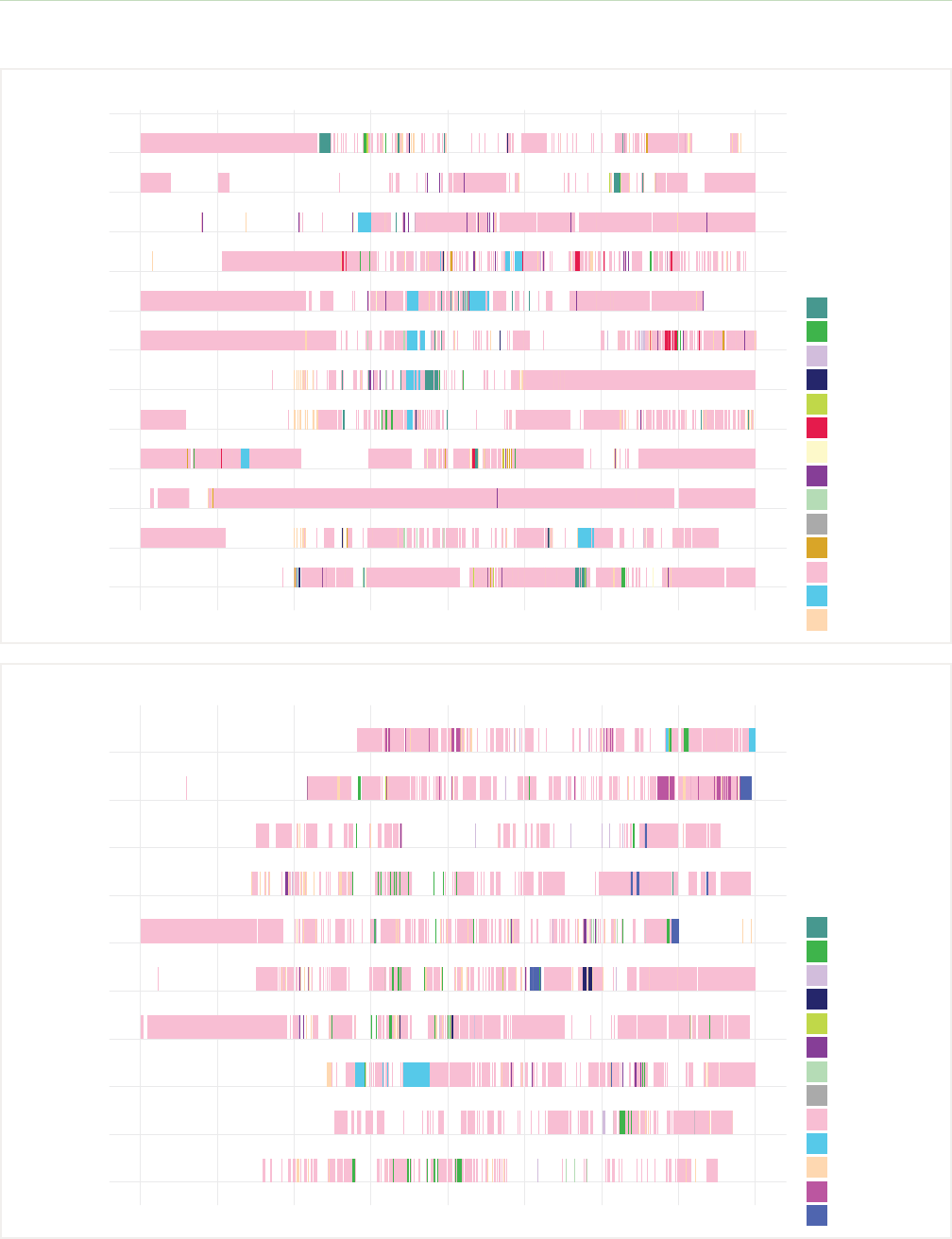

2022−10−06

2022−10−07

2022−10−08

2022−10−09

2022−10−10

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

2022−10−17

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Music and Audio

Messaging

Social Media

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

15-year-old female

2022−10−11

2022−10−12

2022−10−13

2022−10−14

2022−10−15

2022−10−16

2022−10−17

2022−10−18

2022−10−19

App Categories

Art and Photos

Browser

Calls

Entertainment

Email

Gaming

Messaging

Social Media

Streaming Video

Tools

YouTube

12am 6am 12pm 6pm 12am

16-year-old male

27 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

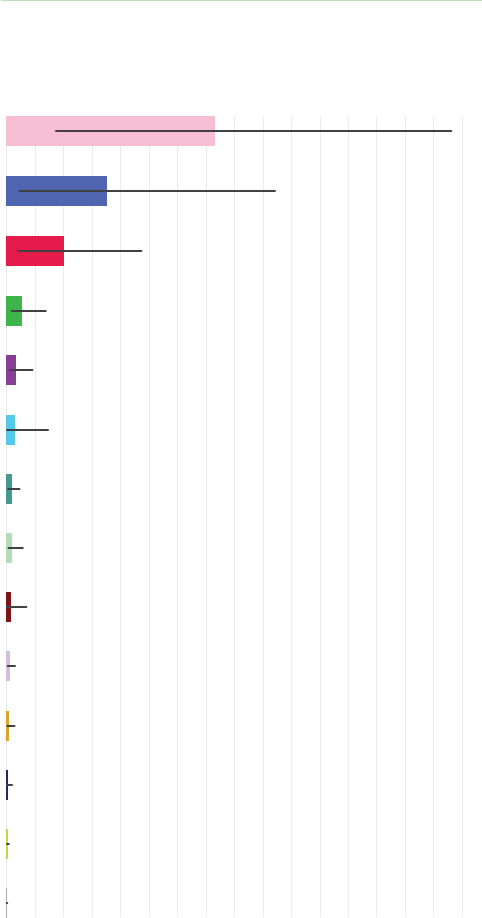

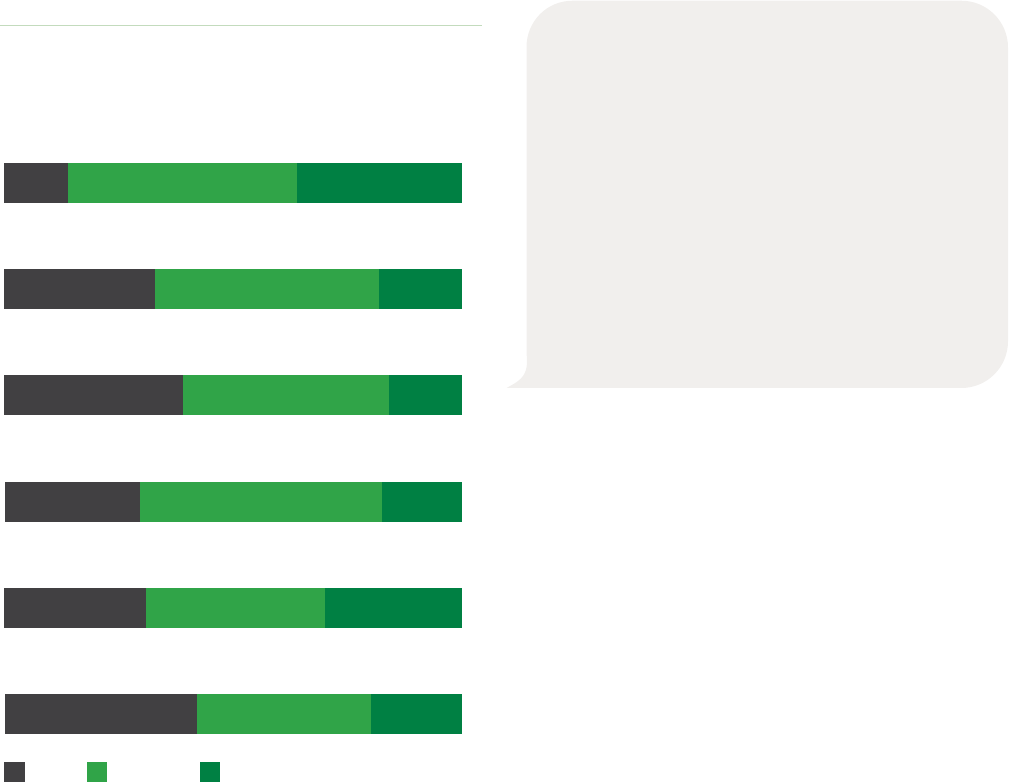

FIGURE 14. Median and IQR* of daily duration of different

app categories**, ranked from longest to shortest duration

*Median is the value that 50% of the users are under and 50% are over. IQR is the

Interquartile Range, which is the middle 50% of users, with 25% of users under the

first value and 25% of users over the second value. Bar shows the median value;

black line shows IQR.

**Includes only participants who used that category of apps.

Which types of apps did participants

use the longest, and why?

While time is often held out as the most important measure of

how young people use their screen-based devices, time is only

one dimension of the smartphone experience. What young

people do, the content they view and the interactions they

have on their smartphones are critical components of how

they use their devices. Research shows that the quality of the

content and types of activities youth engage with online are

more strongly associated with well-being (Popat & Tarrant,

2023). For example, creative and positive social uses of media

are associated with higher well-being, while viewing more

violent or toxic content is linked with more distress. And while

our methodology cannot tell us exactly what content youth

saw on their phones, understanding what types of apps are

used and in what duration gives us a framework to begin to

understand youths' exposure to different types of content.

The 203 participants in our sample used a total of 1,644

unique apps over the week that their smartphones were

tracked. Individual participants used anywhere from five to

125 different apps over the course of the week, averaging

about 40 different apps overall.

When we looked at categories of apps, social media apps were

used for the longest each day, on average, followed by

YouTube (which includes YouTube, YouTube Kids, and YouTube

TV), mobile games, browser, messaging, and streaming video

(see Figure 14). When considered as a proportion of a partici-

pant's overall smartphone usage, social media (42%), YouTube

(19%), and gaming (11%) apps took up the largest percentage

of time per day, among participants who used those apps. In

contrast, despite their popularity, photography/camera apps,

phone calls, and music apps were only used for a few minutes

per day.

Parent Controls (n=48)

Email (n=146)

Education (n=75)

Shopping (n=79)

Calls (n=181)

Reading (n=44)

Music and Audio (n=144)

Art and Photos (n=192)

Streaming Video (n=93)

Messaging (n=193)

Browser (n=200)

Gaming (n=178)

YouTube (n=177)

Social Media (n=153)

Average Daily Minutes (Median [IQR])

75 100 125 150 175 20050250

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 28© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Younger participants had the longest duration of the gaming

category of apps. One youth advisor explained the change in

smartphone habits by age this way:

Definitely with more mature teenage audiences,

I feel like there's less game usage ... but I think it

also kind of just depends on who the phone user

is. But I also think that it can be a mix of both.

Like you said, we kind of all get drawn to our

phones when we don't have anything to do, and

definitely I think that social media has kind of

replaced games for older audiences, because it's

like you can pick it up and it's quick entertain-

ment, which is kind of like what a game is, it's

interactive quick entertainment.

—9th grader

This used to apply to me. I'm not active on it

anymore. But the game Hay Day is kind of ... it's

one of the games where you have to come back at

certain intervals to maintain your farm. So I can

see that, like waking up at 8 a.m. and coming back

to it consistently every day, just being integrated

into your schedule because that's how a lot of

people are with it. They know that whenever they

wake up, oh, there's new things to check, you

have to go and maintain your farm, and it's just

like part of their everyday lives.

—11th grader

Over the study week, 657 different mobile games were played

overall, of which 211 (32%) had violent content ratings. When

looking at the mobile gaming patterns found in our partici-

pants, youth advisors found it interesting that some gaming

took place at seemingly random times of day. This was

explained by the fact that some games send notifications to

re-engage the player every day, while other games are

designed in ways that expect frequent engagement to main-

tain progress in the game:

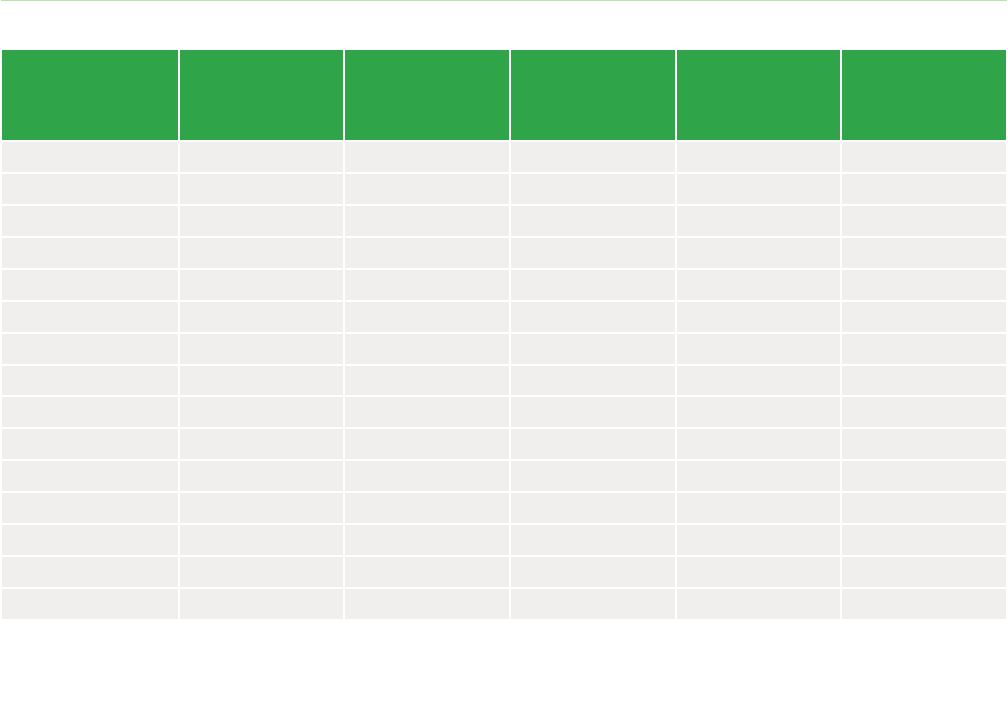

TABLE 2. Popular apps, their number of users, average daily duration, and percentage of total smartphone use they

composed on a typical day*

App name N (%) users

Average daily duration

Median [IQR]**

Range

(hour:minutes)

Percentage of daily use

(median)***

TikTok 102 (50.2%) 1:52 [0:24 - 2:57] <0:01 - 7:48 38.4%

YouTube 175 (86.2%) 0:40 [0:05 - 1:52] <0:01 - 10:13 18.2%

Instagram 70 (34.5%) 0:16 [0:03 - 0:52] <0:01 - 2:56 5.9%

Snapchat 79 (38.9%) 0:10 [0:02 - 0:36] <0:01 - 3:13 3.6%

Discord 72 (35.5%) 0:07 [0:02 - 0:24] <0:01 - 12:20 2.5%

Roblox 74 (36.5%) 0:06 [0:01 - 0:40] <0:01 - 6:25 2.6%

Chrome 191 (94.1%) 0:04 [0:01 - 0:13] <0:01 - 1:24 1.5%

Netflix 53 (26.1%) 0:03 [0:01 - 0:17] <0:01 - 7:31 0.8%

Spotify 81 (39.9%) 0:01 [<0:01 - 0:04] <0:01 - 0:31 0.6%

Facebook 40 (19.7%) 0:01 [<0:01 - 0:04] <0:01 - 1:34 0.1%

Google quick

search box

180 (88.7%) 0:01 [<0:01 - 0:03] <0:01 - 0:21 0.6%

Amazon 47 (23.2%) 0:01 [<0:01 - 0:03] <0:01 - 0:20 0.3%

Pinterest 36 (17.7%) 0:01 [<0:01 - 0:03] <0:01 - 0:48 0.4%

*Calculated only among participants who used that app.

**Median is the value that 50% of the users are under and 50% are over. IQR is the Interquartile Range, which is the middle 50% of users, with 25% of users under the first

value and 25% of users over the second value.

***Percentage of daily use is calculated among those who use the app and as a percentage of all their smartphone use in a day.

29 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

I'd say compared to YouTube, [TikTok] is that you

don't have to search through to find a video that

you wanna watch ... I mean if you're on the

Explorer tab for Instagram, or for YouTube, you

have to kind of decide, but it does it for you. So

you can open the app and instantly have a video

you'll probably like.

—10th grader

It's just you watch a video and it's interesting and

you scroll and it's another interesting video. You

don't even have to find videos on your own, it's

right there, it's customized, and you can share

funny things with your friends, so it's addicting.

—12th grader

TikTok: Teens talk about the ease and capture of

the endless short video scroll

When we asked the youth advisors why their peers scrolled

TikTok for nearly two hours a day, taking up almost 40% of

their total phone time, they had lots to say! While text-based

platforms like Twitter are "more work," TikTok was described

as "so easy" because users can simply open up the app and

videos start to play endlessly, compared to having to "actively"

click on videos. Discussing TikTok, two youth advisors shared:

Apps that dominate time: TikTok and YouTube

Some of the most popular apps used by 11- to 17-year-olds in

our sample are shown in Table 2. Of these, those with the

longest daily duration were TikTok, YouTube, Instagram,

Snapchat, Discord, Roblox, Chrome, and Netflix. (Of note,

although Spotify usually streams music for long periods of

time, it is not recorded by our study app as 'in use' because the

screen is usually off while music streams).

Figure 15 shows the distribution of daily duration of use of the

longest-running popular apps in our sample. TikTok and

YouTube had far more users who spent several hours per day

using these apps, with 64% spending more than an hour/day

on TikTok, and 41% doing the same on YouTube. Our youth

advisors attributed this finding to video length, the friction-

less features of these platforms, and the algorithmic tailoring

of videos to a users' interests, making it difficult to disengage.

In contrast, 22% of Snapchat and 7% of Discord users aver-

aged more than one hour/day on these platforms, which youth

advisors noted are primarily for chatting with friends, so they

are used for briefer snippets of time.

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 30© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

FIGURE 15. Average daily duration of select popular apps

TikTok (n=102)

5%

10%

22%

20%

10%

5%

22%

8%

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

15-30 min

0-15 min

>5 hours

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

15-30 min

0-15 min

>5 hours

0%

0%

Discord (n=72)

1%

1%

12%

17%

64%

4%

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

15-30 min

0-15 min

>5 hours

YouTube (n=175)

3%

6%

10%

17%

14%

10%

34%

5%

0%

0%

Snapchat (n=79)

1%

5%

15%

5%

10%

63%

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

15-30 min

0-15 min

>5 hours

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

15-30 min

0-15 min

>5 hours

Instagram (n=70)

0%

0%

11%

11%

17%

11%

49%

0%

4-5 hours

3-4 hours

2-3 hours

1-2 hours

30-60 min

15-30 min

0-15 min

>5 hours

0%

0%

Roblox (n=74)

1%

15%

12%

5%

64%

3%

31 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Another key piece of TikTok's appeal to teens was that it could

be consumed in small bites of time, such as in between classes,

compared to more "time-consuming" platforms that need a

time or mental investment, such as YouTube or Netflix. They

also noted with TikTok how quickly the algorithm can learn

what they want and shift to meet their current needs.

A lot of people I know are actually defaulting

more to TikTok and social media sites where they

can get kind of like the quick hit of just like a

short video. So I was surprised that some people

spent that much time on YouTube 'cause most

people I know, if they wanna watch video

content, then they'll go to TikTok. You can easily

just scroll past it. But then also, they're just so

short that even if you're not necessarily that

interested, watching it won't really take up that

much time anyway.

—10th grader

Something that usually breaks that chain of

scrolling on Twitter is … I'll see a tweet that I've

already seen before, so I'm like, 'OK, time for

me to get off.' Whereas TikTok there's nothing to

really break that chain of constant new

information and the stimulation … But TikTok

is definitely more of an internal struggle to

actually be like, 'let me get off,' simply 'cause

the content is just so easy to consume, so it just

feels like an urge to continue to keep scrolling.

—11th grader

TikTok is one of the worst forms of it because it's

not much work, you're just scrolling, and also, you

keep on scrolling and you're finding maybe these

things interesting because your feed is accustomed

to you. And it's easy, it's quick, and I feel like that's

also why a lot of our attention spans are getting

much shorter, because even sometimes ... I'm not

on TikTok as much as I used to be, but when I was

really on it, I would find myself skipping videos

that were over 30 seconds because I couldn't ... I

just wanted to keep on scrolling, keep on scrolling.

—11th grader

Automatic advancement of content feeds also contributed to

the "overflowing" experience of using TikTok or YouTube, and

the challenges some teens feel in breaking away from the feed

of videos:

You have to have a bunch of ideas and a bunch of

different videos flowing into your mind and just

that constant flow of information just overflow-

ing, kind of being overwhelming, I feel like, to an

extent. And I feel like for Netflix, though, it's

helpful and it's better in terms of splitting up the

movies you watch because there's that like ... It's

like start the new episode, and then you kinda get

that guilt like, 'Oh, should I start this whole new

episode and waste another 20 minutes, or should

I just go start my homework?' So I feel like that's

why TikTok is so much more time-consuming, and

YouTube as well, because it just never stops.

There's no end… so they all just, I would say, inev-

itably just keep going on and just blend together.

—10th grader

Youth advisors also mentioned how design features like lack

of friction, infinite content, and the short video format influ-

enced their behavior on TikTok:

CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE 32© COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Personally, I have one on my TikTok for 45

minutes, but there definitely are some days where

I see it and it's like, 'You have five minutes left for

the day for TikTok,' and I'm like, 'I don't care,' and

I just ignore it. [chuckle] So I think it depends on

how I'm feeling in the day, 'cause sometimes I do

follow that guideline or that restriction, but

sometimes I don't.

—11th grader

I think that most teens don't really follow it, espe-

cially if they set it themselves. It has to be

parent-enforced with a passcode or whatever for

teens to actually follow it. But I feel like, in my

experience, for TikTok, I'm spending two or three

hours a day on TikTok. And I'll set these restric-

tions, yet I'll just block it every time I see it. So I

find it annoying after a while, but I think it's

helpful once I get the notification over and over

to realize that I'm really just wasting my time.

—10th grader

But I also know that YouTube has a sleep notifica-

tion. Like sometimes I get, 'It's time for bed,' and

then you could dismiss it or continue on the app.

—11th grader

We asked youth advisors whether they had tried out time limit

features on TikTok or YouTube, and some had—with mixed

success:

TAKEAWAYS

Time on smartphones among young people is domi-

nated by apps that provide social interaction,

entertaining videos, and games—many of which have

design features that encourage prolonged engage-

ment. These include finely tuned algorithms that can

even adapt to how a child or teen is feeling in the

moment, infinite scrolling of content made by creators

who are competing for attention, and "frictionless"

navigation. (In contrast, a design feature that adds fric-

tion would slow down navigation, cause the user to

pause and make a decision, let them know that they

are "caught up," or encourage them to take a break.)

TikTok in particular was described by our youth advi-

sors as having a lot of engaging ingredients as well as

an ability to be consumed in bite-size bits during down-

time or in between classes. In contrast, apps that

young people use for goal-oriented purposes (such as

taking photos, shopping, or looking something up on a

browser) commanded much less time. Caregivers

should be sensitive to the fact that the companies who

build apps have incentives to design features that

capture kids' attention for longer (such as wanting

more advertising revenue or data collected for tar-

geted marketing), and it's not just kids' lack of

"willpower" that keeps them on their phones.

TALKING POINTS

Adults can ask:

• Which apps take up most of your time (and my

own time, as a parent)? Why is this?

• Are there design features that make your favorite

app hard to put down?

• What do you think social media platforms know

about us, in terms of who we are and how we are

feeling? How do algorithms predict what we

might want to watch or follow?

• How do you see the platform's algorithms at

work? Have you noticed when it's working to

keep you on the app, and how it does that?

• What are some ways to be "in the driver's seat"

while using your phone, other than timers that

don't always work? Are there ways to be con-

scious of the need to not use your phone at

certain times of day? Are there places that you

could keep your phone, some apps that you could

remove, or "do not disturb" settings that could

help you feel more in control?

33 CONSTANT COMPANION: A WEEK IN THE LIFE OF A YOUNG PERSON'S SMARTPHONE USE © COMMON SENSE MEDIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

App stores have age ratings that

recommend how old the users of

specic apps should be, but these are

not routinely enforced. Age-restricting

"gates" on apps and app stores, such

as entering a birth date, have always

been easy to get through. This means

that it is easy for young smartphone

users to wade (or intentionally jump)

into territory that was not intended

for them. Therefore, we explored

whether our participants appeared

to be accessing age-inappropriate

apps on their smartphones.

NSFK? What we found about participants

using apps intended for older audiences

Under-13s regularly use social media and

age-inappropriate apps

Of 85 participants who were younger than 13, 68% used

social media apps, and they all used at least one app rated